By Michael Middleton and Dr. Sacoby Wilson

The writers are, respectively, executive director of the SB7 Coalition in South Baltimore and the director of the Center for Community Engagement, Environmental Justice, and Health at the Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health.

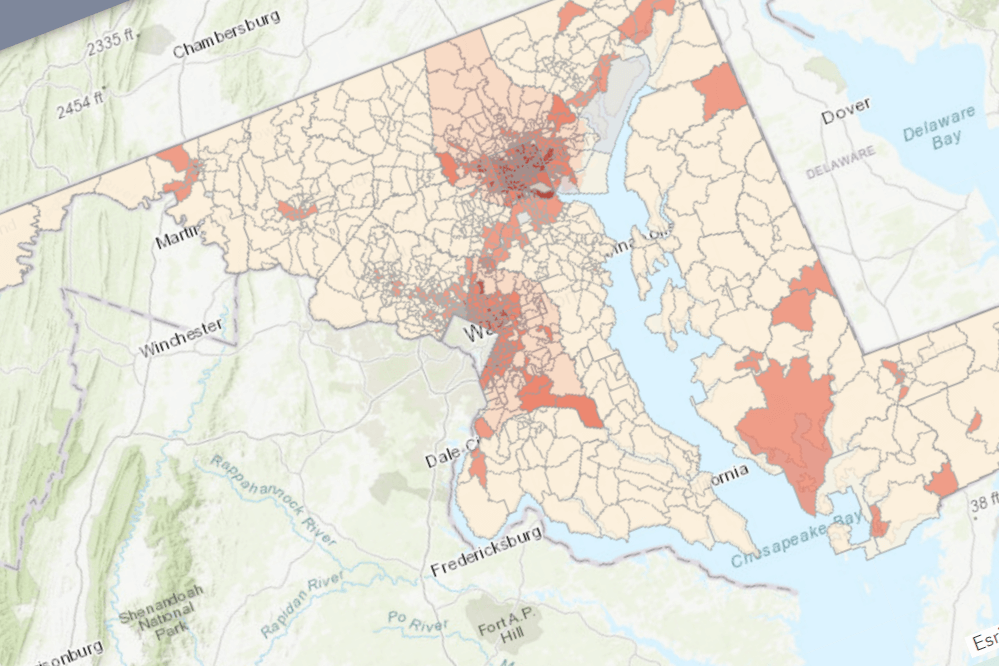

South Baltimore is a sacrifice zone. The six communities that make up South Baltimore — Cherry Hill, Westport, Mt. Winans, Lakeland, Brooklyn, and Curtis Bay — rank in the top 3% of the state for environmental burden using a Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) screening tool.

Curtis Bay, the highest in the state, is Maryland’s poster child for environmental injustice. Industrial areas near Curtis Bay house oil tanks, a wastewater treatment plant, chemical plants, landfills, the country’s largest medical waste incinerator, and more. Heavy diesel trucks frequent residential streets. The Wagner’s Point and Fairfield communities that were once Curtis Bay’s neighbors to the east are gone. Those residents accepted buyouts to leave between the 1980s and 2011 after a series of chemical spills and accidents.

Given Curtis Bay’s pollution burden, local activists expected, when MDE began supporting an “environmental justice” bill, that their concerns would be prioritized if not fully addressed. The environmental justice movement has long recognized affected communities’ right to self-determination as a key principle. MDE held a listening session in Curtis Bay in 2023 for residents to share their concerns, which made it seem likely that the agency’s bill would be responsive.

But that is not what happened. Instead of prioritizing problems identified by Maryland’s hardest-hit communities, MDE went a different way. The agency’s bill allows MDE to use pollution burden to influence decisions for a list of permits, which has been in Maryland law for over 30 years, with only one change during that time. More troubling, the list largely excludes air pollution permits, one of the top concerns for Curtis Bay residents.

And it’s not just a few air pollution permits that are uncovered by the bill. The bill does not cover any permit to operate an already-existing air pollution source, no matter how large or dirty. Not the trash incinerator in Westport, four miles north of Curtis Bay. Not the two large coal plants four miles south of Curtis Bay or the nearby medical waste incinerator. And certainly not the massive coal export terminal that sits near homes in Curtis Bay, which residents have been asking the state to address for over a decade.

The bill also does not cover air permits for some of the largest newly-built sources. Permits to build energy generators, like power plants and electricity-producing incinerators, are issued by the Maryland Public Service Commission. These permits are also not covered by the bill.

Some of Curtis Bay’s current activists were first spurred to speak out by a 2009 proposal to build the nation’s largest trash incinerator nearby. The multi-year fight against this proposal achieved success in 2016, along with international recognition when a Goldman Environmental Prize was awarded to one of the campaign’s leaders. But if the same incinerator were proposed now, the current bill would not address its air permit.

Is the current bill a step in the right direction and might the missing air pollution permits be added later? No. This bill would direct finite agency resources toward other types of permit decisions, ones less directly connected to the health of South Baltimore residents.

The bill covers just about every type of permit for discharges of pollution into surface waters and, given the strong influence of the Chesapeake Bay water-quality movement in Maryland, it’s likely that agency resources would go largely to these issues. Water quality matters but focusing on it over air quality is not in line with current science or practice related to addressing environmental justice in other states and cities.

Of the 21 pollution factors that MDE looks at when assessing which communities suffer most from environmental harms (called an “EJ Score” when combined with demographic data), about half relate solely to air pollution exposure. Only one relates solely to surface water pollution but the bill prioritizes surface water and not air quality. MDE is identifying communities overburdened mainly with air pollution but not trying to address the problem.

Legislators should not pass this bill (HB24/SB96). Instead, MDE should meet with residents of environmental justice communities to present options for what a bill for next year could look like.This should be a community-driven process with residents of the affected neighborhoods selecting the priorities addressed in the bill. And we should come back in 2025 to finish the job.

Maryland’s most overburdened communities badly need a real environmental justice bill with them in the driver’s seat and not mere observers.

The House bill is up for a hearing on Wednesday at 1 p.m. in the Environment and Transportation Committee. The Senate bill will be heard on March 5 in the Committee on Education, Energy and the Environment.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution