Advocates reimagine Red Line as a phased-in subway project

Activists in West Baltimore are proposing a phased-in plan that reinvents the Red Line light rail project.

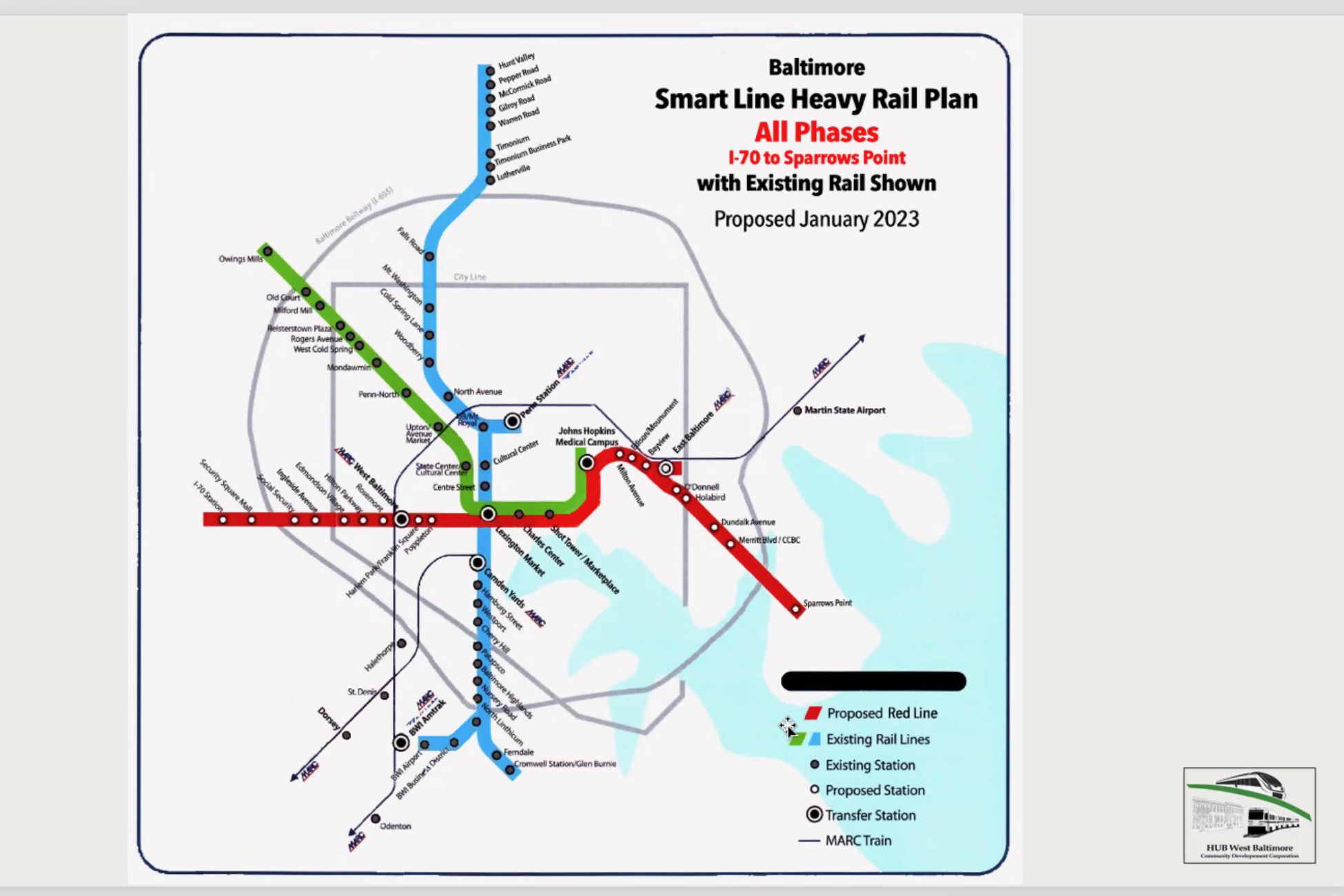

The Smart Line plan reimagines the now defunct project as a subway line, offering the ability to transport more people faster. Once built out, advocates said it could one day connect western Baltimore County to Sparrows Point in eastern Baltimore County.

Jonathan Sacks, executive director of HUB West Baltimore Community Development Corporation, said there is a knee jerk reaction against building subway lines because of the expense. Sacks presented the plan during a meeting Thursday organized by Baltimore-based Transit Choices.

“We think this is a really important proposal to consider and we hear reflexively all the time how expensive heavy rail is,” said Sacks. “When you say it to the folks…at the Maryland Department of Transportation, when you say to folks at the [Maryland Transit Administration], they say it’s too expensive, heavy rail is really expensive. Well, but is it, and is it less expensive than a $6 billion light rail, and can you do more if you do it in chunks.”

Sacks is part of a team that includes the Edmondson Community Organization that is proposing a reimagined vision for an east-west transit line. The proposal calls for a subway built in five phases. The line, once built out, would connect Sparrows Point to western Baltimore County and possibly reach as far as Interstate 70.

A proposal by Edmondson Community Organization and HUB West Baltimore Community Development Corporation envisions the new Red Line project as a subway line built in as many as five phases. Screenshot from Smart Line power point presentation.

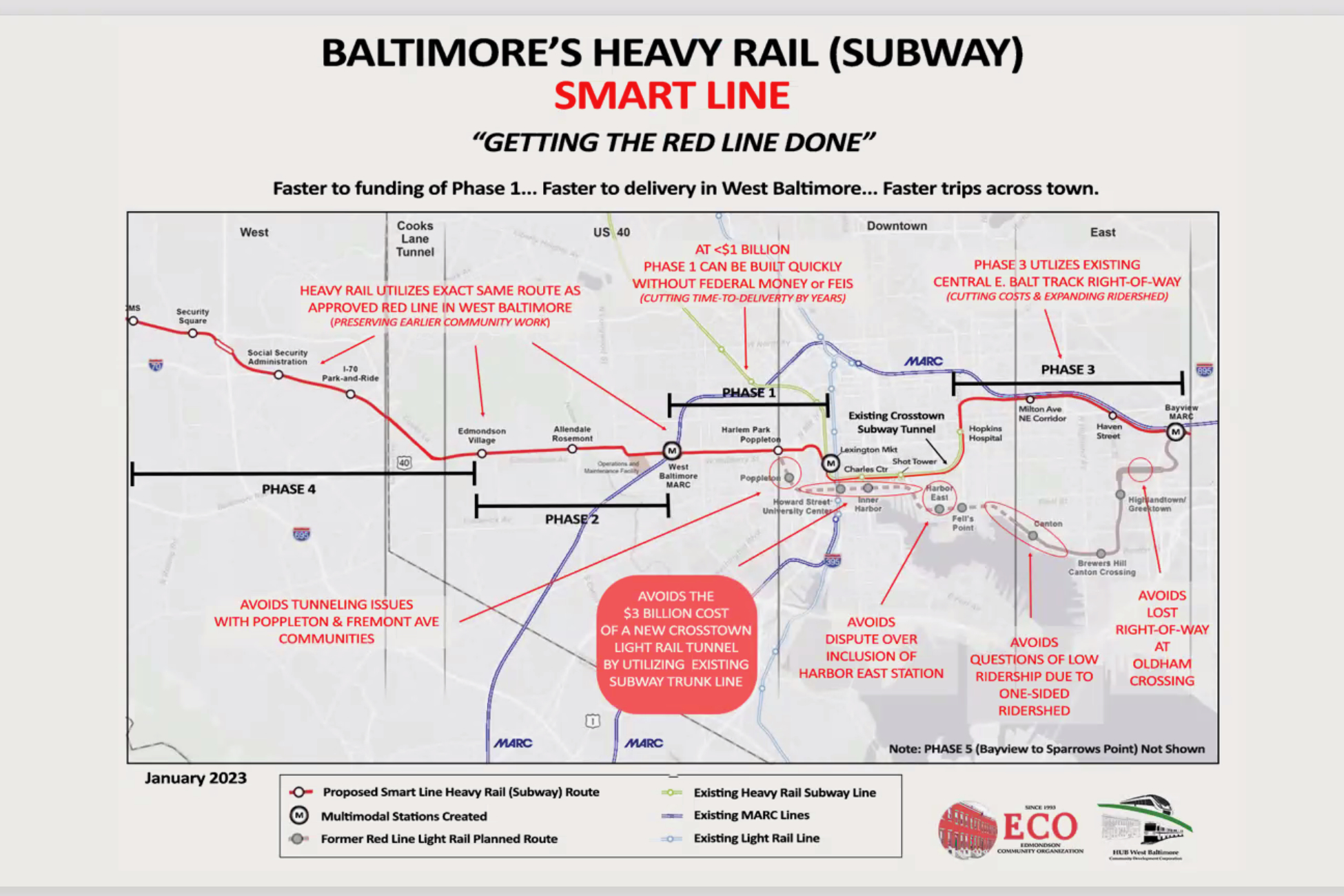

The initial phase of the plan would tie the West Baltimore MARC station to Johns Hopkins Hospital through Lexington Market. It would rely on using areas including the middle of the so-called “highway to nowhere” in West Baltimore as well as other properties already owned by Baltimore City. In addition to connecting to the existing subway tunnel at Lexington Market, the proposal calls for an additional half-mile of tunneling to complete the leg.

Sacks and other advocates said building the first leg could be done with state funding alone. Doing so without federal funds could allow a faster build, eliminate the need for a federal environmental study, and allow Gov. Wes Moore (D) to fulfill his promise to revive the Red Line project, if only the first portion.

Additional legs would be built heading east and later stretching into western Baltimore County. Breaking the project into five phases allows for “the opportune moments when you can get that next chunk of money because the chunks of money are swallowable enough that you can actually conceive of doing them,” Sacks said.

A subway would allow faster trips — as short as 30 minutes from West Baltimore to Sparrows Point.

The price tag remains elusive. Phase one and phase three — a leg that would extend east from Johns Hopkins Hospital to the East Baltimore MARC station — carry an estimated price tag of $1 billion. That price does not include the costs of revamping the MARC station into a modern, multimodal transportation hub.

Other legs that would extend further west include significant tunneling and have no initial estimates from the group.

“That’s still a lot of money,” said John Hillegass, director of regional mobility and infrastructure for the Greater Washington Partnership, acknowledging the difficulty and competition the project faces. “We saw this year in the budget how we really only got $100 million for statewide transportation projects. And so, the political feasibility of funding a $1 billion project in Baltimore when we’ve got western Maryland and eastern Maryland and the D.C. suburbs all clamoring for things even though for those of us who live in the Baltimore region, we probably are like, well, it’s high time for Baltimore.”

Sacks said Moore needs to make a conceptual argument for why the focus should move to Baltimore.

“It’s not a billion dollars,” he said. “It’s $200 million a year and it has to be sold that way. You have to make the conceptual argument that we’re building something good here, and this is the amount of money that we took out of the red line to begin with and didn’t replace it really with anything.”

Other legs that extend further west include significant tunneling and have no initial estimates from the group. Rail projects — especially subway projects — can be prohibitively expensive.

A 2019 report by the Eno Center for Transportation found that New York City’s Second Street Subway project cost $2.6 billion per mile. San Francisco’s Central Subway costs about $920 million per mile and the Los Angeles Purple Line subway extension cost $800 million per mile.

Light rail is also expensive.

The 16.2-mile, 21-station Purple Line project that will one day link Prince George’s and Montgomery counties will cost $1.4 billion more than the original $2 billion estimate. The total cost of the state’s public-private partnership agreement to build and manage the line has increased from $5.6 billion to $9.3 billion. That line is expected to open in 2026 — four years behind schedule.

The idea offered by the west Baltimore activists comes as state transportation officials are looking at options for reviving the Red Line.

The original 14.1-mile line proposal connected East Baltimore to western Baltimore County.

Then-Gov. Larry Hogan (R) canceled the project in 2015. He called the $2.9 billion plan, which included extensive tunneling, “a boondoggle.”

“At that time, my position was that the decision to cancel the Red Line was a partial mistake,” said Al Barry, a former Baltimore City transportation planner who is working with the Edmondson Community Organization. “The entire Red Line I had been opposed to but I did feel that the governor was mistaken in canceling the west part of it, the west side part of it.”

Moore has said resurrecting the Red Line, sometimes called an east-west transit corridor, is a top priority.

The governor wants a transit system that connects underemployed areas of the Baltimore region to job centers. He’s tied the efforts to his focus on social and economic justice and reducing childhood poverty.

What Moore’s ultimate plan would look like, or cost, remains elusive.

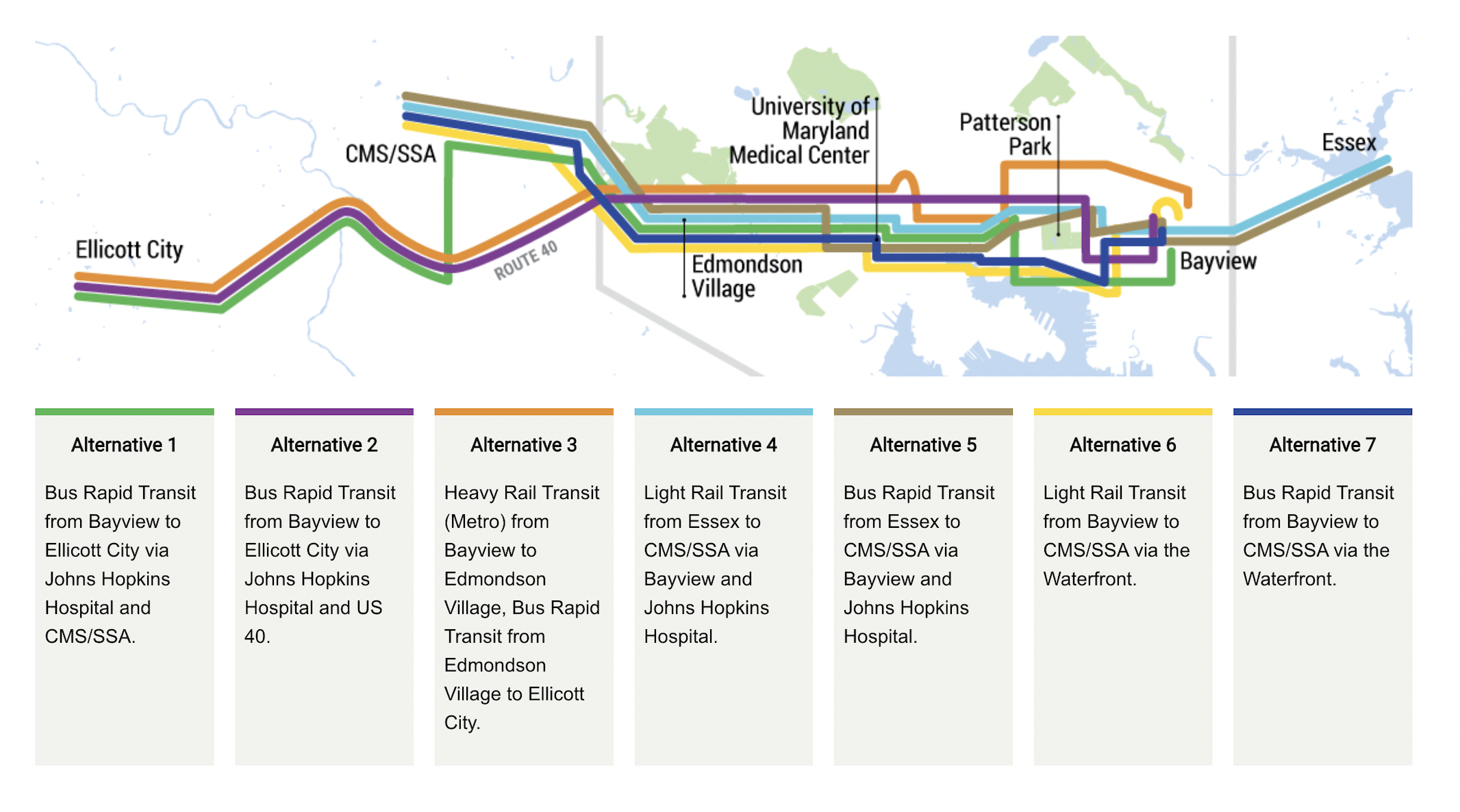

The Maryland Transit Administration last year unveiled seven potential east-west transit routes to serve the Baltimore region. The project is part of the Baltimore Metropolitan Council’s regional transportation priorities for the next 25 years. Screenshot.

A long-range transportation plan released by the Baltimore Metropolitan Council envisions a new Red Line project. The 25-year plan includes roughly $4 billion for transit corridors in the Baltimore region.

Part of that placeholder is for what would ultimately be a Red Line replacement. The initial cost is based on the average of seven potential options that were part of a 2022 study.

“So, to be clear, this is a proposal,” said Sacks. “We don’t have a special line to the governor. We haven’t talked to the governor. We haven’t talked to [Transportation] Secretary [Paul] Wiedefeld. This is a proposal. This is us throwing this out there and saying hey, we think this makes sense. But we’ve heard that the governor is considering other options. And he should be.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution