Building a Maryland wildlife corridor by the yard

Honeybee losses are at record highs across the nation, with Maryland beekeepers reporting a 55% winter loss in 2021, the second highest in the country, according to an annual survey from the Bee Informed Partnership, a national collaboration of research laboratories.

And it’s just not bees. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources warns that habitat loss and invasive species imperil the state’s 1,200 rare, threatened or endangered native species among the more than 15,000 species listed. Even common species are at risk, it says.

This map posted at the entrance to the Mount Rainer Community Food Forest is a guide for visitors. Image courtesy of Torie Partridge/Terratorie.com.

Residents in Mount Rainier are waging a local campaign to curb such losses. This small suburban town of around 8,300 bordering Washington, D.C., began in 2020 to transform the 31st Street Mini-Park into the Community Food Forest. City Councilmember Luke Chesek helped propel the project through government hurdles. The new design for the repurposed park features crescent-shaped berms to catch rainwater and a forested ecosystem with multi-layered beds of native trees, bushes, plants, herbs and flowers.

On a sunny day in early March, Chesek, with sons Austin and Finn, came for a stroll.

“Lots of the stuff is edible, either for wildlife or humans or both,” he said, walking down a central path and through a meadow maze. “We’ve got serviceberry trees, red chokeberry, blueberry bushes, and a pawpaw patch.”

A child has her eye on the blueberry patch among the many edible plants at the Mount Rainier Community Forest. Photo courtesy of Steve McKinley-Ward.

With the change of seasons, Chesek expects plenty of nuts, seeds, herbs, and berries. “We’ll have residents foraging, when stuff is in bloom,” he said.

Planted among the berms are kitchen staples like oregano, parsley, chives and peppermint. There will also be kale, artichokes and more veggies. It’s a place where bumble bees, birds, and bugs will settle in among sunflowers, golden rod and common milkweed, the latter a stopover for migrant monarch butterflies to feed and breed.

Building a network by the yard

The Community Food Forest has become the nexus for the Mount Rainier Native Plant Network. Chesek wrote a city ordinance that would promote converting any private or public green space in town into native habitat for wildlife to migrate.

“Our state and national preserves, as great as they are, aren’t enough, and our suburban and urban landscapes are going to have to be part of the solution to biodiversity loss and climate change,” he said.

Inclusion in the network requires 25 native plants on a single property. More than 30 yards and public spaces made the cut in 2021.

This spring, Chesek expects to add more among Mount Rainier’s 1,000 single-family homes, and is also encouraging apartment dwellers in the northern part of town to join in as well.

“We want to figure out ways to incentivize getting native trees and bushes all over these properties,” he said. “And, in that way it is [also] an equity issue.”

Joining forces with the Maryland Chapter of the Sierra Club, and its 70,000 grassroots members and supporters, Chesek sees an even greater opportunity to extend the network.

The Sierra Club chapter’s Natural Places Committee asked Chesek to scale up the network statewide, and to push it into neighboring states as the head of a committee workgroup.

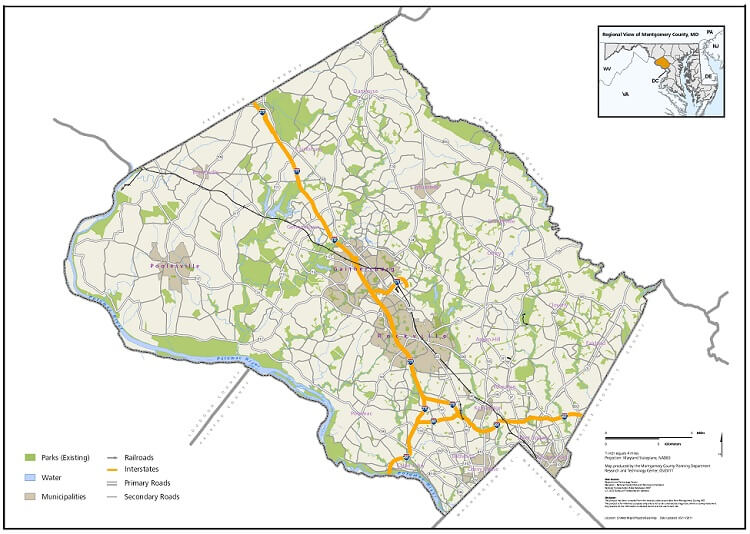

With an eye on Google maps and the protected features in the region, he has outlined a potential wildlife corridor that runs from the Appalachian Trail to the Chesapeake Bay.

“[There’s] a path from the Patuxent Wildlife Refuge through Greenbelt Park in College Park, to the Northwest Branch Trail,” he said.

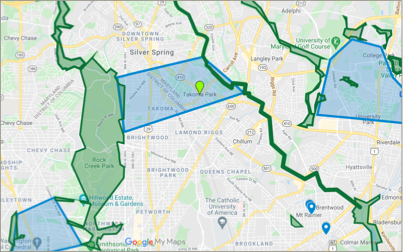

Green spaces in yards, apartment patios and shared public spaces can connect isolated habitats into a corridor for wildlife. Map courtesy of Sierra Club Native Plant and Wildlife Corridor Workgroup.

But there are gaps, he said, especially in urban areas such as Takoma Park, a key link between greenways on the northwest branch of the Anacostia River and Rock Creek Park in Washington.

“So we started focusing on Takoma Park, and we now have a bunch of houses [there] that are part of an [interactive map] on the workgroup website with entries from Damascus to Prince Frederick,” he said, encouraging others in the region to convert their properties into native habitat and adding them to the map.

Pollinator friendly bills in Annapolis

This work is at the heart of several pollinator-friendly bills before the Maryland General Assembly, said Sierra Club’s Michael Wilpers, who has testified on legislation.

Several measures are moving through the legislature with favorable reports from House and Senate committees.

The Pollinator-Friendly Powerlines Bill (House Bill 62/Senate Bill 62) exempts electric powerline corridors from local weed-height ordinances, “opening up 2,000 miles, and about 50,000 acres of powerline corridors for pollinator habitat,” Wilpers said.

The Maryland the Beautiful Act (House Bill 631/Senate Bill 470) creates a revolving loan fund for land acquisitions by small land trusts, “some of which will probably be meadows or grasslands,” he said.

And, “on the level of gardens and landscaping, the Native Plant Program [House Bill 950/Senate Bill 836] will help homeowners find native plants [at local nurseries] so their gardens will better serve our native insects.”

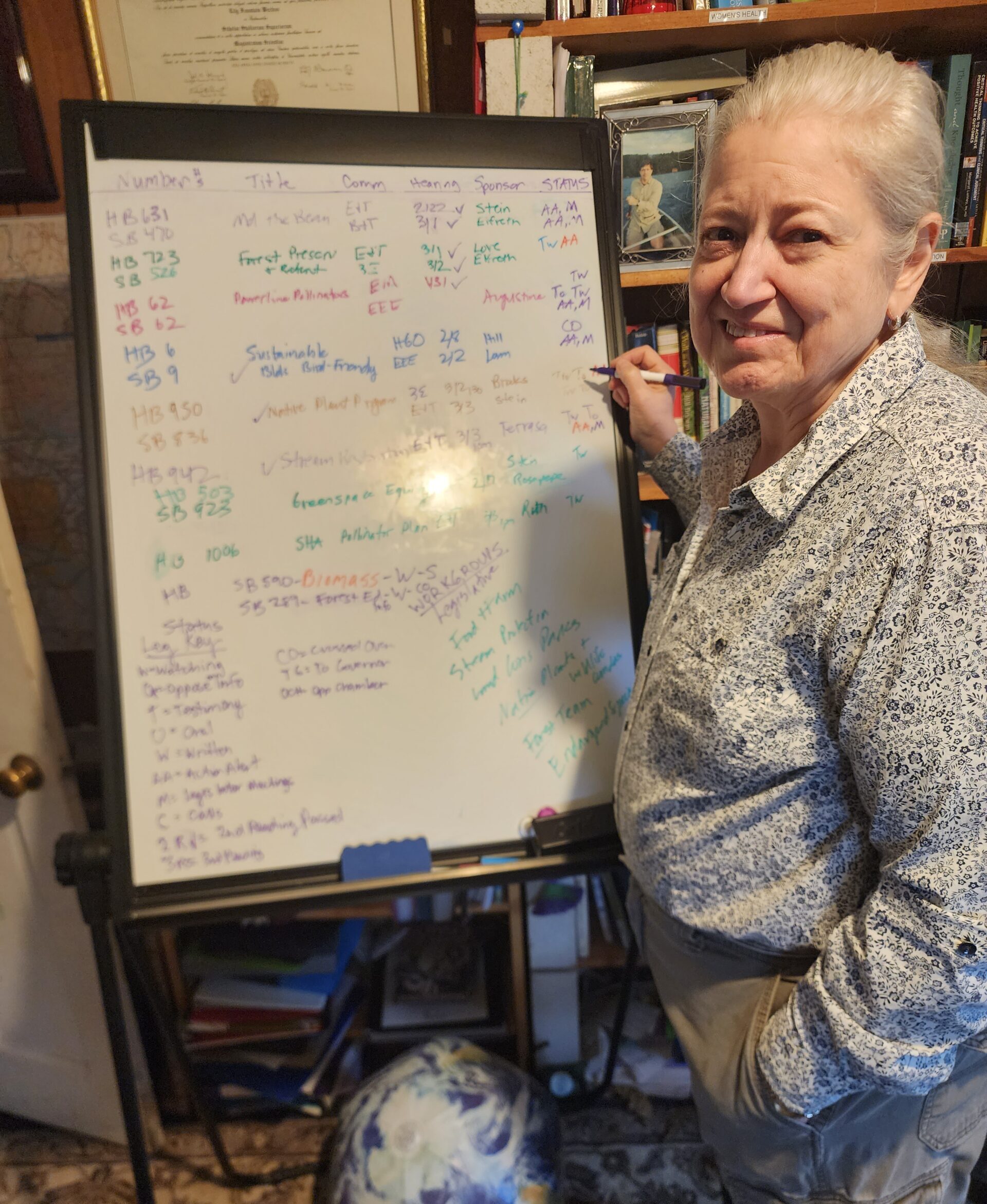

Lily Fountain, chair of the Natural Places Committee for the Maryland Sierra Club, keeps track of the many pollinator bills pending in the General Assembly this session. Courtesy photo.

Wilpers said wildlife habitats on existing highways can also make a big difference. Another bill, House Bill 1006, would require the State Highway Administration to create a plan that, with less mowing on 18,000 miles of state roads, would increase habitat for pollinators. “[This] addresses serious declines in our pollinating insects — such as bees and butterflies — that are essential to our fruit and vegetable crops and to nearly 90 percent of our wild trees, shrubs, and flowers,” he told legislators.

As support for the measure, Wilpers pointed to a 3-year study published in 2019 by the University of Maryland which found that roadsides have great potential for supporting pollinators.

“It showed that a single annual mow of roadsides [in Frederick and Carroll Counties] along with selective [careful] use of herbicides, allowed these roadsides to produce 68 species of native plants and support 83 species of native bees,” he said.

For his part, Luke Chesek is committed to making his community a better place to live — for residents and wildlife alike.

“I’d love for [Mount Rainier] to be more forest, more wildflowers, more butterflies, and more bees, so when you drive or walk through, it feels like you are in a much more alive place,” he said. “I hope we can grow that to our neighboring towns and everywhere across the DMV.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to correct the status of House Bill 1006.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution