Maryland Redistricting Case Part of Broader Legal Debate

Three U.S. Supreme Court gerrymandering cases originating in Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina could change control of one state capitol and possibly establish a new standard for how far states can go in drawing partisan political boundaries after the 2020 elections.

As statehouses prepare for redistricting, the once-a-decade re-drawing of electoral maps following the 2020 census, lawmakers are turning to the courts for guidance on how to create political districts that benefit the majority party without violating the constitution.

In Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, the high court will hear a Republican appeal of a lower court’s order to redraw 11 state legislative districts where large numbers of black voters were concentrated. Critics say racial gerrymandering, or “packing” minority voters into a few districts, limits their influence and violates their free speech and equal protection rights.

If the court rules against the plaintiffs, Democrats, who fell just short of retaking the Virginia House of Delegates in 2017, could find an easier path to majority control if the reconfigured districts are allowed to stand for the state’s 2019 elections. Earlier this week, the Supreme Court rejected a request by Republican legislators to halt work on the new maps until the case is decided.

Before the Supreme Court appeal can move forward, Republican plaintiffs must file written arguments that establish their legal standing to challenge the redrawn districts.

While the Supreme Court has previously struck down political boundaries that divide voters along racial lines, justices have never set a legal standard for what constitutes excessive partisan bias in the crafting of electoral maps.

In March, they will get another chance to do so when they review lower court rulings in two partisan gerrymandering cases that claim Democrats in Maryland and Republicans in North Carolina both created unconstitutional congressional districts that unfairly favored their parties.

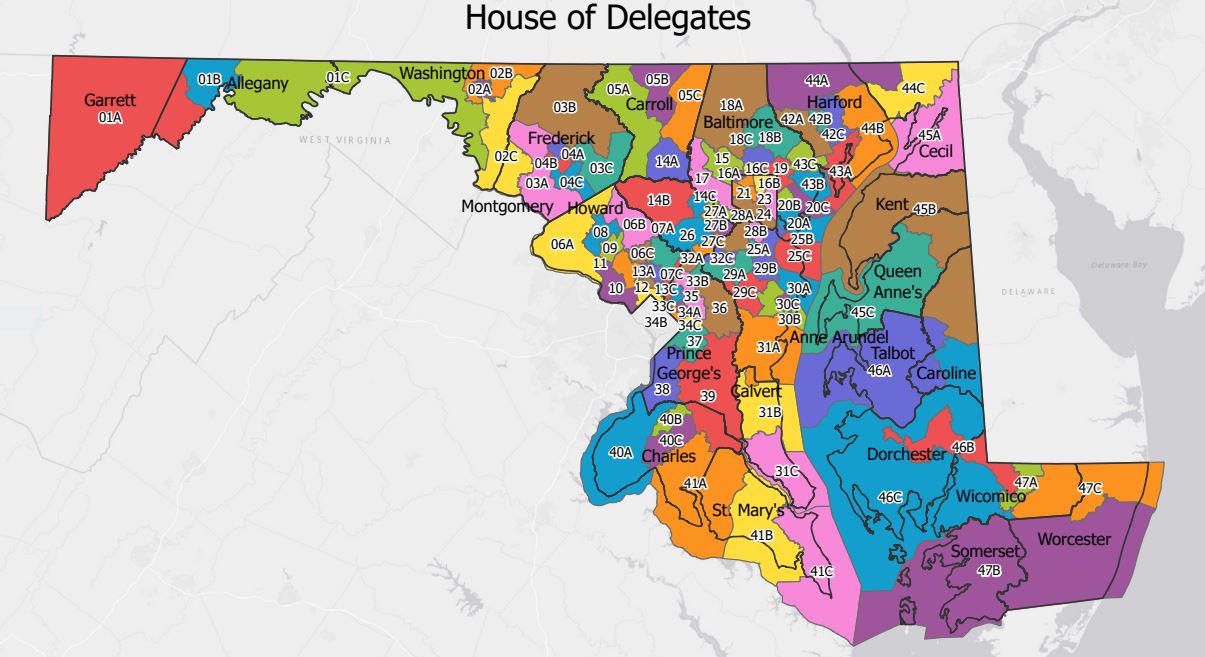

Plaintiffs in Benisek v. Lamone claim Maryland Democrats changed a congressional district boundary to dilute the voting strength of Republicans.

In Rucho v. Common Cause, Democrats claim North Carolina Republicans minimized their voting clout by “packing” Democratic voters into single districts and “cracking” them up into multiple districts in the state’s 2016 congressional map.

“By striking down North Carolina and Maryland’s maps, the Supreme Court can send a message to the rest of the country that extreme partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, no matter which party does it,” said a recent statement from Paul Smith, vice president of the Campaign Legal Center.

The high court was widely expected to address partisan redistricting last year when the same Maryland case and a Wisconsin gerrymandering case came before the court. But in June 2018, the justices sent the Wisconsin case back to the lower court, while issuing an unsigned opinion in Benisek v. Lamone that affirmed a lower court’s decision allowing the 2018 congressional election to be held in Maryland’s disputed 6th congressional district.

The high court also sent the North Carolina case back to a federal three-judge panel to decide if Democrats and watchdog groups had legal standing to challenge that state’s disputed districts. When the judicial panel ruled that they did, Republicans appealed that decision back to the Supreme Court.

The high court’s latest opportunity to decide whether courts should regulate the crafting of electoral maps has focused attention on the newest member: Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, who replaced former Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Before retiring last summer, Kennedy, a conservative, was thought to be the wild card on partisan gerrymandering among the court’s five conservative and four liberal members, said Richard Hasen, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine.

In a 2004 case, former Justice Antonin Scalia said courts shouldn’t hear partisan gerrymandering cases because there’s “no judicially discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating” such claims.

Kennedy agreed, but in a concurring opinion, wrote that if “workable standards do emerge,” the courts “should be prepared to order relief.”

Kavanaugh’s position on partisan gerrymandering is unknown. But based on his conservative judicial leanings, Kavanaugh isn’t likely to share Kennedy’s openness to impose judicial limits on the legislative exercise of redistricting, Hasen said.

“Justices sometimes surprise us, so we can’t say for sure,” Hasen said. “… But he’s generally seen as a conservative justice and that would put him more in line with Scalia’s general outlook than with Kennedy’s.”

If the five conservative justices issue a decision affirming Scalia’s 2004 position, “it would be the end of trying to bring equal protection and First Amendment claims against partisan gerrymandering,” Hasen said.

Federal Voting Rights Act violations and racial gerrymandering cases still could be brought, Hasen added, “but it would close down the argument that partisanship alone in drawing district lines creates the basis for an unconstitutional claim.”

While such a ruling would largely be viewed as a victory for conservatives, the current political climate going into 2020 favors Democrats. That makes 2020 even more important in states that will vote for state legislators that year – Maryland is not one of them – because the party that controls the legislature after the Census will also largely control the redistricting process.

In Maryland, where state government is now split between Republican Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. and Democratic supermajorities in the House and Senate – which was not the case when Democrats had full control and drew the current 6th District boundaries — officials will be waiting to see if the Supreme Court orders the state to redraw the district before the 2020 election. Then there could be longer term implications.

“If the Supreme Court fails to set limits on this undemocratic practice (of extreme partisan redistricting), we will see a festival of copycat gerrymandering in 2020 the likes of which the country has never seen before,” Smith said.

Josh Kurtz contributed to this report.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution