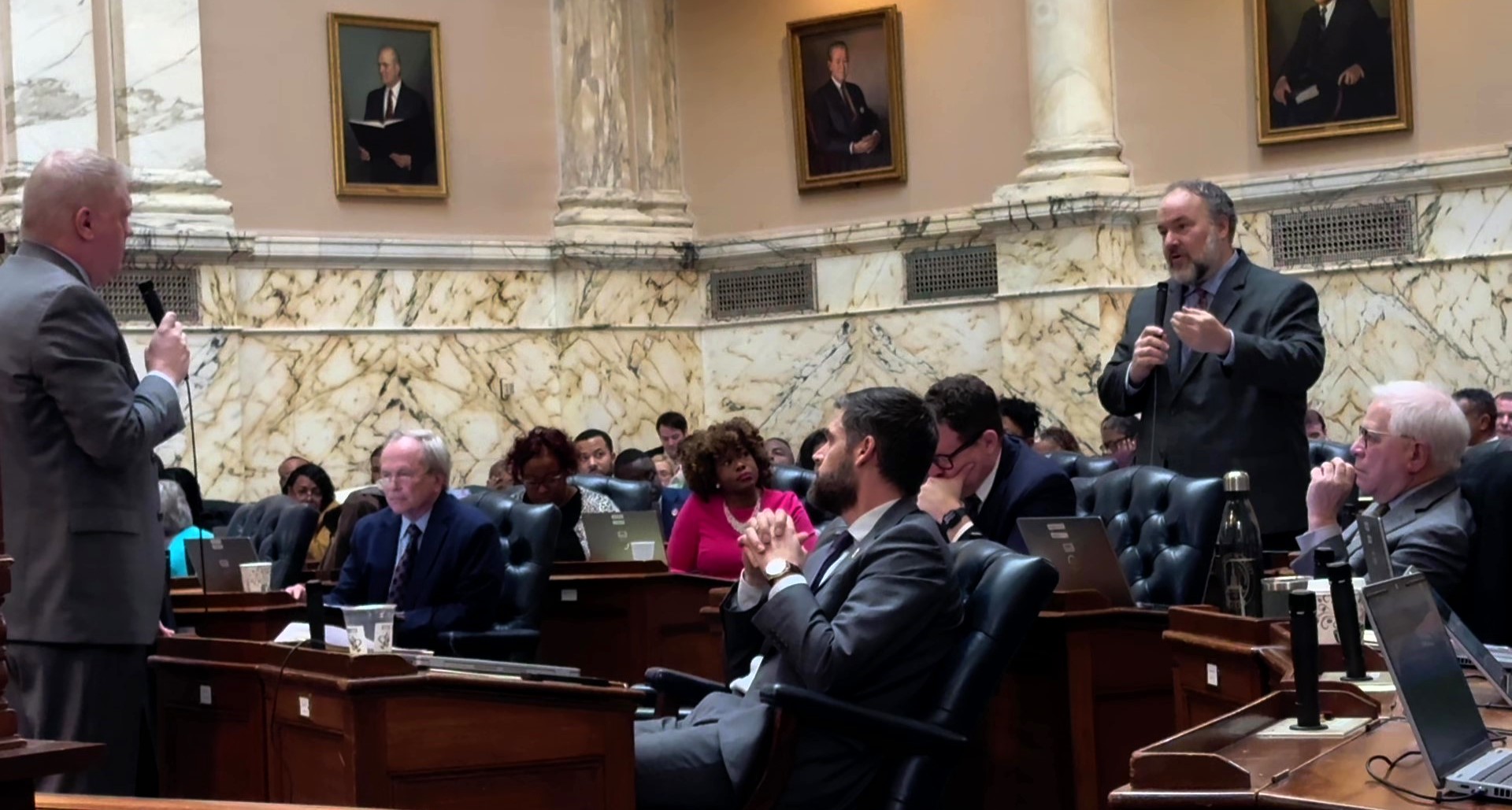

Legislation on juvenile justice measures that Maryland Democratic leaders want to combine with accountability and rehabilitation received preliminary approval Wednesday in the House of Delegates.

The debate on House Bill 814 lasted slightly more than an hour, which included discussion of four amendments the Judiciary Committee added to the bill on Tuesday night.

One of those amendments would require children ages 10 to 12 to enter a mandatory diversion program if a first-time arrest involves a car theft or certain firearm offenses.

House Minority Leader Jason C. Buckel (R-Allegany) asked what those programs would entail.

Del. Luke Clippinger (D-Baltimore), chair of the Judiciary Committee, said some jurisdictions offer diversionary programs either through nonprofit organizations or local police departments. Because some counties do not offer this service, Clippinger said the committee added a provision to extend the bill’s effective date from Oct. 1 to Jan. 1, 2025.

That would “give other police departments and not-for-profit organizations the opportunity to fill that gap so that first-time offenders can go to those programs and then hopefully, not come back,” Clippinger said. “The goal is to keep them completely out of the [juvenile justice] system.”

The House voted 97-35, mostly along party lines, to advance the diversion program amendment.

Another amendment that advanced is for the state Department of Juvenile Services to include in a three-year plan a program to help troubled youth ages 10 to 14 “who are at the highest risk of becoming victims or perpetrators of gun violence.”

Another committee amendment that the House adopted would require the department to provide a copy of its treatment service plan for youths to the Commission on Juvenile Justice Reform and Emerging and Best Practices. The plan, which must “explain attempts made to ensure implementation” of services must be filed to a court within 25 days.

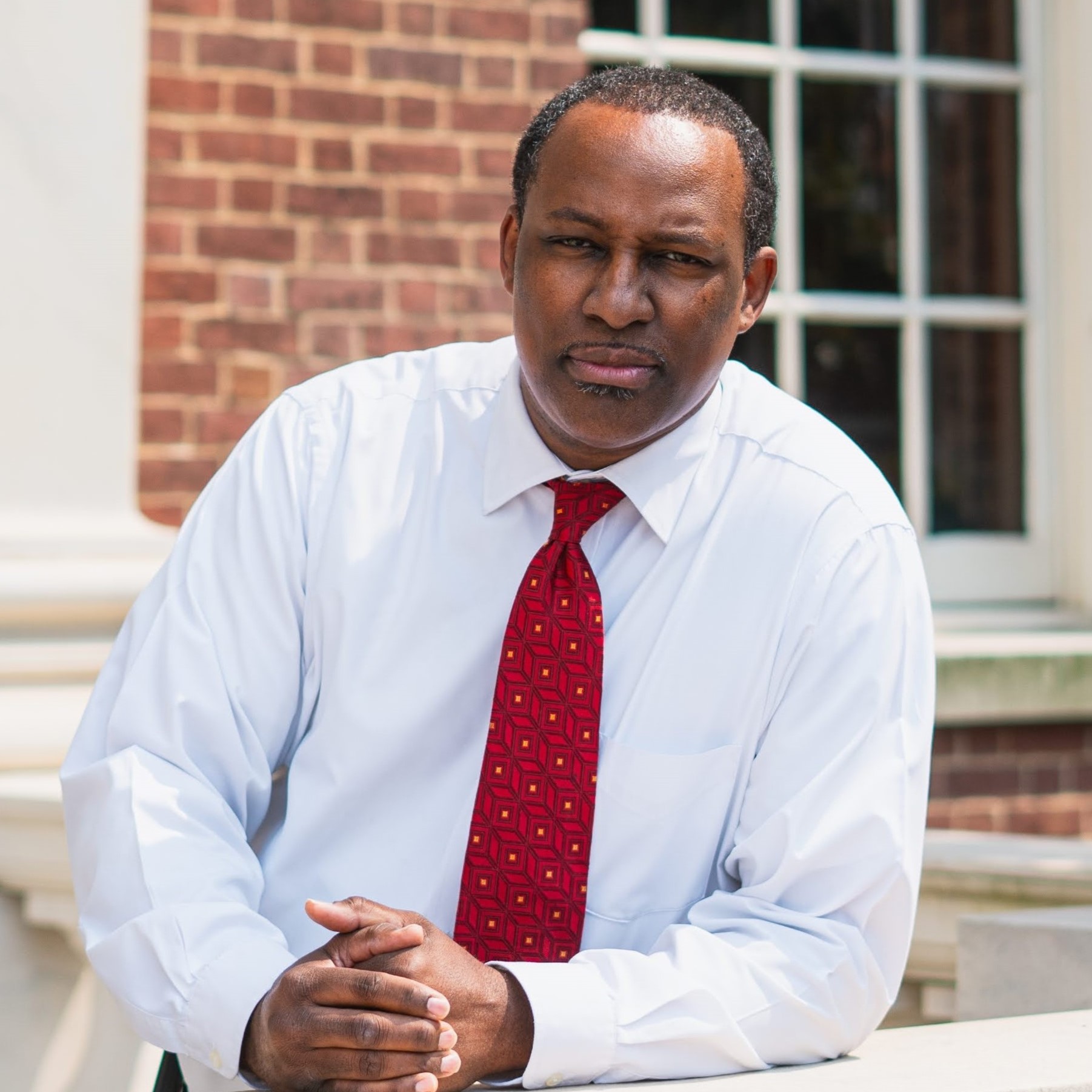

The House rejected four additional floor amendments that included two from Del. Caylin Young (D-Baltimore City) and one from Del. Gabriel Acevero (D-Montgomery).

Del. Gabriel Acevero (D-Montgomery County). Photo by Bryan P. Sears.

Most of the conversation on the House floor centered on an amendment from Del. Mike Griffith (R-Cecil and Harford) that would have allowed parents to waive a child’s right to speak with law enforcement officers.

“My concerns with this piece of the law: we do not want children who have done nothing wrong to be introduced into the criminal justice system,” he said. “That is precisely what is happening right now. This is not about taking rights. This is about restoring rights.”

Del. J. Sandy Bartlett (D-Anne Arundel), vice chair of the Judiciary Committee, said parents do not have the authority to waive a child’s rights.

“But the point is, the constitutional rights of that child remain,” she said. “The child’s individual liberties must be considered.”

Del. C.T. Wilson (D-Charles), a defense attorney and chair of the Economic Matters Committee, was more straightforward.

Wilson mentioned the infamous Central Park Five case from 1989 when Black and Latino teenagers in New York were charged with rape and attempted murder.

After serving years in prison, a New York Supreme Court justice vacated their sentences in 2002 after DNA evidence and a conviction from a convicted rapist proved their innocence.

“Those parents waived their rights for their children, too. We all know today that was a lie because some people don’t understand their Miranda Rights,” Wilson said. “In Maryland, we don’t want that to happen. The last thing we want someone to do…is to tell a child go ahead and say what you need to say. We don’t need a Central Park Five in Maryland.”

Griffith’s amendment was rejected 102-32.

The House could grant final approval of the bill by Friday.

‘Must do better’

Meanwhile, the Senate plans to debate its version of the legislation on Thursday, two days after the Judicial Proceedings Committee advanced the measure with amendments.

Most of the Senate and House versions jibe, including requiring a juvenile services intake officer to make an inquiry within 15 business days to decide whether the juvenile court has jurisdiction over a youth offender’s case and whether judicial action “is in the best interests of the public or the child.” The current law is 25 days.

Both bills also include many of the same representatives to join the best practices commission, such as the secretary of Juvenile Services, a representative from the state Department of Health and a person from a private child agency.

The amended Senate version has a representative from the state Department of Education also serving on the commission. However, the House bill deletes that and replaced it with a local school superintendent.

The Senate version proposes the legislation go into effect July 1.

If the full Senate advances the bill Thursday, it could receive final approval as early as Monday.

Several criminal justice reform advocates still express displeasure with the House and Senate versions, especially with extending jurisdictions of the juvenile court to include 10- to 12-year-old children.

Maryland Public Defender Natash Dartigue said in a statement released Wednesday morning that the Senate version “is a crime bill that dismantles the protections established by the 2022 Juvenile Justice Reform Act, disregards best practices for addressing delinquent behavior, and fails to look at long term impact.”

She continued in her statement: “In addressing public safety concerns, lawmakers must not exacerbate problems with actions taken in haste that lead to ineffective outcomes, fail to address the root causes of the problem, and have a lasting negative impact on children, families and communities. Maryland lawmakers can and must do better.”

Some unknowns

Both bills are equipped with a racial equity impact note from the state Department of Legislative Services, which highlights how the proposed reforms would broaden the juvenile court’s jurisdiction with children ages 10 and 11 years old.

Part of the note states how the bill “will likely increase Department of Juvenile Services (DJS) intake activity for youth 10 to 12 years of age as well as for older juveniles who meet various arrest and offense criteria. Any increase in intakes under the bill or other impacts — positive or negative — will likely affect Black youth to the greatest extent as they are significantly overrepresented in DJS custody, both in overall intakes and in the cohort of youths younger than age 13.”

According to the analysis, there were nearly 300 department intake complaints for youths younger than 13 during the last fiscal year, or 2% of the total intake for all juveniles. The department reported about 20 youths, or about 7%, were ages 9 and younger.

Although Black youth ages 13 and younger were 30% of the state’s population last fiscal year, DJS data shows about 64% of those processed for intake complaints in that age range are Black.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution