The writer is a professor of political science at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, and author or co-author of five books. This analysis originally appeared on the Sabato’s Crystal Ball blog at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Next November, Democrat Joe Biden may do what roughly two-thirds of incumbent party presidential nominees who ran for reelection have done: win reelection. In the U.S. House, court rulings in key redistricting cases, coupled with the political fallout from the Republicans’ internal chaos, gives Democrats a fighting chance to recapture the lower chamber. Because Democrats are playing defense in far more U.S. Senate seats, however, the GOP might flip the Senate.

Should this not-so-far-fetched scenario unfold, the 2024 election will deliver two results unprecedented in modern American history. First, party control of both chambers will have flipped, but in the opposite direction, in the same election cycle. And second, divided government will take the form of a Republican Senate offset by both a Democratic House and White House.

The first outcome may seem the more remarkable of the two. But given the Republicans’ narrow House majority and the Democrats’ even narrower Senate margin, control of both chambers could very well switch in opposite partisan directions.

More astounding is that one has to go back to the late 1800s to find an instance of divided government taking the form of a Republican Senate and a Democratic president and House. Since 1968, all five of the other six possible permutations of divided government have occurred except Republicans controlling just the Senate. Given that the Constitution allots two senators per state regardless of a state’s population, there is a clear tilt to the Republicans in Senate elections (which I’ll explain below). Yet there is an absence of a Senate-only Republican divided government that may be the greatest partisan anomaly of modern electoral politics.

Dealignment, sorting, and the GOP Senate advantage

The 1968 election remains the inflection point for modern American partisan elections. That year, the New Deal coalition collapsed and partisan dealignment began. Richard Nixon won narrowly and became the first U.S. president elected to his initial term without his party carrying at least one chamber of Congress. Even Nixon’s 49-state landslide 1972 reelection failed to flip either the House or the Senate to the Republicans. Democrats had held the House since the 1954 elections and would go on to hold it until 1994; Democrats also would hold the Senate for that entire timeframe, too, except for six years of Republican control starting in the 1980 election and ending in the 1986 election.

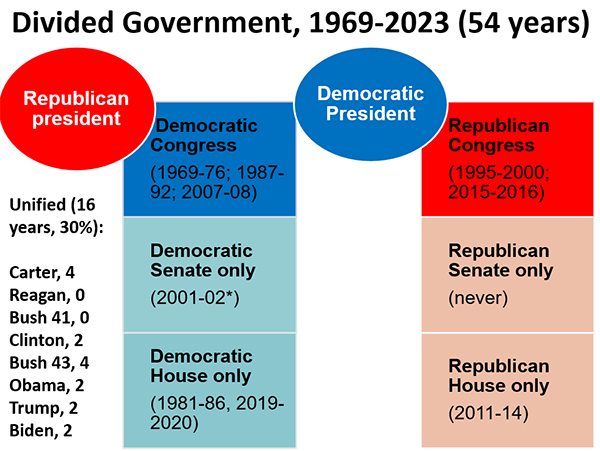

The 1968 dealignment led to the era of divided government we know today. In all but 16 of the ensuing 54 years (1969-2023), neither party controlled the entire government. Other than Jimmy Carter’s four years, Bill Clinton’s first two, George W. Bush’s* middle four (*see note under Figure 1), and the first two years of Barack Obama’s, Donald Trump’s, and Joe Biden’s presidencies, neither party has been able to claim a national trifecta. Along with Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, Nixon never enjoyed unified Republican control of the federal government.

Figure 1: Party control of government, 1969-2023

Note: *Vermont Republican Sen. Jim Jeffords’s 2001 party switch cost Bush 43 unified government for most of his first two years in office.

The 1968 election also triggered the gradual and sometimes rapid process of each party sorting itself regionally: Most moderate Republicans have nearly disappeared from New England and the Pacific Coast, while most (white) Democrats have also disappeared from the former Confederate states and the Plains.

Over the ensuing five decades, as blue states became bluer and red states redder, Senate election results became more reliably partisan. At present all but five states—Maine, Montana, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin—feature two U.S. senators from the same party; the 2024 replacement of West Virginia’s Joe Manchin and the defeats of Montana’s Jon Tester and Ohio’s Sherrod Brown could eliminate Democrats in three of these states and deliver Republicans the Senate majority next November. (For the sake of this argument, technically independent but Democratic-caucusing Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, Angus King of Maine, and Bernie Sanders of Vermont are counted as Democrats.)

Geodemography is the primary reason why a Republican Senate-only should be the most likely variant of divided government today. Senate malapportionment confers a slight edge to Republican presidential candidates in the Electoral College, as Bush 43 and Trump can personally attest through their 2000 and 2016 Electoral College victories, respectively. Rural-urban population densities also provide the GOP ways to strategically gerrymander U.S. House districts. But the GOP should benefit most from the highly malapportioned Senate and routinely win Senate majorities.

Understanding why requires a comparison of population differences between the median state and the nation. Because each state elects two senators, and either party needs to win half the states (plus one) to wield true majority control, any demographic group overrepresented in the states less populous than the median U.S. state is overrepresented.

Based on April 1, 2020 census figures, the median state population is 4.58 million people—the sum of Kentucky’s 4.51 million and Louisiana’s 4.66 million, divided by two. (The mean state population of all 50 states is 6.62 million.) The people who live in the 25 smaller states, from Kentucky down to Wyoming, wield disproportionate influence in building Senate majorities.

Presently, the GOP enjoys critical advantages in the population profiles of the smaller half of U.S. states. Specifically, those 25 states are more white, non-college educated, and rural—all features that favor Republicans:

Race: The median state is whiter than the nation overall. The share of white-alone, non-Hispanic residents nationally is about 58% according to the 2020 census, but among the 25 least-populous states, only five are more diverse than the nation overall (Alaska and Mississippi are just slightly under the national average, while Nevada and especially Hawaii and New Mexico are significantly below).

Race and education: The distribution of whites without college degrees is also disparate: As of 2018, 15 of the 23 states where non-college whites still comprised a statewide population majority are among the 25 least-populous states, according to calculations by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Twelve of the 15 states with the highest shares of non-college whites are also among the smaller half of states (Indiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin are the exceptions, as they are in the larger half).

Rurality: Nationally, about 25% of Americans live in rural areas, according to a FiveThirtyEight analysis. Because the average state is approximately 35% rural, rural voters are also overrepresented in the Senate. Although there are some very rural Democratic states (Maine and Vermont), the vast majority of highly rural states lean Republican.

Partisanship: Taken together, these factors contribute to the Republican tilt among small states. Among the 25 least populous states, 14 have voted for the Republican presidential nominee in each of the past six cycles compared to just seven that voted Democratic in each election from 2000 to 2020. Three others (Nevada, New Hampshire, and New Mexico) voted Democratic more often than Republican, while red-trending Iowa split three to three in those elections.

So because the 25 least-populous states are disproportionately white, non-college educated, rural and, consequently, more Republican, the GOP enjoys a formidable demographic advantage in the fight to control the Senate.

GOP Senate frustrations

Why, then, has the GOP not enjoyed a mostly uninterrupted string of Senate majorities? The short answer is two-fold: candidate quality and the Democratic surge in the Southwest.

In recent elections, Republicans have nominated some bad Senate candidates. Trump’s critics within the GOP warned that MAGA-aligned outsiders with weak political biographies, like Pennsylvania carpetbagger Mehmet Oz or scandal-plagued Herschel Walker in Georgia, would appeal to Trump’s base but turn off general election voters. They were right.

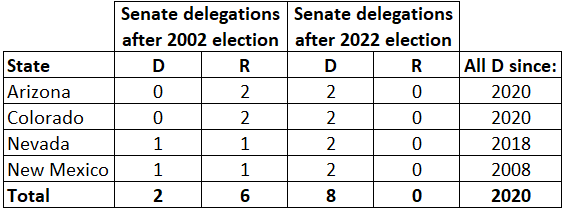

But what’s really denied the GOP sustained control of the Senate is the partisan shift of four southwestern states. Two decades ago, Republicans held all but two of the eight Senate seats in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico; today, the Democrats hold all eight (see Table 1).

Table 1: Partisan control of selected southwest Senate seats, 2002-present

Yes, during this same period Republicans beat or replaced some anachronistic, powerful red-state Democratic senators like South Dakota’s Tom Daschle, Montana’s Max Baucus, and West Virginia’s Jay Rockefeller. But add the Democrats’ recent capture of Georgia’s two seats to their net swing of six southwestern seats—the latter largely attributable to the four states’ growing Latino populations—and Democrats have been able to compete for control of the Senate despite their state-level demographic handicaps. (If I may toot my own horn, when I articulated the Democrats’ “non-southern strategy” in my 2006 book Whistling Past Dixie, the Republicans still held a majority of these eight Senate seats, but now Democrats hold them all.

In 2020, both Trump and Biden won exactly 25 states. Given how strong partisan attachments are, we should expect presidential and Senate results to line up. In fact, they do: Holding aside the five split-party Senate states listed above, the other 45 states were either won by Trump and have two Republican senators (22 states) or won by Biden and have two Democratic senators (23 states).

The perfectly split Senate of 50 seats for each party post-2020 was spoiled by John Fetterman’s capture of Pennsylvania’s open seat two years later, a win that gave Democrats their current 51-49 edge. Perhaps 50-each partisan Senate delegations is the new baseline in our polarized, blue/red America.

That may sound discouraging to blue state voters, because at best they’ll enjoy the barest of majorities. The fact that Vice President Kamala Harris recently set the record for tiebreaking Senate floor votes affirms this good-news-but-also-bad-news reality for Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and his fellow Democrats.

Still, given the underlying geodemographic dispersion of voters across the smaller and larger states, the GOP should be able to forge a Senate majority even when the party loses the White House and fails to control the House. The fact that Republicans have been unable to do so in modern times remains one of America’s most puzzling anomalies, but this certainly is a possibility in 2024.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution