Skepticism, questions remain as state seeks input on traffic congestion relief

Shayne Cochran walked the informational displays along the perimeter of a high school cafeteria in Frederick looking for signs of a shorter commute.

Cochran, a contractor, leaves his Frederick County home at 4 a.m. to beat the traffic to his office in Gaithersburg. He can be there by 5 a.m. — a commute that beats the 4 hours a day he spent in the car when he was also dropping off and picking up his son at school.

A proposed widening of sections of I-270 and the Capital Beltway and the American Legion Bridge hold the promise of easing daily commutes.

“I was horrible,” Cochran said, recounting his daily pre-pandemic commutes that now no longer include the daily school runs.

The Capital Beltway near the Interstate 270 spur. Photo by Dave Dildine/WTOP.

“I’m going in at 4 a.m. to arrive at 5 a.m. because of 270 traffic. It’s because of that,” said Cochran. “It would be nice to not have to get up at 4 a.m. to avoid that and be able to have sort of a normal commute.”

The open house at Frederick High School is one of three attended by a few hundred interested people like Cochran, according to Maryland Department of Transportation officials.

The meetings are an attempt to reboot the conversation around the project first announced by former Gov. Larry Hogan (R).

State transportation officials insist that a series of open house meetings in Montgomery and Frederick Counties last week is part of an effort to rebuild public trust. The intent is to seek community input on a revamped vision for easing some of the worst traffic congestion in the state.

A final open house is scheduled for 10 a.m. Dec. 2 at Thomas S. Wootton High School in Rockville.

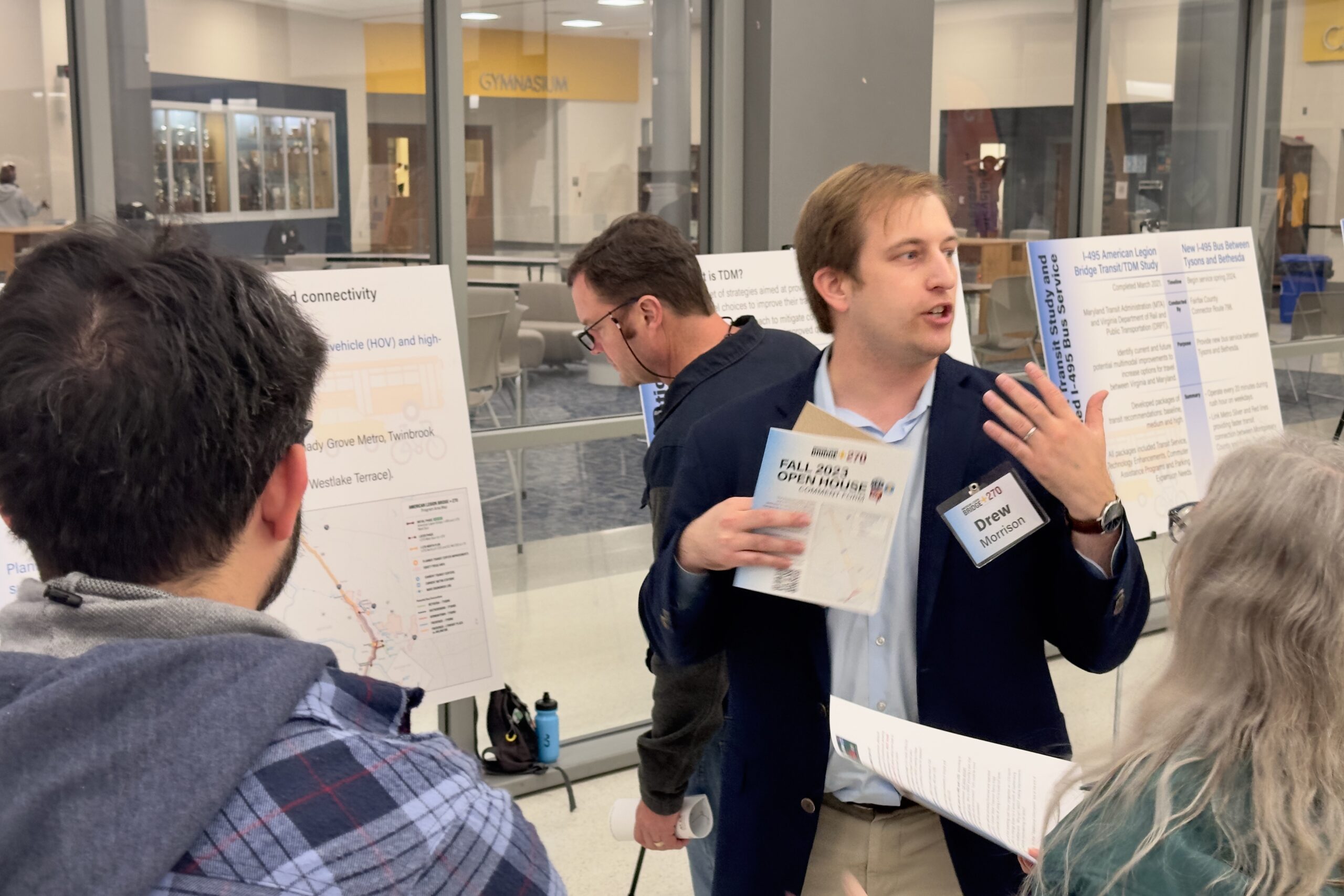

Drew Morrison, a policy adviser with the Maryland Department of Transportation, said the agency wants to “create a process that builds trust in MDOT from the get-go. We know we have a lot to do with that in terms of trust with the community.”

“I think that for us, it’s an opportunity to reset trust, try to listen and think more globally,” said Morrison.

Under the Hogan administration, the focus was on widening the bridge and highway using a public-private partnership. Under that plan, a consortium would have built and managed the project and set tolls. Some worried those tolls would leave some commuters stuck in soul-sucking congestion.

“People with money can get out of the traffic but if you’re the working poor, you’re screwed, stay in the traffic,” said Richard Kaplowitz, a Frederick County resident who has other ideas for how to solve the issue. “Federal money, state money bond issues have to happen. You have to have buses running all the time. Trains not tolls.”

Members of the public review options that could be part of a future plan to replace the American Legion Bridge and widen portions of the Capital Beltway and I-270. Photo by Bryan P. Sears.

The open house meetings include five stations laying out options. Each placard asks residents to consider options and preferences for how to pay for the project, transit options, bike and pedestrian features and other components of the project.

Morrison said the plan is to use the input from the open houses to refine a rough draft of a proposal that works within the existing federal approvals. That rough draft could be brought back to the public for additional comments sometime next year.

If all goes well, Morrison said the state could break ground on a project by 2026 and complete it by 2031.

The current focus is on a 6.5-mile stretch from the George Washington Memorial Parkway to the western spur of I-270. The plan would also include widening of the American Legion Bridge, a six-decade old structure that is a choke point for traffic and said to be nearing the end of its lifespan.

Future phases could address congestion from the west spur of I-270 to I-370, north of Rockville.

Displays at the open houses dangle the prospect of included transit options.

In August, Transportation Secretary Paul Wiedefeld said bus, vehicle and carpool would be initial options.

He would not, however, rule out express buses connecting Maryland and Virginia, ridesharing incentives and improvements to the MARC Brunswick Line and Bus Rapid Transit.

Wiedefeld, speaking in August, said those options are “a little bit further down the line.”

Morrison said Wiedefeld’s timeline remains with easier to implement options such as carpools and vanpools coming early. Bus Rapid Transit on parallel routes or expanded commuter train service would come later, if at all.

Some who were opposed to the original iteration of the project remain, so far, unmoved. Others worried about the lack of details or said they were watching to see if the actions of transportation officials matched their words.

At present, the state has only budgeted 3% of costs for expanding transit, a figure opponents say is too low.

“It doesn’t make sense,” said Barbara Coufal, co-chair of Montgomery County-based Citizens Against Beltway Expansion. “If this is aimed at providing congestion relief it’s not going to work. We think they ought to look at alternatives that will work such as expanded MARC service but there’s no money behind it.”

Paying for the project remains elusive.

Managed lanes — a euphemism for tolls — is still likely for portions of the projects that include widening the highway.

Cochran said he is not in favor of paying a toll to go back and forth.

“I hope there are no toll lanes between Frederick and Gaithersburg,” said Cochran. “I get the impression that maybe this whole thing here is somebody trying to sell us on toll lanes.”

The state has also applied for federal aid for the project.

Public-private partnerships are also not off the table for what Morrison said will be a “multi-billion-dollar project.”

Maryland’s Transportation Trust Fund is already overburdened. The state’s rolling six-year highway and transit plan known as the Consolidated Transportation Plan is short $2 billion.

The money in the account for state roads and transit projects can barely cover the costs of keeping the system in a state of good repair. That is before adding new projects including the I-495, I-270 or even the proposed Red Line in Baltimore.

A blue-ribbon panel is expected to recommend changes to how the dedicated account is replenished. The bulk of those recommendations are not expected before the end of 2024. They will require action by the governor and the General Assembly before they can be implemented.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution