Darlene Taylor was standing on West Main Street in Crisfield the other day and shouted a greeting to a woman she knew coming out of the Crisfield Discount Pharmacy. Seeing Taylor, the woman bolted across the street, to say hello and ask a question.

“What’s going on with the pigeons?” she wondered.

Taylor is not an ornithologist. Nor is she a hobbyist who keeps homing pigeons on her roof.

She’s the mayor of Crisfield, population 2,500, the southernmost incorporated town in the state of Maryland. Pigeons were roosting in an abandoned storefront on Main Street — a dead one was visible in the window on a recent afternoon — and it’s a topic of conversation in the small city.

Pigeons have taken over an abandoned city-owned commercial building on Main Street in Crisfield. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

Pigeons squatting in a city-owned building are hardly Taylor’s only problem — far from it. But they’re emblematic of a once-proud waterfront town on the Eastern Shore whose leaders are determined to buff up its decaying Main Street, reignite its struggling economy, attract tourists, and confront the ravages of climate change.

Once a year, Maryland’s political elite, and thousands of everyday people from all over the Mid-Atlantic, gather in Crisfield to eat crabs and drink beer. The J. Millard Tawes Crab and Clam Bake, held at a marina parking lot near the center of town, is a must-stop for most state political leaders, a chance to catch up, campaign, relax and gossip.

During the pandemic, the popular event, sponsored by the local Chamber of Commerce and named for an ex-governor who hailed from Crisfield, moved from the brutal heat and humidity of mid-July to the breezier early fall. This year’s version is scheduled for Wednesday afternoon, and for Crisfield, it’s one of a half dozen or so signature annual events that draw many visitors to the town.

“The exposure is just priceless,” said Taylor. “It’s huge for us economically. It’s huge for us for exposure. It’s huge for us politically.”

But what do political leaders see when they come to Crisfield? Most head straight to the Somers Cove Marina, where the crab feast takes place, and while perhaps a dozen or so political organizations, labor unions, business groups and civic organizations set up tents there, most political types gravitate almost immediately to the massive circus tent of a powerful Annapolis lobbyist, where they chat, sip and chew for the duration of the afternoon, without seeing much or meeting too many people outside their regular orbit.

Somers Cove Marina, site of the annual J. Millard Tawes Crab and Clam Bake, nine days before the 2023 event. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

What would these political leaders see if they looked around Crisfield?

For natural splendor, Crisfield is one of the most beautiful places in Maryland. Situated on a peninsula, surrounded by water on three sides, the town has stirring views and spectacular sunsets. It’s the gateway to Smith Island and Tangier Island, places that take visitors back to a bygone era. Janes Island State Park is one of the most distinctive in Maryland, with 30 miles of water trails, salt marshes, pristine beaches, campsites and cabins.

Crisfield still has a robust seafood industry — though it isn’t as big as it used to be — and good seafood restaurants. Crisfield, in fact, is so synonymous with seafood that there’s a famous seafood restaurant in downtown Silver Spring, just across the Washington, D.C., line, called Crisfield, which has been there for 78 years. The city of Crisfield has Somerset County’s only hospital, a super-modern public library overlooking the water, and a natural gathering place at City Dock, on the end of Main Street, an ideal venue for music festivals and fairs.

It’s hard not to be awed by the beauty of the place — and to see its potential.

“Crisfield is one of the most unique places in the entire world,” said state Sen. Mary Beth Carozza (R-Lower Shore), who represents the city. “I’ll put that view up against any place in the entire country and the entire world.”

But it’s also hard not to be struck by the challenges, which have been festering for years. More than two dozen storefronts on Main Street are abandoned, and some city-owned buildings were so decrepit that they had to come down. The city itself owns two blocks of empty commercial buildings on Main Street. Dozens of poorer residents live in dreary, moldy public housing units just across the street from the marina — though some resourceful residents take advantage of that proximity by selling parking spaces for crab feast-goers.

Crisfield isn’t much different from other small towns in the Mid-Atlantic — and across the country — that have seen their economies eroded and opportunities for ambitious young residents limited. Still, how the city got that way could fill a couple of books.

“Crisfield, like a lot of towns on the Eastern Shore, particularly on the Lower Shore, has the experience in the past of feeling left behind,” said Elizabeth Van Dolah, an environmental anthropologist with The Nature Conservancy, which is part of a team of organizations looking at flooding and resiliency in the city.

Abandoned storefronts on Main Street in Crisfield. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

Statistics tell part of the story.

The median household income in Crisfield, according to Census figures, is just $36,146 (it’s $48,661 in Somerset County and $91,431 in Maryland), and 27.7% of the population lives below the federal poverty line. Only 13.9% of the population has a college degree or higher, compared to 41.6% statewide. The median home value in the town is $110,100, compared to $143,600 in Somerset County and $338,500 in Maryland. The town is 57.2% white and 30.7% Black.

During its economic heyday, in the 1920’s, Crisfield’s population topped 4,100, at a time when Maryland’s population was about 1.5 million (it’s more than 6.1 million now).

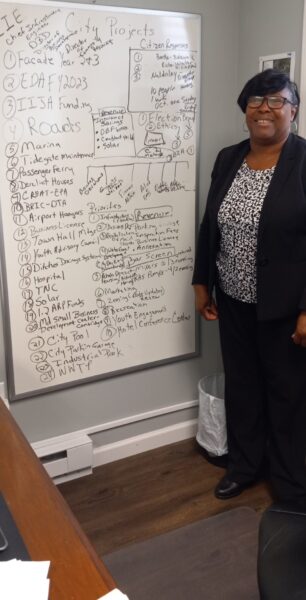

In her cramped office in Crisfield’s tiny City Hall, across the street from a Dollar General and a funeral home, Taylor, who was elected in 2022, has a whiteboard that’s scribbled with notes listing her priorities, the town’s greatest needs, and revitalization projects that are slowly getting underway. The sheer volume of items is staggering — from dealing with derelict houses to attracting ferry service from the Western Shore to building a hotel and conference center.

“How can you be a tourist destination if you don’t have a good hotel?” Turner said. “How are we going to get the foot traffic we need? People are going to stay for the day and just leave.”

Crisfield Mayor Darlene Taylor with her list of priorities in City Hall. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

Some of the items seem aspirational, or at least far from ever being accomplished. Others are starting to take shape.

“The real assignment is the future,” said Taylor, who looks over the list several times a day. “What can we do to improve the lives of the people that live here?”

In Crisfield, there’s almost universal agreement: Job No. 1 is improving the infrastructure in the town — and specifically addressing the nuisance flooding that frustrates residents almost every day, even during sunny weather.

“It has a big impact, because of how disruptive it is to daily life,” said Van Dolah, The Nature Conservancy anthropologist.

Residents recognize that living in a low-elevation town on the Shore can put them in the path of major storms and makes them vulnerable to sea-level rise. The problem, a range of people said, is that the town struggles to get rid of the water it takes in. The drainage system is antiquated and balky. Over the years, residents have filled in drainage ditches, for one reason or another. And the coastline continues to be battered.

“You will never stop the water from coming in,” Taylor said. “The best you can do is get it out quickly.”

Coastal resiliency ‘with people in mind’

A lot of smart people with institutional firepower are thinking about how to fight the flooding and protect the community from the rising tides.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is helping the city apply for what’s known as a Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) Direct Technical Assistance (DTA) grant. BRIC DTA supports communities that don’t have the resources to begin climate resilience planning and project solution design on their own. City officials, working with county and state leaders, have been developing their grant application and anticipate submitting it early next year — and are working with the federal government to determine the best use of these potential funds, which could total $50 million.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is partnering with the city to explore nature-based solutions to some of its flooding problems, such as green infrastructure and marsh restoration. While the agency is offering research assistance, city leaders say EPA will soon be launching a six-month Resilience Academy, open to those 15 and older, an interactive program for a small group of community residents.

The group Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake is working with congregations in and around Crisfield to help them address their stormwater and planting needs. And the Eastern Shore Regional GIS Cooperative, an entity that was launched by Salisbury University and uses geographic information system technology, has recently completed a mapping project of Crisfield’s ditches — and just as significantly, those that have been covered up, either by residents or by water that carried soil into the ditches and settled over the decades.

Crisfield also has received $2 million in government funding for a two-year project to repair and reimagine its City Dock, which has been battered by water and years of neglect. Step one will be protecting the perimeter from the rising waters. Step two will be improving the area to attract more tourists and cultural events, like the first-ever jazz festival that took place on the dock earlier this month.

A view up Main Street from the Crisfield City Dock. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

And the marina itself, with 500 boat slips, is about to undergo a facelift. Some of it is privately funded, and some of it comes from the state Department of Natural Resources, which is replacing bulkheads, piers and utilities. City officials envision connecting the marina to City Dock with a paved walking trail.

“The City Dock and waterfront development are going to work together,” said Taylor, who noted that the dock also serves as the launching place for ferries to Smith and Tangier islands, and also serves as a port. “It’s like a gateway to the city.”

But perhaps the most ambitious and comprehensive climate project in Crisfield is a collaboration between The Nature Conservancy, the EPA, George Mason University and the University of Maryland’s Environmental Finance Center, to bring flood adaptation support to Crisfield. Funding for this project comes from grants from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Adaptation Science Program and Lockheed Martin. Working with a 15-member advisory committee of Crisfield residents, the team is conducting an assessment of flood adaptation strategies to evaluate their costs and benefits for flood protection and community development goals.

Van Dolah, who grew up in coastal South Carolina and whose academic research focused on how to improve adaptation support for rural coastal communities on the Lower Shore, said The Nature Conservancy and its partners aren’t just searching for “nature-based solutions,” but are seeking answers that will help leaders in town achieve some of their long-term goals.

“We’re trying to think more about how coastal resiliency can be done with people in mind,” she said. “We’re starting by doing an assessment of community-selected strategies. I’m trained as an anthropologist, so I’m really interested in the concept of community resilience and what does it mean for Crisfield.”

Nuisance flooding is a major problem in Crisfield. The Somerset County Public Library is in the distance. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

Among options the researchers are considering: fixing and adding tidal gates in the area’s waterways; adding and restoring existing berms; elevating roads to make them less vulnerable to flooding; and building a seawall around major stretches of the town. The University of Maryland’s Environmental Finance Center is completing an assessment that won’t just include the financial estimates of each option, but will also look at the policy measures needed to achieve them as well as the possible political challenges.

“Our project team isn’t necessarily advocating for one route over the other, but we have put in a decision framework to give the city data points,” Van Dolah said.

‘We’re at that tipping point’

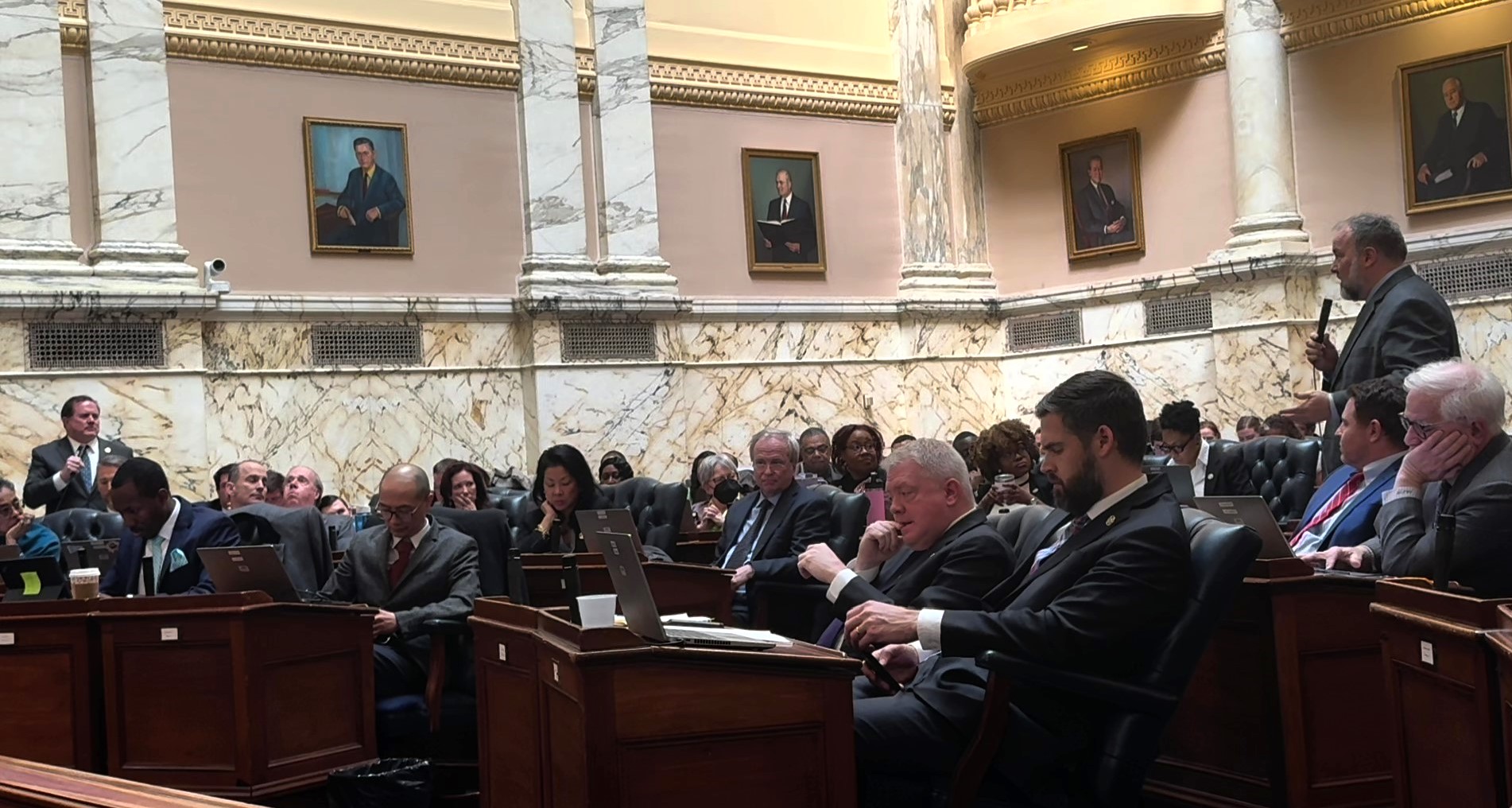

Carozza, the state senator, said there’s a healthy spirit of cooperation between local and state officials when it comes to helping Crisfield these days, and this makes her job of seeking state funding for important initiatives in the city easier.

“It puts me in a really strong position to advocate,” she said.

Carozza also called out Charles Laird (R), the president of the Somerset County Commission, as being particularly helpful to the cause. He’s worn many hats during his career, including corrections officer, poultry farmer, and commercial fisherman. He also serves on the Critical Area Commission for the Chesapeake and Atlantic Coastal Bays, so he is attuned to the challenges and opportunities Crisfield faces as a waterfront community.

“He’s extremely knowledgable about what’s doable,” Carozza said.

Several people said they have detected a new spirit and sense of purpose in the city since Taylor became mayor last year.

Taylor, 60, grew up in Crisfield, but spent 20 years in the Washington, D.C., area, working for a federal contractor. She would return to her home town from time to time to visit relatives, but didn’t move back permanently until 2005 — and what she experienced shocked and dismayed her.

“I realized home wasn’t the place I left,” she observed. “Nothing prepared me for the day to day living here. Depressing, to say the least.”

Soon after arriving, Taylor noticed the lack of after-school activities and opportunities for young people, so she launched a nonprofit called It Takes a Village to Help Our Children, Inc. The organization, situated on Main Street — where it has a capital campaign underway to build a new headquarters — now offers an array of after school programs, tutoring services and college prep classes, and also runs a summer learning and recreation program.

Taylor said she never imagined a career in politics for herself, but says that in 2022, as she was walking down the street looking over the abandoned buildings on Main Street, God spoke to her and advised her to run for mayor. As a woman of faith, she listened — though she procrastinated and didn’t file the paperwork to become a candidate until 15 minutes before the deadline.

“My faith is who I am,” she said. “I know if he called me to this, he had a purpose.”

Residents say they already see a change in the community and praise Taylor’s energy and passion.

“This administration is very pro-growth,” said Frances Martinez Myers, chair of the Greater Crisfield Action Coalition, a civic group whose members include both lifelong Crisfield dwellers and residents known as “come-heres.” “Clearly we’re very excited about it and we’re happy to be working with them.”

A view of the sunset from inside the Water Front Cafe, the only sit-down restaurant in Crisfield that was open on a recent Monday night. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

Myers, who worked in the housing industry in the Philadelphia area before moving to Crisfield a decade ago, said real estate investors from near and far are starting to pay closer attention to the area — attention that’s sorely needed given the lack of habitable, let alone affordable housing. In Crisfield, even some charming old Victorian homes have fallen into disrepair.

“Compared to other water-oriented communities, our real estate is relatively inexpensive, especially in Maryland,” said Myers, a sailing enthusiast who decided to move to Crisfield with her husband as they headed toward retirement, after finding other waterfront towns in Maryland too costly. “We really think we can attract any number of people: Boomers who are retiring, people looking for affordable rentals, the elderly, first-time homebuyers, second homeowners, remote workers. We know that people are looking for small, quaint serene towns.”

Myers, like other leaders in the town, cautions that this is a moment for Crisfield that cannot be squandered.

“We’re at that tipping point,” she said. “The time is right. People are looking for communities like ours. We’d love to see Crisfield grow and we feel like we have the elements to make it happen.”

But change comes slowly.

Taylor has created several civic committees, to get as much participation and buy-in from as many sectors of the community as she can. And she’s mindful of the fact that so many of her neighbors are struggling financially and come from humble origins.

Taylor’s mother was a crab picker in a local crab house and her father had a job cooling the crabs that came out of industrial-sized steamers. She helped commission a new mural off Main Street that pays tribute to seafood workers. The artist, Michael Rosato, is best known regionally for his mural of Harriet Tubman in downtown Cambridge.

Just around the corner from the mural is an empty storefront that the city is envisioning to house a business incubator. The city recently secured a $500,000 federal earmark to help set the incubator up in a building that was built in 1928.

A new mural in downtown Crisfield pays tribute to seafood workers. Photo by Josh Kurtz.

And on and on it goes, step by step, building by building, block by block.

Taylor knows that some residents may be skeptical that improvements are coming. But she asks them to simply look at her — the first Black woman elected mayor of the city (though Catherine Brown, a former councilmember known as “Miss Catherine,” served as interim mayor for a few weeks in 1998 following the death of the incumbent).

“That in and of itself says change is in the wind,” Taylor said. “God has great intentions.”

The Tawes crab feast Wednesday will bring an array of state leaders to Crisfield, but many will simply duck into the tent erected by lobbyist Bruce C. Bereano and stay there. But that doesn’t bother Taylor.

Bereano has become a great booster of the town. He lists all of the community’s cultural happenings in his “political events” calendar that he circulates every few weeks to hundreds of politically-attuned Marylanders, and he hires Crisfield teenagers and other locals to work in the tent during the four-hour festival.

“They can’t wait,” Taylor said of the residents who will work in Bereano’s tent. “This is huge for us.”

What advice would Taylor offer to crab feast attendees?

“Come from the crabs, stay for the sunset,” she said.

And what does she hope they’ll take away from their visit, however brief?

“We have a lot going up here in little old Crisfield.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution