Change comes to the state elections board as DeMarinis takes the helm

In 2013, soon after the passage of an overhaul of state campaign finance law, Jared DeMarinis was handed a badge.

DeMarinis, then the state’s director of candidacy and campaign finance, was part of an overhaul of campaign finance laws in Maryland in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Citizens United three years earlier. The new law also gave DeMarinis and his office wider latitude to issue civil violations.

The toy badge was meant as a playful tease aimed at DeMarinis. Even so, DeMarinis was the new sheriff in town.

Linda Lamone

On Friday, DeMarinis takes over as the state’s elections director, succeeding Linda Lamone, who retires after a quarter century.

Again, DeMarinis, the unanimous pick of the bipartisan five-member board, is the new sheriff in town.

The 18-year veteran of Maryland’s elections agency becomes just its second elections administrator. Lamone, the first administrator, was a 26-year fixture at the agency and, sometimes, a polarizing figure.

“This is a generational change we’re about to undergo,” said Yaakov “Jake” Weissmann, a recently appointed member of the Maryland State Board of Elections. “Frankly, I think a lot of people would be intimidated by it. You’re succeeding somebody who has been there for 25 years.”

Not DeMarinis, according to Weissmann, who served as a top aide to Senate President Thomas V. Mike Miller Jr.(D-Calvert) and Sen. Bill Ferguson (D-Baltimore) and worked with DeMarinis on every major election bill that came through the legislature during that time.

“I think it’s just a genuine belief in American democracy, the right to vote being this sacred thing, and just wanting to make it work,” Weissmann said. “It’s easy to get cynical. In most of the political field, in my experience, elections is one of the issues to automatically be less cynical about, because it’s this great thing of people getting to vote and decide our leaders. I think Jared really is an idealist in that regard, and really believes to his core that this is a great thing that we get to do.”

Weissmann and others credit DeMarinis for being constantly available to legislators and policymakers looking for explanations to sometimes arcane election law.

The 2013 campaign finance overhaul contained changes that were forward-looking for the time, Weissmann said.

“I don’t think we would have been talking about dark money, I don’t think we would have been talking about Super PACs the way that we were, if not for Jared,” Weissmann said.

“He was looking at where campaign finance was headed, and the increase in dark money and Super PACs, and talking about how we can increase transparency and find ways to to enforce transparency in a sector which seems to be specifically designed to get around transparency. That meant he had to do a lot of education of the commission members,” Weissmann said.

The bill also eliminated some popular loopholes including provisions that made it much easier for corporations with common owners to circumvent donation limits.

Another allowed slates of candidates to pool money and make unlimited transfers back and forth. The loophole became known as the Jim Smith Rule after the 2006 election. Smith, who was Baltimore County executive at the time, moved $450,000 into the Baltimore County Victory Slate, which he controlled.

The account then legally moved the money to Scott Shellenberger. The money replenished Shellenberger’s war chest and allowed the Democrat to win his campaign to become Baltimore County state’s attorney.

“This was a reform that Jared felt was really important for transparency and sort of for the public good in the thick of our elections and our integrity,” said Jennifer Bevan-Dangel, who in 2013 was the director of Common Cause Maryland. “It was colossally disliked by various groups who play the game and who participate in elections. I think it showed that he’s not the kind of person who’s going to bend or change his position just because it’s not popular or because the regulated entities don’t like it.”

Bevan-Dangel said DeMarinis was able to get buy-in from Democrats and Republicans because of his reputation.

“I think the legislators see that he’s not corruptible,” she said. “He’s not the gotcha agency, right? He’s not out there waiting for them to make a mistake and pounce on them. I think it also helps that they know he’s going to help them fix a mistake or understand what the rule means. He is unflinchingly and unswervingly fair and treats everyone the same. I think that if you talk to a Republican legislator or Democratic legislator or arguably a third-party candidate, they’re all going to have the same opinion that he is there to make sure that the elections work and that it’s not about personality and that it’s not about politics.”

Misinformation, malinformation and anger

DeMarinis enters the new job at a time when some are more cynical about elections and election administrators. Misinformation, malinformation and conspiracy theories sometimes swamp the truth.

“It’s hard not to harp on disinformation, but it’s out there,” said DeMarinis. “The thing with disinformation and malinformation, and misinformation, is the viralness of it. It’s spreading to the point where it is impacting the integrity of the electoral process, which then impacts the ability for people to govern.”

“I want to make sure that I’m definitely more accessible on social media platforms to help counter some of this,” he said.

He also acknowledges that two controversial national elections, the January 6, 2020, insurrection in the U.S. Capitol and the pandemic have changed attitudes toward those who oversee elections.

Some people are angry. Very angry.

DeMarinis, a widower who is now a single father of two teen daughters, knows the position he is in.

“That’s the other thing — the animosity towards election administrations for just doing their jobs out there,” said DeMarinis. “I came in with my eyes wide open on whether I would become a target or not. And, you know, I am a family man. And I had to have that as a consideration.”

“You know, I do take that seriously,” he said, adding that he felt pulled toward the new job. “It has to be done. Someone has to do it. I want to help stem this tide. I feel it’s an obligation.”

Dinner table politics

DeMarinis’ exposure to politics started around the dinner table in New Jersey.

“We always had discussions about it,” said DeMarinis. “It was always lively. And part of our culture was to make sure that everyone participated and voted.”

His mother, the procurement director of New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority, was active in 70s politics.

“She was very much into the equal pay argument as a professional woman,” said DeMarinis. “Seeing that and hearing about women doing the same or more than a man and getting paid less, I would say that kind of got me involved.”

After high school, DeMarinis found himself working on several campaigns, including for former Gov. Jon Corzine (D), and he was later on the staff of U.S. Sen. Robert Torricelli (D) before heading to law school at Rutgers.

It was there that he met his future wife Xan Desch. It was also while there that DeMarinis saw a path in election law.

“The seminal moment in everything was Bush v. Gore,” DeMarinis said. “So, 2000, with Bush v. Gore. I’m in law school, that case comes about. At that point it was clear to me that I wanted to get involved in the field of election law and doing elections. I’ve wanted to carve out my career based upon that and then I saw that you can. It was such a seminal moment in our history, and as well as just for me personally.”

‘Who wants to step up and fix it?’

DeMarinis’ soon to be former office is a bit of a time capsule.

There are few papers on his desk — a vestige of the move to work from home that sprung from the pandemic. On the day he was interviewed, the state board office on West Street was dark except for his workspace.

On his wall hang photos of personal trips. There are election posters in languages from far-flung countries around the globe where he has served as an election observer.

There are prints, including one featuring members of the Calvert family, founders of Maryland, as well as another, a reproduction of a print by Paul Revere portraying the Boston Massacre, which DeMarinis picked up during a trip to Massachusetts.

He is quick to point out that the print, which shows British troops as the aggressors, is not historically accurate.

“It wasn’t like this in reality, right?” said DeMarinis. “This was basically the first campaign material out there.”

DeMarinis pauses briefly when asked if the print was an early example of misinformation.

“It was more malinformation,” he said. “But it took a, you know, it stretched the truth a little bit there.”

DeMarinis laughs when asked about the message of the print. Combating misinformation and malinformation continue to be top of mind for him.

In 2018, he again worked with legislators to pass the Online Electioneering Transparency and Accountability Act. The law was an attempt to address concerns about campaign misinformation spread online during the 2016 election.

“We were a targeted state for the disinformation campaign,” said DeMarinis. ” I think that that’s still a part of things that we’re dealing with today.”

The law required websites accepting political advertising to maintain records of the purchases of “campaign material” including advertising. Those records would have to be conspicuously published within 48 hours. Other records would have to be maintained and available to the State Board of Elections on demand.

News websites balked at provisions requiring them to disclose online ad purchases and provide the name and address of the purchaser and the cost of the ad.

Nearly a dozen media companies in the state filed a federal lawsuit. A three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court ruled the provision violated the First Amendment.

“The court didn’t like it a whole lot,” DeMarinis acknowledged, but noted that additional regulations grew from that challenge.

“We’ve created deep fake regulations, to make sure that voters are at least aware,” he said. “There’s things that you can do to disinformation. We’re a trusted source. We’re going to try to make sure that the voters are informed. That’s the best we can do. We can give them all the information so that they can make an educated choice when casting the ballot.”

Even in his spare time, it’s the errors that DeMarinis seizes on and wants to fix.

One error about how the home of the president came to be called the White House in a 1984 publication led DeMarinis to author a book on the history of the Electoral College in the state.

“I was like, that’s a mistake,” said DeMarinis. “Then when I see a mistake like this in a document, I’m like, Alright, I got to look at everything. That’s the lawyer in me. Then it becomes who wants to step up and fix it?”

“All right, I guess it’s going to be me,” he said.

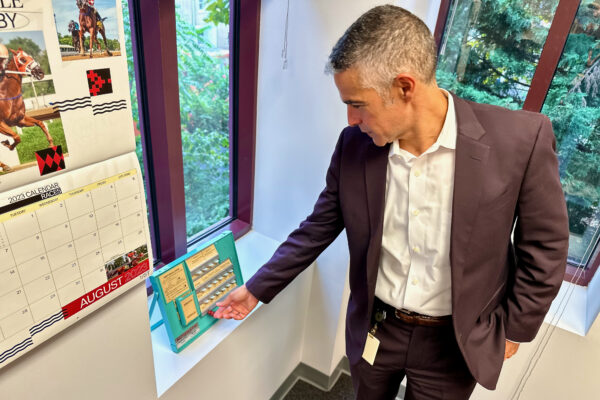

Incoming State Elections Administrator Jared DeMarinis shows of a model of a older lever-style voting machine no longer in use. DeMarinis said he’d one day like to see a museum to elections that would educate the public on voting. Photo by Bryan P. Sears.

On a ledge near a window in his office is a small replica of a lever voting machine. DeMarinis picks it up and talks about another idea he has.

“One of the things I wanted to kind of start doing is an election museum, or at least trying to create this concept of it to help people understand the importance of everything,” said DeMarinis. “And you get to see this stuff here, like how you vote off of this little contraption.”

Adapting to changing times

DeMarinis knows he has more pressing and immediate concerns than a museum passion project.

The generational change ushering him into his new job requires him to pick a new team.

In addition to the departure of Lamone, Deputy Elections Administrator Nikki Charlson has also left. Charlson was one of two finalists to succeed Lamone along with DeMarinis.

He is expected to name a new deputy administrator as soon as next week.

Also gone is Donna Duncan, a well-liked 45-year veteran of the agency.

The loss of Lamone, Charlson, and Duncan represents nearly 100 years of collective experience.

Two other employees — the board’s director of project management and procurement and the audit manager within the candidacy and campaign finance division — have also left to take positions in Prince George’s and Howard County governments, respectively.

Additionally, DeMarinis will also have to find someone to take over his old job.

“The million-dollar question is how is he going to find someone to replace himself who will live up to that standard?” said Bevan-Dangel. “You know, it does create a really interesting void.”

DeMarinis said he’s looking for a replacement with “the right temperament for the job.”

In recent months, DeMarinis has successfully sought fines against campaign committees and organizations. One of those, a $48,000 fine, was levied against a sports betting consortium that ran afoul of disclosure laws. It was the largest single fine in state board history.

DeMarinis said he would prefer to seek compliance without having to resort to fines.

While he searches for his own replacement, DeMarinis said it is possible he will also continue to do his old job.

And as proud as DeMarinis is of laws that passed in 2013 and 2018, the incoming administrator notes that they were in response to big events.

DeMarinis said the agency will have to learn to better anticipate trends and problems.

“There’s going to be some changes,” he said. “I’m a different person. We also have different issues that are facing us than in the past. You have to adapt with the times. I want to be more proactive and look at and see how things are going to affect elections.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution