As opioids overdose deaths keep rising, report urges lawmakers to develop new approaches

Lawmakers should view America’s staggering opioid crisis, including the rise of illicit fentanyl, through an “ecosystems” approach, argues a massive RAND Corporation report published Thursday.

That means they should examine the gaps and interconnections among emergency response, data collection, education, treatment, housing and law enforcement, the report advises.

The 600-page volume — which the authors describe as “arguably the most comprehensive analysis of opioids in 21st century America” — encourages federal, state and local lawmakers to think “beyond traditional silos” and innovate ways to stem adverse effects of addiction and increasing drug overdose deaths among Americans.

“There have been lots of initiatives and efforts to try to address it, but when we looked around, the majority, not all but the majority, seemed to fall in the silos — like, ‘We’re going to improve treatment,’ or ‘We’re going to focus on harm reduction,’ or ‘We’re going to decrease illicit use and try to decrease supply,’” said Bradley Stein, Director of RAND’s Opioid Policies, Tools, and Information Center.

RAND, headquartered in Santa Monica, California, is a nonprofit organization that focuses on several areas, including the U.S. military, education, national security and health care.

“One of the things we did was sort of step back and say, ‘Are there opportunities sort of between these systems, between the silos? And so thinking about it more as an ecosystem or more holistically, are there things and opportunities that we may be overlooking?’” Stein, one of the authors who is based in RAND’s Pittsburgh offices, told States Newsroom.

Overdose rates jump in recent years

Drug overdose rates in the U.S. have risen fivefold in the past two decades, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study published in December.

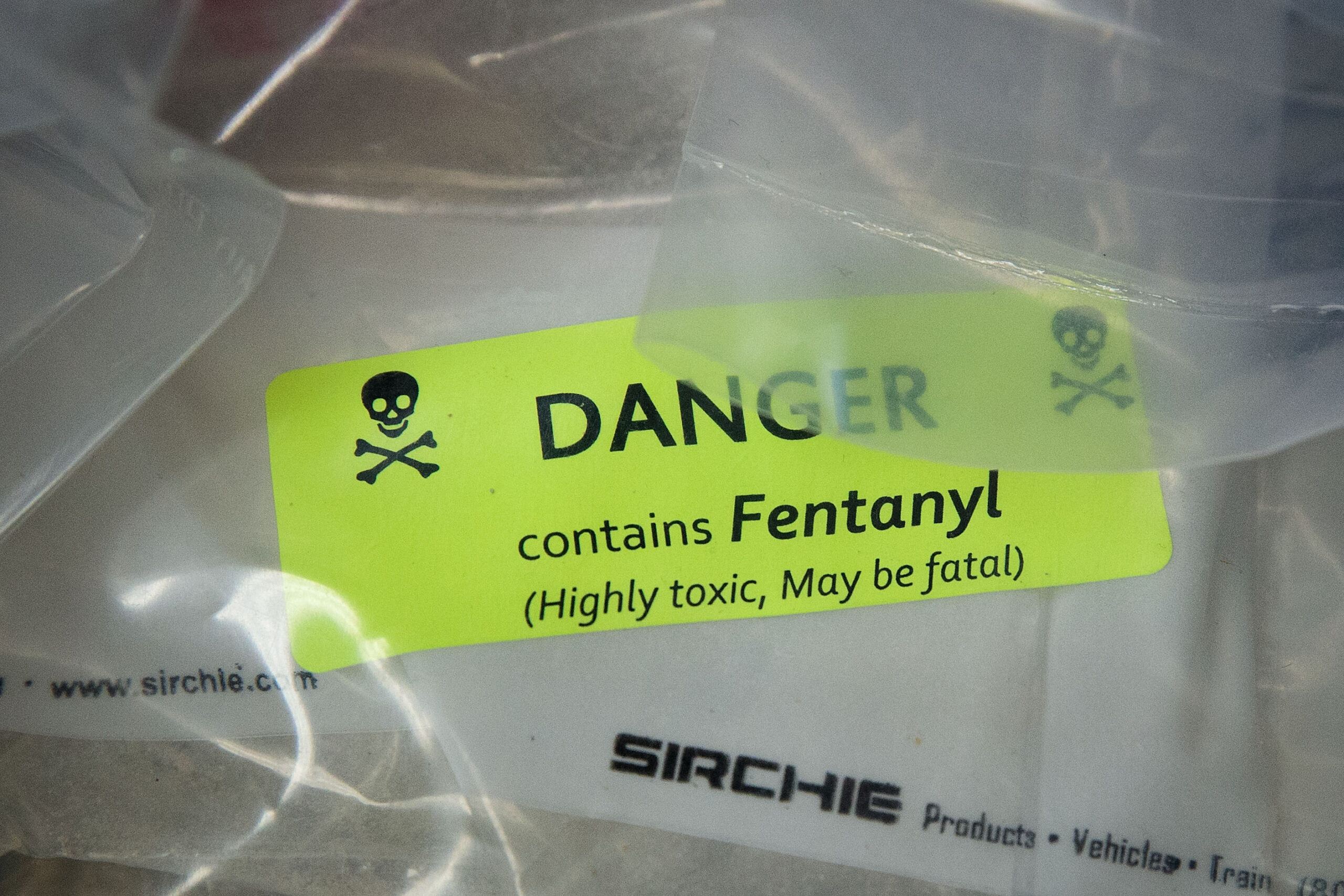

The study shows that deaths attributed to opioids, including synthetic opioids like fentanyl and its many analogs, have been steadily on the rise, with a staggering jump in recent years.

The CDC tracked a record 107,622 overdose deaths in 2021 — 71,238 of them were due to manmade, illegal fentanyl substances.

The agency defines drug poisoning overdose deaths as those resulting from the “unintentional or intentional overdose of a drug, being given the wrong drug, taking a drug in error, or taking a drug inadvertently.”

Illicit fentanyl ending up in other drugs — for example, counterfeit prescription pills, cocaine and heroin — has been the target of federal agencies and the subject of multiple congressional hearings and roundtables.

GOP lawmakers on the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee are poised to mark up the HALT Fentanyl Act, a measure reintroduced this Congress by Republican Reps. Morgan Griffith of Virginia, and Bob Latta of Ohio.

The bill aims to permanently classify fentanyl-related analogs as Class I substances under the Controlled Substances Act.

Just this month, a bipartisan group of U.S. lawmakers, including Democratic Reps. Joe Neguse of Colorado and Madeleine Dean of Pennsylvania launched the Fentanyl Prevention Caucus.

The group plans to tackle education and destigmatizing the opioid overdose-reversing medication Naloxone, said Dean, who is public about her son’s recovery from opioid addiction.

Not enough data

One of the gaps facing lawmakers as they try to legislate a solution is a lack of data. The U.S. is essentially “flying blind,” the RAND report states.

“We’ve had this opioid crisis for a while, but if we look nationally, there are still all these areas where we still don’t have a good sense of the magnitude of the problem. How many people use fentanyl, how many people are using heroin?” Stein said.

Stigmatization of users, unintended consequences of criminal penalties and a lack of communication across systems all hamper clear data collection that could improve people’s quality of life in other areas — for example, housing, child welfare and employment, the report argues.

However, some state and local governments are developing ways to bring data together, Stein said.

The report notes that Maryland has linked data across health care, substance use treatment, criminal and legal statistics, and mortality information.

Rhode Island has pulled several data sets, including valuable information collected from nonfatal overdoses and distribution networks of Naloxone, in one data center hub.

Pennsylvania’s opioid data dashboard, among other data, tracks the number of Naloxone doses administered by EMS personnel and emergency room visits for opioid overdoses

Tim Leech, vice president of Pittsburgh Firefighters Local 1, responds to varying volumes of drug overdose emergency calls that ebb and flow with the trends of local drug use.

“We are usually the first ones to encounter the patient. Once we’re there and we start treating the patient, the paramedics will arrive. And depending on the severity, it’s possible that a doctor could come as well after the patient’s care is handed over to the paramedics,” Leech said in an interview. “No matter what happens every call I go on, when I go back to the fire station, I (submit) information on our computer database, and there’s a code for overdoses.”

Dean talked about efforts in the Philadelphia area to coordinate care across institutions.

“We have an area of the city known as Kensington where some of the most difficult cases of mental health, poverty and addiction are all coming together,” she said, mentioning that she recently spoke to the Philadelphia-based Sheller Foundation about efforts to address overdoses.

“So literally what the (Sheller) foundation is doing is trying to bring together different hospital systems and nonprofits and recovery centers and housing to get at this problem in a very coordinated way instead of just one recovery at an ER and out goes the person with the problem to another ER.”

Advice to lawmakers

The RAND report, several years in the making, suggests a four-part framework that decision makers can use when thinking about crafting effective policies to help those with substance use disorders.

That four-pronged approach includes:

- Integrating issues and systems.

- Experimenting with new approaches.

- Developing roles for people who can take “ownership” across systems.

- Revamping data systems to better understand the problem.

The study’s authors built a searchable tool to encourage a “holistic approach” when policymakers are weighing how to tackle the opioid crisis.

“There’s not a silver bullet,” Stein said. “… Individuals with opioid use disorder move across so many pieces of this ecosystem. But often one part of the system doesn’t have a very good idea of what’s going on in another part of the system.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution