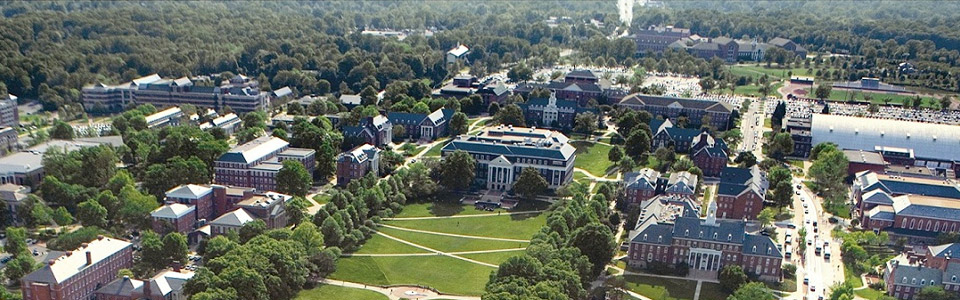

Back in the 1980s, when this story began, Maryland had at best an average system of public higher education. When experts rated how states compared on the quality of their public colleges and universities, Maryland was not part of the discussion. That didn’t mean that you couldn’t get a good education at a state school; it just meant that Maryland was not a national leader, not ranked among the best, not a resource that state officials bragged about as part of their economic development pitches.

Multiple studies were conducted by numerous state commissions, each of which resulted in reform recommendations that went nowhere. While there was widespread agreement that the state needed to do better, there was no consensus on what specific changes were needed. The last report landed in 1987 on the desk of the newly elected governor of Maryland, William Donald Schaefer.

Schaefer, famous for his “Do it Now” approach to governing, was not about to let another report gather dust. With only limited experience with higher education issues as the mayor of Baltimore for 15 years, he nevertheless recognized the potential that highly ranked public colleges and universities could have for strengthening Maryland’s economy, workforce and quality of life.

The legislation that eventually passed the General Assembly in 1988 went through a good bit of sausage making before it received legislative approval, but the result satisfied Schaefer’s primary objective: to make public higher education a top state priority. While some argued about the details of the structure and others worried that the flagship campus at College Park would somehow be diminished, all those naysayers were proven wrong.

Over the years since 1988, Maryland has consistently funded its public colleges as a key resource, even during times of recession. One governor, Bob Ehrlich, briefly broke that pattern, forced tuition to increase substantially instead of providing new state appropriations and lost his reelection bid. While there were many factors that led to Martin O’Malley’s victory in the gubernatorial election in 2006, the sharp contrast over who supported higher education was certainly a high profile issue. Moreover, ever since then, governors have kept a careful eye on tuition levels as a potentially third-rail issue.

Laslo Boyd

With widespread political support, public higher education in Maryland thrived in the years after Schaefer’s reorganization. In some years, every other state reduced its public appropriation even as Maryland’s increased. Even more importantly, every measure you can think of in terms of the quality and competitiveness of Maryland schools improved. The flagship campus is now among the leading public universities in the country, mentioned in the same breath as Virginia, North Carolina, Michigan and California. Measured by research grants won, private dollars raised, credentials of faculty and incoming students and achievements of graduates, the University of Maryland is a national leader.

The same can be said of many of the other state institutions when compared to similar types of universities. That certainly applies to the professional schools in Baltimore and the regional comprehensive campuses.

Up to this point, I might be accused of making a marketing pitch for Maryland public colleges and universities. Remembering the history is important, however, because the incredible progress of the past three decades seems at risk for the first time since 1988. Rather than rely on the cliched phrase of a “perfect storm”, let’s instead focus on a serious of events that have shaken public confidence in those charged with stewarding one of the state’s critical resources.

The unraveling started with the inept response to the death of University of Maryland football player Jordan McNair. After a brief tug-of-war between campus officials and the University System’s Board of Regents, the latter group took charge and stumbled its way through a process that left everyone perplexed and distressed. Amidst a lot of finger-pointing and backtracking, the board chair resigned, the decision to fire the campus president was rescinded by the board and the football coach was fired after having first been retained.

Neither the full analysis of nor the final reaction to this series of events is in. The General Assembly is in the process of passing legislation that expresses its unhappiness with the board, increasing the amount of transparency required in their decision-making and making a few largely cosmetic changes, but the current bill moving through the legislative process doesn’t really address the basic causes of the mess the board made of the McNair case. Strong willed individuals making decisions in executive session won’t be outlawed.

The Association of Governing Boards, a national higher education association, is in the final stages of its own independent report. The best guess is that the AGB’s findings will be even more critical of the Board of Regents’ action.

But wait, there’s more. And this is where it gets really messy and potentially even more damaging. The chancellor of the University System, Robert Caret, who some–including me–thought was not adequately engaged in the McNair controversy, now finds himself in a contentious battle over accusations that he retaliated against an employee who raised questions about whether he had acted unethically last year. There’s even some question about how the board handled the information about the legal complaint. This matter is now fully public and likely to become even more acrimonious.

The General Assembly has weighed in with budget language cutting $1 million from the Office of the Chancellor. You can see that as a vote of no confidence that won’t easily be reversed. In a second budget provision, the legislature is holding back an additional $200,000 from that budget until the chancellor answers questions about outside income he has received.

Last week it also became public that the board of the University of Maryland Medical System had been allowing its members to engage in business transactions with the medical system. While legislators have started to talk ominously about mandating new conflict of interest rules, Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh, the recipient of what appears to have been a sweetheart deal, has already announced her resignation from the board. Whether this latest controversy actually intersects with the other ones swirling around the University System is not yet clear, but it may get muddled in people’s perceptions regardless.

Clearly there is a lot to sort out here. At this point, it’s hard to see who comes out of this looking good. It may be that there’s less than meets the eye with some of these matters, but there is certainly plenty to be concerned about.

The most significant consequence in the long run is the undermining of public confidence in an important state institution. Someone needs to take on the job of restoring confidence in the governance of public higher education and the effort needs to be much more substantial than a press release or a set of promises. The legislature can ask questions and give the matter a high level of visibility, but that’s not enough.

For reasons that are not readily apparent, Governor Hogan showed relatively little interest in engaging on these critical matters until speaking out publicly about the medical system board. Perhaps he is too busy pursuing the charade that he will challenge Donald Trump for the Republican presidential nomination in 2020, but he’s neglecting important work back here at home. He appoints the members of the Board of Regents and needs to insist that they get their act together.

There are lots of significant details to resolve, but what we are discussing is basically a failure of leadership by the Board of Regents, the chancellor and the governor. The stakes are too high to keep sleepwalking through a series of problems that are being transformed into a crisis.

— Laslo Boyd

The writer, a former acting state higher education commissioner, is a political columnist and higher education consultant.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution