State Supreme Court posthumously honors Edward Garrison Draper, the state’s first Black lawyer

The Supreme Court of Maryland honored the state’s first Black lawyer posthumously Thursday at a special session in Annapolis, the first time ever by the court.

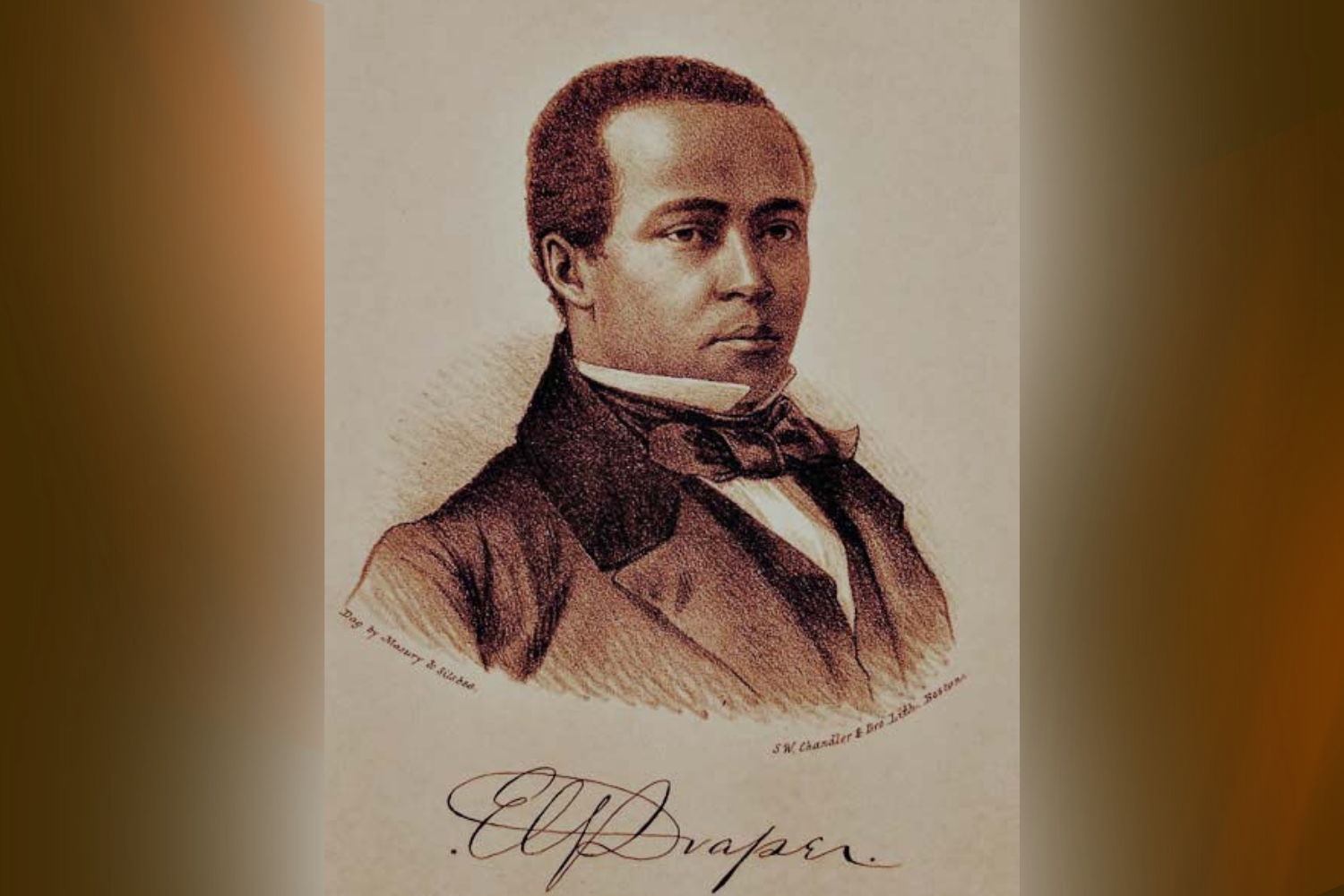

Edward Garrison Draper was born in Baltimore in 1834 and received a law degree in 1855 at Dartmouth College, the Ivy League school in New Hampshire.

According to a law review paper written by retired Texas Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge John G. Browning, Draper petitioned to be admitted in the Maryland State Bar Association on Oct. 29, 1857.

Because Black people weren’t allowed to practice law during that time, Draper was going to emigrate to what is now Liberia. About 100 other Black Marylanders traveled to that country which became known as the “Independent Republic of Maryland.”

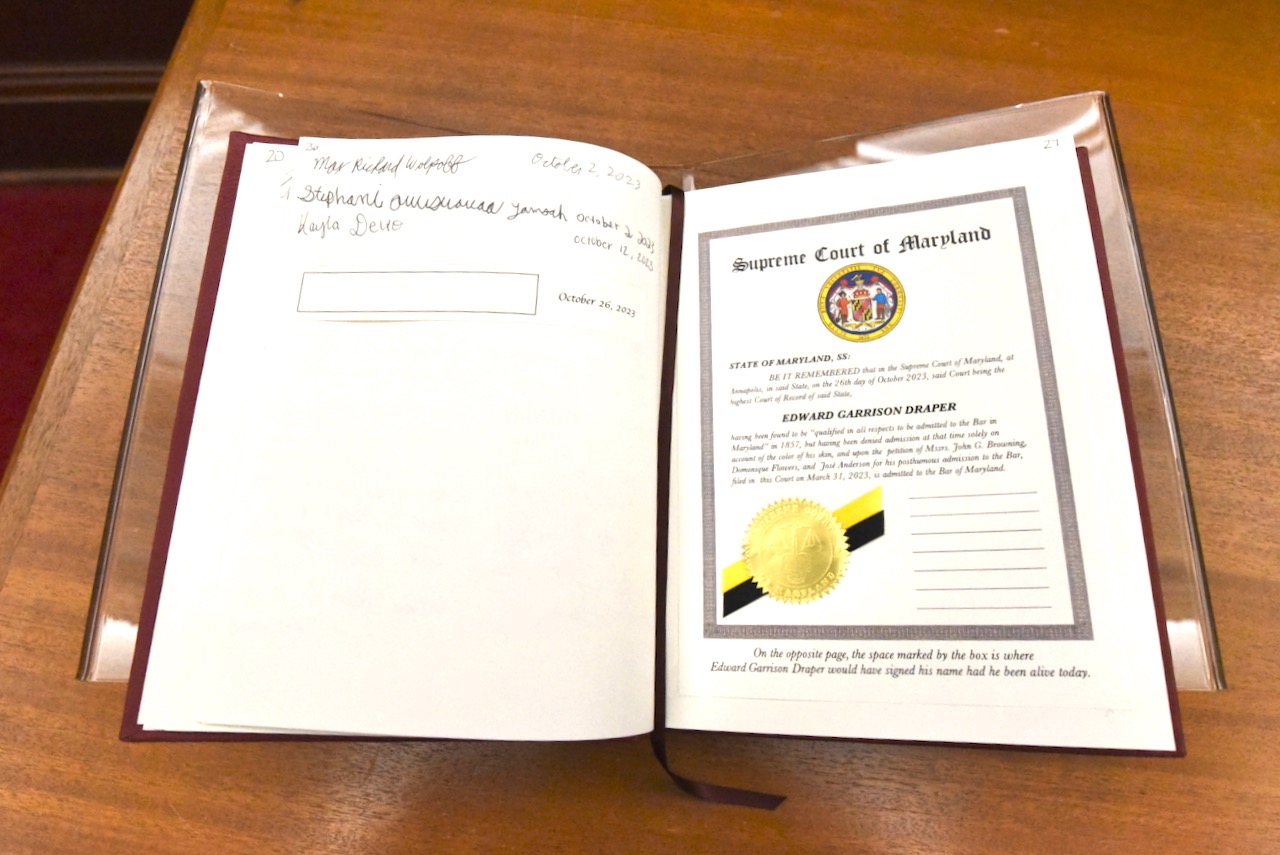

Dominique A. Flowers, Jose F. Anderson, Clerk P. Gregory Hilton and John G. Browning hold a certificate marking Edward Garrison Draper’s posthumous admittance to the Maryland state bar. Photo by William J. Ford.

Browning wrote that Draper petitioned to become admitted to the bar before Baltimore Superior Court Judge Zacchaeus Collins Lee, a first cousin to Robert E. Lee and slave owner, who served as the U.S. District Attorney in Baltimore.

While Lee did not grant Draper admission to the bar, which would have been illegal, he was persuaded to issue the young lawyer a certificate that stated, in part, that Draper was “qualified in all aspects to be admitted to the Bar in Maryland, if he was a free white citizen of this state. This certificate is therefore furnished to him by me, and with a view to promote his establishment and success in Liberia at the Bar there.”

Besides being Maryland’s first Black lawyer, Browning wrote that Draper may have been the state’s first Black college graduate.

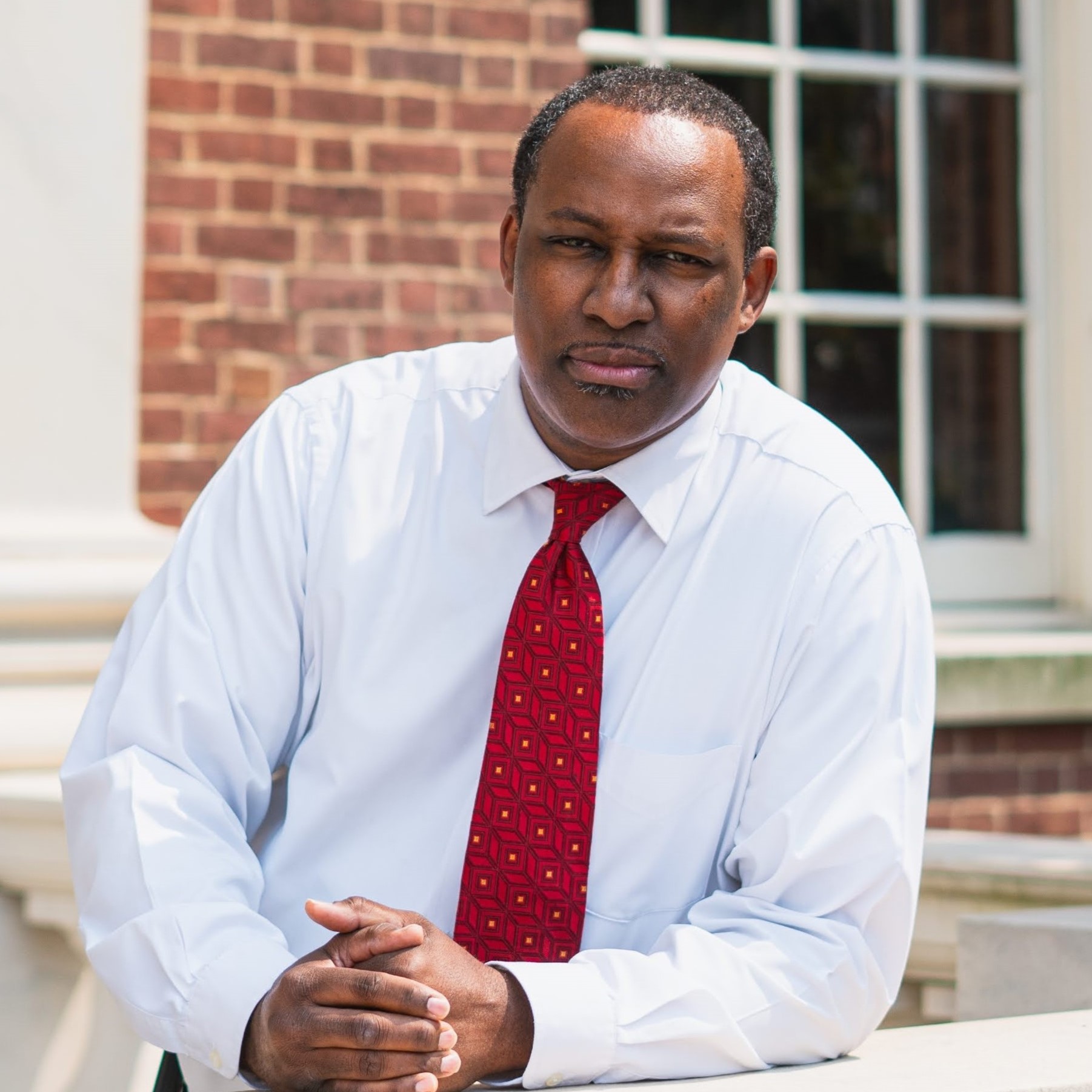

Browning, Maryland attorney Domonique A. Flowers and José F. Anderson, a law professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law, filed a petition for Draper’s posthumous admission to the bar with the state’s Supreme Court on March 27, 2023.

All three attended Thursday’s special session.

Flowers recited the attorney’s oath on behalf of Draper. After they posed for pictures with Draper’s bar certificate, Anderson said, “I am proud to call myself a Marylander. I am proud to call myself a Maryland lawyer. God Bless Maryland.”

Browning said Draper represents the seventh person to be granted posthumous admission to a state bar.

“Now the cynical among us may question the value in granting the relief sought and posthumously admitting Mr. Draper to the Maryland bar,” he said. But “justice delayed may not be justice denied.”

The judge’s law review article, “To Fight the Battle, First you need Warriors: Edward Garrison Draper, Everett Waring, and the Quest for Maryland’s First Black Lawyer,” was published in Fall 2022 by the University of Baltimore School of Law Forum.

Although there are thousands of Black lawyers in the nation who practice law today, the percentage remains low.

According to an American Bar Association report published last year, about 4.5% of lawyers in the U.S. were Black, compared to about 13% of the overall population. In comparison, about 81% of lawyers were white, but whites account for 60% of the nation’s population.

Maryland has the second-highest concentration of lawyers among states, according to the association, with 6.6 lawyers per 1,000 residents.

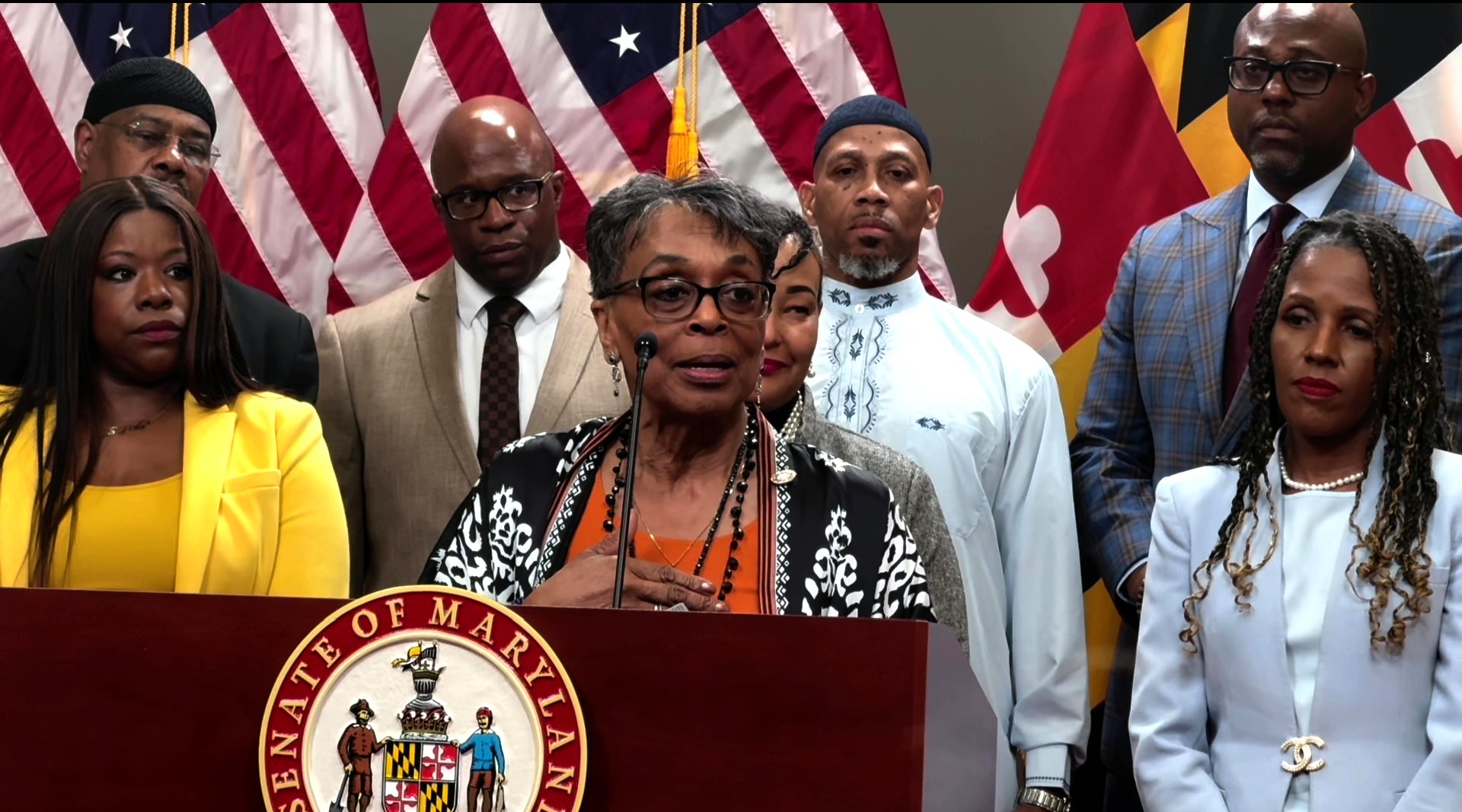

“When the legal professional reflects the diverse fabric of our society it is better equipped to address the needs of all its members,” said Attorney General Anthony Brown (D). “Justice Thurgood Marshall once said, ‘The legal profession is one of the most honorable.’ He said, ‘No one can deny it. It plays a vital role in the preservation of society.’ Mr. Draper understood the significance of the legal profession in shaping our society and championing justice.”

The National Black Lawyers Top 100 lists 53 members who are attorneys in Maryland including William “Billy” Murphy Jr., who manages his own firm in Baltimore. Murphy and his partners have resolved settlements in high-profile cases in Prince George’s County, Baltimore, and elsewhere.

Del. Malcolm Ruff (D-Baltimore), an associate attorney who has worked at Murphy’s firm since 2018, is one of several Black lawyers who are members of the Maryland General Assembly.

“It’s a very unique position to be granted as an attorney, a moniker of being an officer of the court. But being an attorney drives me to work for the people,” Ruff, 39, said in an interview. “Without attorneys zealously advocating for their clients and giving them stellar, outstanding representation, justice would be delayed and denied even more regularly than it already is.”

Ruff said he understands if some people of color believe the law doesn’t support them, but he has a different outlook.

“If you’re not using your personal power to affect the way that the laws of the state and this country operate, then you are really complaining and if you’re not a part of the solution, you’re a part of the problem,” he said. “We have so much political power especially in Maryland. Our leadership is primarily African American…who understand Black issues and how, historically, Black people have been treated under the law. We have a promise from our governor that we are not about picking winners and losers anymore. This is about figuring out how to make the law work for everyone.”

Del. Bernice Mireku-North (D-Montgomery), who manages a general law practice in her county, credits her law school education at Howard University for her being able “to master the law.” Flowers, who helped petition the Supreme Court to honor Draper, also graduated from Howard Law School.

“Those who think the laws are unfair, law school’s the way to go,” she said. “The best lawyers that know the law have that fire [and] see an injustice, whether it’s criminal, whether it’s family law, whether it’s contracts. Master it and do everything you can to get the tools to go back and try and fix [injustices]. Those are the best lawyers that I’ve seen.”

‘Righting the wrong’

Although Maryland is now home to Black elected officials and the largest legislative Black caucus in the country, it took decades to accept any form of integration.

Browning’s paper detailed barriers to civic and business participation by Black residents in Maryland, used, in part, to make leaving the state more enticing to Black residents than staying. One such law was an 1832 statute that required any Black or mixed race person who wanted to sell tobacco, crops or other goods, to get a certificate from a justice of the peace or support from three “respected persons” from their neighborhood who believed the retailer “came honestly and bona fide into possession of any such article so offered for sale.”

Despite the law, Draper’s father, Garrison Draper, became a successful Baltimore tobbaconist and cigar maker.

His wife, Charlotte Draper, who was also a freed Black person, gave birth to their son in January 1834.

To boost Edward Garrison’s Draper’s education, his father sent him to a public school for Black children in Philadelphia.

Because “of a fine preparatory education” in Philadelphia, Draper passed Dartmouth’s college entrance exam in 1851. It encompassed Greek, Latin, English grammar, mathematics and geography.

When Draper graduated from Dartmouth in 1855, the nation had just a handful of law schools. None were in Maryland.

Draper knew of the few Black lawyers — Macon Allen, John Mercer Langston, Robert Morris and George Vachon — who practiced law in the United States.

Draper was mentored by retired Baltimore attorney Charles Gilman, a member of the Maryland Colonization Society’s Board of Managers.

A certificate acknowledging the posthumous bar admission of Edward Garrison Draper was on display in Maryland on Thursday. Photo from the Executive Office of the Governor.

Draper also was tutored by Charles W. Storey, a prominent Boston attorney who studied in the law offices of George T. Curtis. Curtis was part of the legal team that worked on the Dred Scott case heard in the U.S. Supreme Court. It was ruled in March 1857 that Scott and other Black students in the state of Missouri weren’t entitled to their freedom.

About seven months later, in October 1857, Draper went before the Baltimore judge and received the certificate vouching for his ability to practice law in Liberia.

Six days after the judge’s decision, Draper and his wife, Jane Rebecca Jordan, left Baltimore on their voyage to Liberia.

Draper’s legal career didn’t last long because he died in December 1858, about two weeks before turning 25 years old.

“Nothing is known of Draper’s all too brief legal career in Liberia. What we do know is that, but for the color of his skin, this Ivy League graduate met all the requirements for admission to the Maryland bar,” Browning wrote. “Edward Garrison Draper deserves to be added to the small but growing number of members of diverse communities who have been granted posthumous bar admission by state supreme courts in the 21st century, as a way of righting the wrong of being rejected by the bar on racial grounds during the 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Nearly three decades later, the first Black lawyer admitted to the bar in Maryland was Everett Waring on Oct. 10, 1885. Several Southern states admitted Black lawyers to the bar before Maryland including: Arkansas in 1866; Tennessee and South Carolina in 1868; Mississippi in 1869; Alabama, Louisiana and Virginia in 1871; Texas in 1873; and Georgia in 1878.

Although it took 166 years for Edward Garrison Draper to be admitted to the Maryland bar, Justice Angela M. Eaves of the Supreme Court of Maryland said: “The time for settling this matter is now. There is no expiration to do the right thing.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution