Legislative workgroup reviews Maryland Higher Education Commission’s strategic plan and those of other states

A legislative workgroup created to assess Maryland Higher Education Commission policies for approving new academic programs convened for a third time Wednesday, but has less than six weeks to complete its work.

Called the Program Approval Process Workgroup, it is co-chaired by Sen. Nancy King (D-Montgomery) and Del. Stephanie Smith (D-Baltimore) and it heard presentations on the commission’s higher education plan and overviews of plans from other states.

Emily Dow, assistant secretary of academic affairs for the commission, said Maryland’s plan was last updated in June 2022. That 73-page plan highlighted the 10 key industries that the Maryland Department of Commerce projects will help boost the state’s economy.

New to the department’s list are quantum computing, cleantech and renewable energy and data centers and advanced manufacturing/industry 4.0. Those join advanced manufacturing, aerospace and defense; agribusiness; life sciences; cybersecurity and IT; distribution and logistics; energy and sustainability; financial services; military and federal; and tourism.

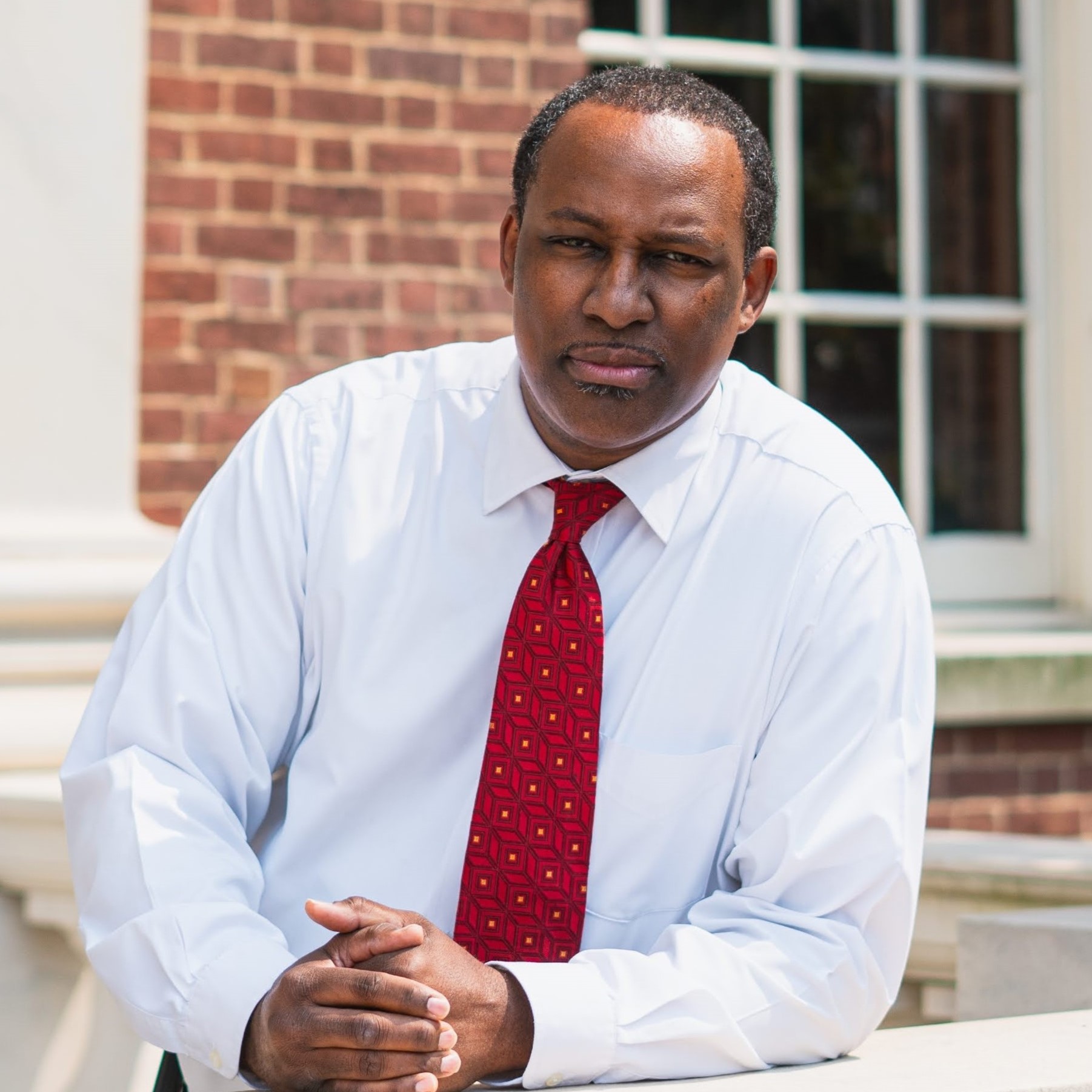

Pace McConkie, director of Morgan State University’s Robert M. Bell Center for Civil Rights in Education and a member of the workgroup, asked how the commission determines if an institution meets the state’s higher education needs in providing enough capacity and meeting job market demands.

Dow said some institutions “are cautious” about specifying their capacity in order to have some leeway for future expansion. Capacity could mean expansion of a building to house more students and staff, or being able to offer additional academic programs.

“Does that mean an institution could be denied a program because they’ve been identified as not having capacity to do a particular thing? There’s nuance there,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean there is an opportunity to do that work better or with more specificity. I think you’re showing our agency’s underbelly a little bit here.”

Ben Erwin, senior policy analyst with the Denver-based Education Commission of the States, assessed 17 states with a higher education plan and an agency similar to Maryland’s.

But some states’ systems of higher education organize their plans and assess their needs differently.

In North Carolina, the university and community college systems approved separate strategic higher education plans last year.

The Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education announced in February it will create an online “user-friendly credential registry” for students in two-year and four-year colleges and for workers to assess what education and professional credentials exist and which best suit them.

The state of Washington’s Board for Community and Technical Colleges approved a 10-year plan in June that is scheduled to guide the college’s system through 2030.

Erwin said identifying and defining appropriate fields of study and job market needs in a particular state involves “usually politically fraught conversations with a lot of different components that go into those decisions.”

‘Unnecessary program duplication’

The workgroup’s nearly one-hour session didn’t review some reform proposals from Maryland HBCU Advocates, a coalition of supporters and alumni from the state’s four historically Black colleges and universities – Bowie State, Coppin State, Morgan State and University of Maryland Eastern Shore. The group emailed several recommendations to the workgroup Monday.

One recommendation is to amend the commission’s current policy on program duplication because the commission “is obligated to bear in mind Maryland’s ongoing legal commitment to end definitely its long history of unnecessary program duplication within its system of higher education.”

Part of that recommendation focuses on the 2006 lawsuit that the advocates filed arguing that the state historically provided more resources for predominately white institutions and allowed duplication of programs already offered by the state’s HBCUs. Former Gov. Larry Hogan (R) signed legislation two years ago that authorized a $577 million settlement of that claim.

The HBCU advocates also suggest creating an advisory committee to help assess program duplication protests and that the committee should include members of the advocacy group and others in the higher education community who “may make recommendations to the Commission on matters of statewide importance that affect their constituencies.”

The workgroup meets again Nov. 7 and must complete a report with recommendations by Dec. 1.

HBCU advocates, some state lawmakers and higher education officials have criticized the Maryland Higher Education Commission’s approval of some new academic programs.

This summer, Morgan State University President David K. Wilson said a proposed business analytics doctoral program from Towson University would duplicate an existing doctoral business administration program at Morgan State.

In June, the commission voted 4-3 to approve Towson’s plan.

A month later, Gov. Wes Moore (D) appointed seven new people to serve on the 12-member commission and the Office of the Attorney General advised said the vote was of “no legal effect” because it lacked a majority.

In August, Towson withdrew its plan after the commission requested that institutions “pause” new degree proposals if an objection is raised by another college or university. However, they are not required to do so.

In the same month, Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore submitted a proposal to establish a new bachelor’s degree in nursing in partnership with Mercy Medical Center and Mercy Health Services Inc.

According to an Aug. 15 letter from Loyola provost Cheryl Moore-Thomas, a “critical nursing shortage” remains in the state and the nation.

Notre Dame of Maryland University, located near Loyola, objects to the plan because it would cause “unreasonable program duplication which would cause demonstrable harm” to its institution.

Martha Walker, provost for Notre Dame, acknowledged in a Sept. 26 letter that there are nursing shortages throughout the state. However, Walker said that Loyola’s plan “does not meaningfully address how they plan to recruit and hire nurse educators amidst a national and State faculty shortage.”

In response to Notre Dame, Moore-Thomas wrote, in a Oct. 16 letter to Acting Secretary of Higher Education Sanjay Rai, that eight other institutions with nursing programs in the vicinity of both schools didn’t object to Loyola’s proposal.

Both are private, religious schools in the city. Loyola has a Jesuit education mission and Notre Dame is centered on the Catholic faith.

The commission is scheduled to meet Wednesday, but the agenda doesn’t note that Loyola’s program will be discussed.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution