First Amendment advocates fight growing number of book bans

One of Thomasina Brown’s favorite books is a memoir about a girl who deals with the grief of losing her father and struggles with her sexual identity.

Brown, a 16-year-old student at Nixa High School in Nixa, Missouri, said in an interview that she felt a connection with the book, as she grieved the loss of her own father and came to terms with her own queer identity.

That book, “Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic,” is one of the more than 3,300 books that have been banned during the 2022-2023 school year, a 33% increase from the previous school year, according to a report by PEN America, a group that is dedicated to fighting book bans and advocates for the First Amendment.

“I saw myself very much so reflected in those pages,” Brown said of the book by Alison Bechdel that the Nixa school board banned. “And so for adults and the school board to deem it inappropriate felt kind of like they were telling me I was inappropriate, and I don’t think that’s fair.”

In the last few years, there has been an unprecedented wave of book bans and censorship spurred by parents and conservative groups to target books that center the LGBTQ+ community, Black history and diverse stories. During the 2022–23 school year, book bans occurred in 153 districts across 33 states, according to the PEN America report.

Many of the book bans started during the early days of the pandemic, part of frustration over mask mandates and online learning that eventually led to the politicization of school board meetings.

To combat this, and in celebration of Banned Books Week on Oct. 1-7, PEN America has launched online training for students to fight book bans, and more recently, teamed up with bestselling authors to fight against book bans across the country.

Some of those authors include Judy Blume, Ruby Bridges, Suzanne Collins, Michael Connelly, Gillian Flynn, Amanda Gorman, Nikki Grimes, Daniel Handler, Khaled Hosseini, Casey McQuiston, James Patterson, Jodi Picoult and Nora Roberts, among others.

Although the PEN America report notes Maryland was one of 17 states without book bans, there has been some local resistance.

A U.S. District judge ruled against a preliminary injunction sought in August by three Montgomery County families, who want to immediately opt their children out of classroom discussions when books mention LGBTQ+ characters. The families claim the county school board’s no opt-out policy violates their and their children’s rights.

The broader legal challenge remains pending in court.

Further north in Carroll County public schools, officials pulled nearly six dozen books off shelves for a reconsideration committee to review, a process that is ongoing.

Other smaller-scale challenges have popped up around the state as part of the national effort.

State and federal actions

Beyond local school boards, Republican lawmakers at the state level have also joined the movement to ban books from public schools and libraries.

And the Republican-majority U.S. House this year passed legislation known as a Parents Bill of Rights. Democrats criticized the bill, arguing that it would lead to book bans.

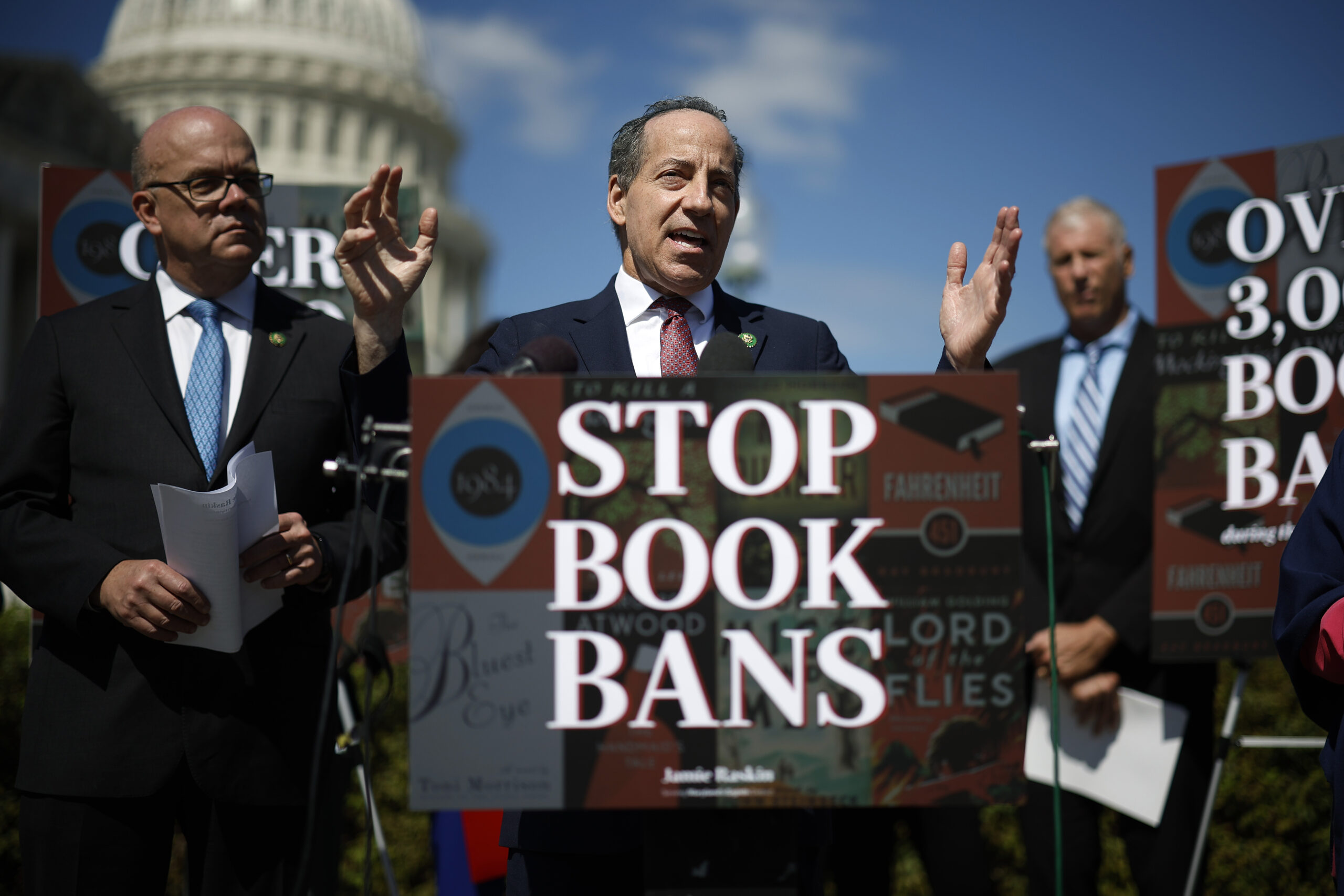

Congressional Democrats have raised concerns about the increase in book bans across the country. U.S. Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-8th) and Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) introduced a resolution to recognize Banned Book Week and condemn bans on books.

“The escalating crisis of book bans across our country in recent years is a direct attack on First Amendment rights and should concern everyone who believes freedom of expression and the freedom to read are essential for a strong democracy,” Raskin said in a statement. “The sinister efforts to remove books from our schools and libraries are a hallmark of authoritarian regimes.”

In September, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing to discuss the consequences of book bans, but senators ultimately decided it was not Congress’ role to intervene.

The White House in June announced that the Department of Education Office for Civil Rights would appoint a coordinator to counter the massive wave of book bans across the country.

However, the department has not responded to multiple requests from States Newsroom asking about the hiring status of the new coordinator.

One state, Illinois, became the first state to pass a law outlawing the banning of books.

Eight states home to a majority of bans

PEN America found that 87% of the book bans were in school districts with a nearby chapter or affiliate of a national group known for advocating for book banning or censorship.

And 63% of all book bans, or 2,114 books, occurred in eight states — Florida, Missouri, Utah, Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Oklahoma and West Virginia — with state laws that either banned books or created local pressure to remove books for the 2022-2023 school year.

Two states have also recently passed similar legislation, Texas and Iowa.

The main group that has challenged school boards is Moms for Liberty, an organization formed in 2021 that has strong GOP ties and local chapters that “target local school board meetings, school board members, administrators, and teachers” to push right-wing policies, as reported by Media Matters. Moms for Liberty has about 300 chapters across 47 states.

Moms for Liberty has four chapters in Thomasina Brown’s home state, but not in her town of Nixa. There is a chapter right next to the county she lives in, which is Christian County.

Brown said that many of the book challenges came from faith-based groups.

Brown, who runs a club with several other students to push back against book bans, often attends school board meetings where books she’s read are being challenged.

“We’re telling this group of adults, how these things directly impact us,” she said. “They’re the books that we read in our schools, in our libraries. We’re telling them our stories, our identities, and they’re telling us that it’s inappropriate, and we don’t know what’s best for ourselves, even though some of us that get up there and talk are 18 and are able to vote on these issues and definitely can have a say in what they can be reading.”

She said she feels sad when she attends those school board meetings. When a book is banned, there are typically cheers from adults in the audience, she said.

“That was really disheartening,” she said. “I just watched my peers get up and share their experiences and why the books and our schools and our libraries were important to them and important to other students, and we were basically completely ignored.”

But Brown said she is still fighting. Even though it’s her senior year, she’s spending time training a sophomore to take over the club, Nixa Students Against Book Restrictions. She said she understands the importance of books.

“Being able to read stories from different perspectives, I think really is able to build a lot of empathy for what other people go through or what they have gone through in the past, and I think that’s really important,” she said.

Challenging books in Carroll County

In Carroll County, the 12-member reconsideration committee will review five books at a time and recommend whether the school board should remove or keep them in the schools.

The committee already reviewed and rejected the challenges to five books in high school libraries: “Not That Bad: Dispatches From Rape Culture,” “The Perks of Being a Wallflower,” “Slaughterhouse Five,” “The Sun and Her Flowers,” and “Tilt.”

School system spokesperson Carey Gaddis wrote in an email last week that four of the books, with the exception of “Slaughterhouse Five,” require parental approval to check out for students 17 and younger.

The committee recommendation can be appealed to the school superintendent and subsequently to the county board of education.

People supporting and opposing the book challenges turned out in numbers to a school board meeting in September.

The board’s next meeting is Oct. 11.

The requests to review the dozens of books came from the Carroll County Chapter of Moms for Liberty.

Jessica Garland, vice chair of the chapter, wrote in an email that the challenges focused on books that contain sexually explicit content.

“Our reconsideration requests did not discriminate between heterosexual or homosexual characters,” Garland wrote. “If it was graphic and sexually explicit, [then] it was submitted for reconsideration regardless of the gender or race of the characters.”

But several of the books being challenged were written by LGBTQ+ authors or writers of color.

“Those books are overwhelmingly swept up in this larger rhetoric around removing books,” said Kasey Meehan, the Freedom to Read program director at PEN America. “School is a place that has always been grounded in information sharing and knowledge building, increasing awareness to offer…empathy and understanding of our pluralistic society.”

Fighting book bans in Florida

One of the frequently banned authors, Michael Connelly, has committed $1 million to launch PEN America’s efforts in Florida, where the organization plans to open a Florida center before the end of the year to host public events and spearhead campaigns against book bans.

“We see Florida as almost setting the map for where other states could go and certainly we hope that efforts to oppose book bans in Florida will also help us in how we think about pushing back against book bans before they ramp up to this scale in other states,” Meehan said.

For the 2022-23 school year, more than 40% of book bans occurred in Florida, with 1,406 book bans in the state. States with high numbers of book bans include Texas with 625; Missouri with 333; Utah with 281; and Pennsylvania with 186.

In Florida, during the 2022-23 school year, 33 out of 69 school districts have book bans, nearly half of all school districts in the state, Meehan said.

“When we look at Florida, and Florida appears to be such an anomaly, what’s important for PEN and for other organizations that are tracking these movements is that Florida isn’t necessarily an outlier. They are putting forth the roadmap for other states to follow,” Meehan said.

PEN America and publishing giant Penguin Random House also sued a Florida school district in May over the school board’s decision to remove books about race and LGBTQ+ identities.

States and the number of books they have banned from July 2022 – June 2023 include:

Arkansas, 4 books

California, 1 book

Colorado, 8 books

Florida, 1,406 books

Georgia, 4 books

Idaho, 25 books

Indiana, 3 books

Iowa, 6 books

Kansas, 7 books

Kentucky, 3 books

Maine, 13 books

Massachusetts, 1 book

Michigan, 39 books

Minnesota, 1 book

Missouri, 333 books

Nebraska, 6 books

New Hampshire, 1 book

New Jersey, 3 books

New York, 6 books

North Carolina, 58 books

North Dakota, 27 books

Oklahoma, 2 books

Oregon, 38 books

Pennsylvania, 186 books

South Carolina, 127 books

South Dakota, 2 books

Tennessee, 11 books

Texas, 625 books

Utah, 281 books

Virginia, 75 books

West Virginia, 2 books

Wisconsin, 43 books

Wyoming, 15 books

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution