Lawmakers view state climate ‘pathway’ recommendations through parochial lenses

For the last several weeks, Maryland environmental officials have taken their draft plan for meeting the state’s weighty climate goals on the road, with three public hearings and more to come. On Tuesday, in a 90-minute virtual session, they took feedback from an immensely important constituency: state and local policymakers.

At least two dozen state and local lawmakers were among more than 100 people who dialed in to the Maryland Department of the Environment’s afternoon session, and about a dozen state legislators asked questions. Chris Hoagland, director of the department’s air and radiation program, who is leading the effort to put together an aggressive climate implementation plan, said the lawmaker feedback would become part of the agency’s final report, which is due out in December.

“We’re keenly interested in the input from the elected leaders,” he said.

At least a few things emerged during the virtual session. One is that, with a few wonky exceptions, lawmakers are viewing the Department of the Environment’s plan to meet state climate goals largely through parochial lenses. And they are already wondering about how to sell it to their voters.

“This final report needs to reassure people that their lives are not going to be upended between now and 2031,” said Sen.Chris West (R-Baltimore County).

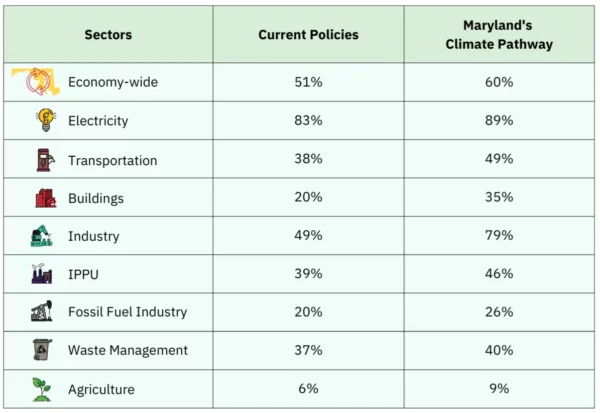

2031 is when the state is required to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 60%. The 2022 Climate Solutions Now Act requires Maryland to try to hit net-zero carbon emissions by 2045.

If Tuesday’s hearing is any guide, it’s also apparent that state legislators will feel more comfortable digesting the Department of the Environment’s draft report when it’s a more polished document in December. That plan is likely to result in legislation that will be debated in the 2024 General Assembly session and possibly beyond.

Right now, the document is a series of broad recommendations for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by sector, but steers clear of hard-and-fast policy prescriptions. It was put together by the University of Maryland’s Center for Global Sustainability, using economic modeling from the Towson University Regional Economic Studies Institute.

Maryland’s climate effort comes as the federal government, through the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, is seeking to provide billions of dollars in funding to state and local governments to combat climate change. The Biden administration goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. by 40% by 2030, Alison Riley, a policy specialist with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, told lawmakers on Tuesday’s call.

Riley said EPA is making $41 billion available to the states, plus an additional $11.7 billion thanks to a tax reinstated on oil and gas companies to help pay for Superfund site remediation. More government funding is available from the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Transportation, she said.

“This is the biggest, broadest effort we’ve ever made toward addressing climate change,” Riley said. “The idea here is, we want to tackle emissions in as many ways as possible.”

Del. Regina T. Boyce (D-Baltimore), the vice chair of the House Environment and Transportation Committee, asked how Maryland was doing when it came to applying for federal grants. Hoagland said Maryland was the very first in the nation to apply for a planning grant from EPA, which will soon enable the state to pursue more federal funding.

Even so, Del. Dana M. Stein (D-Baltimore County) fretted that too few government agencies and institutions in Maryland are making the public and private organizations aware that they may be eligible for federal assistance.

“Right now I think there’s very little understanding of all the help and benefits,” he said.

And speaking of the federal government, Del. Sheila Ruth (D-Baltimore County) wondered how the Biden administration’s expected push to get government workers back into their offices could affect the state’s efforts to reduce vehicle commutes and emissions.

Lawmakers also asked a range of questions based on their professional and geographical interests. Del. Linda M. Foley (D-Montgomery), who represents a suburban district, asked whether the state plan seeks emission reductions from noisy leaf blowers and lawn mowers. Hoagland replied that the draft plan doesn’t directly address it, but said it’s possible that the final document could.

Del. Jared Solomon (D-Montgomery), whose district is partially suburban but also takes in downtown Wheaton and a piece of downtown Silver Spring, asked about the interplay between transit-oriented development projects, efforts to boost transit service in the state, and climate goals.

Sen. Mike McKay (R-Allegany) worried that the climate plan would target propane, a common source of heating in Western Maryland, and also pointed out that the climate in the state’s most mountainous regions is dramatically different than it is in most of the rest of Maryland.

“As we come up with the climate pathway, we have to make sure that Western Maryland isn’t left behind or redlined, the way it’s been with Appalachia in the past,” he said. “We just need to remember what the governor said — that no part of Maryland is to be left behind.”

Sen. Jason C. Gallion (R-Harford), the lone full-time farmer in the General Assembly, asked several questions about the climate plan’s potential impact on the agriculture industry. Hoagland noted that many farmers are already using practices that are helping the environment — an assertion that Gallion, a cattle farmer, appreciated. But because, as he pointed out, “cattle flatulence” contributes greatly to greenhouse gas emissions, he wondered if a state climate plan might require cattle and dairy farmers to reduce their herds.

Kathleen Kennedy, the chief author of the Department of Environment’s preliminary report, said that based on “EPA’s marginal abatement cost curves,” that should not be an issue. “You’re not changing the herd, you’re just managing it differently,” she said.

It was left to Del. Lorig Charkoudian (D-Montgomery), a lawmaker who regularly goes deep into the weeds on energy and climate policy, to sound a note of caution about some preliminary numbers contained in the document. Agency officials believe the state is already 51% toward meeting its 2031 climate goals, but Charkoudian suggested that several assumptions about carbon reductions could be overly optimistic.

“We’re behind on [expanding] rooftop solar, we’re behind on utility-scale [solar],” she said. “I could go on with all the things I think could go wrong with the 51%…Frankly, I think we need to be padding our proposal with more [clean energy and emissions reductions], because I don’t think we’re going to hit 51%.”

Hoagland did not push back.

“We’re considering how to address that in a final plan,” he said.

The next public hearings on the draft proposal are scheduled for Sept. 12 at 6 p.m. at Morgan State University in Baltimore and on Sept. 19 at 6 p.m. at the College of Southern Maryland in Prince Frederick. A final online hearing is scheduled for Sept. 26 at 6 p.m.

For more information, go to www.mde.maryland.gov/climatechange.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution