Juvenile Justice Bill Seeks to Address Failures of Many Systems

Squirting juice at a crush.

Breaking a window playing basketball.

Drawing on a friend’s coat at school.

Stealing a bag of chips from the cafeteria.

Riding a bike someone left in the yard.

These are offenses that can lead a preteen to court.

“Quite often as public defenders, we represent kids who are very young being prosecuted for acting like kids,” Michal Gross, an assistant public defender, told the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee during a bill hearing on Thursday.

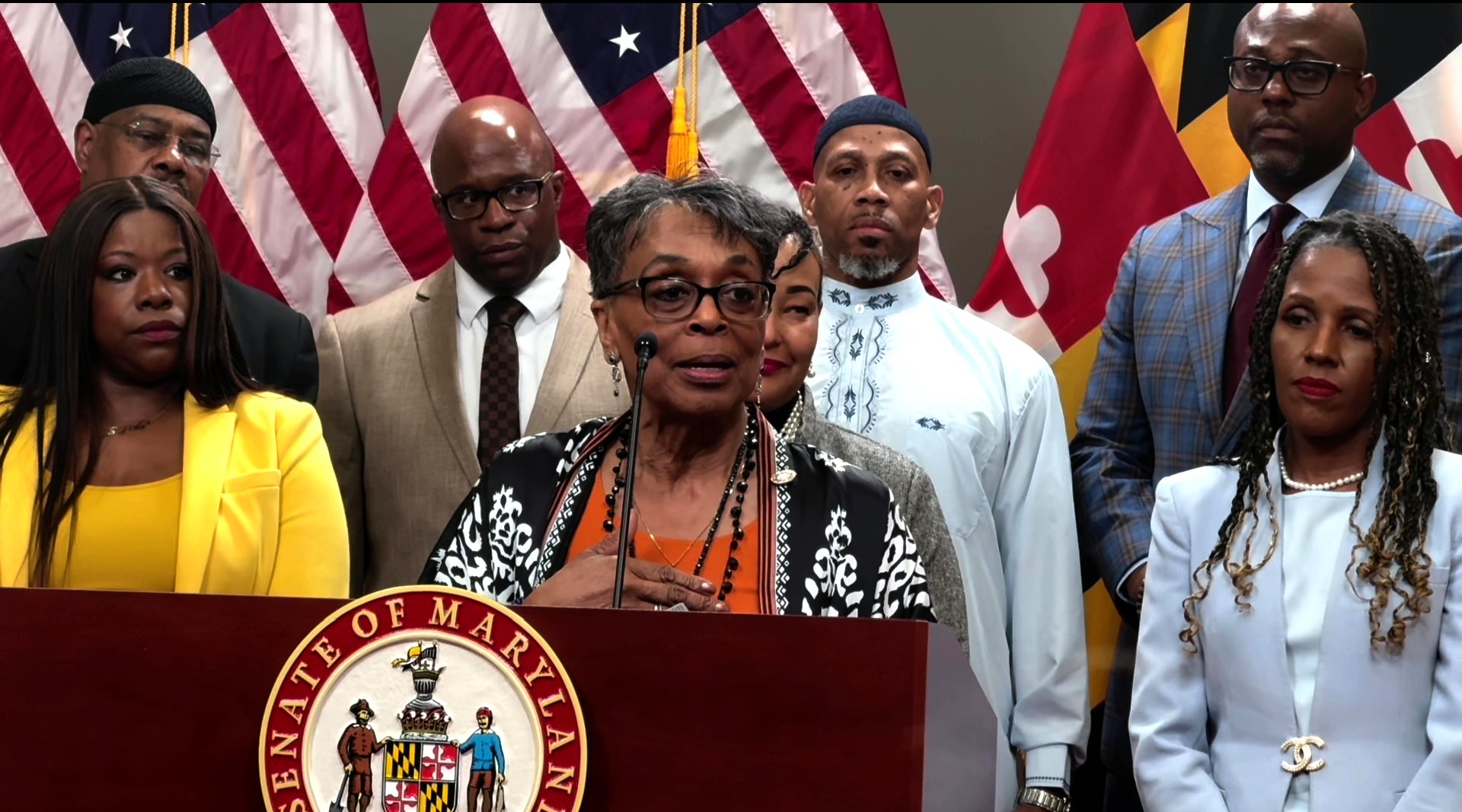

An omnibus juvenile justice reform bill sponsored by Sen. Jill P. Carter (D-Baltimore City) seeks to stop charging children for petty crimes and focus resources on kids who are in need of intervention services.

“Children are different than adults,” Carter said Thursday. “Despite this obvious truth, in our juvenile justice system, they are treated as if they are small adults.”

Senate Bill 691 is based on recommendations of the bipartisan Juvenile Justice Reform Council, which was comprised of lawmakers, advocates, prosecutors, public defenders and victim advocates who were appointed to study public safety and youth justice practices.

The legislation would generally prohibit kids under 13 from facing criminal charges, though charges could be placed in criminal court for the most serious crimes, including murder and sexual offenses. The bill would also set limitations on terms of detention, out-of-home placement and probation that can be imposed by juvenile courts.

According to Carter, in 2020 about 1,500 delinquency complaints were filed against children younger than 13 and 71.5% of them were Black.

Marc Schindler, executive director of the Justice Policy Institute, said that Black and Brown children often receive harsher sentences than white children get for the same offenses. He called the racial disparities in Maryland’s juvenile justice system “alarming.”

Sen. Robert G. Cassilly (R-Harford) asked Schindler what caused racial disparities in the system.

“Are those caused by racism within the juvenile justice system? I mean, is the secretary racist, are the judges racist?” he asked. “Or is this some other innate characteristic of the African American community that we’re seeing? Are there challenges that are not because of racism within the system but because of other aspects?”

Schindler responded that he thinks the problem lies beyond Maryland’s justice system and includes institutional racism in housing, education and the workforce, and the copious amounts of money spent on incarcerating Black and Brown communities.

He also acknowledged that leaders and decision-makers are not immune from implicit bias.

“All of those issues tend to come together and create more challenging environments — more challenging situations — for communities of color,” he said.

Cassilly said he wants to understand the root of the problem because not every kid in underfunded schools or poor neighborhoods ends up in the juvenile justice system.

Some are more resilient, Schindler said, noting that most kids go through adversity and bounce back.

“But we do know there are risk factors,” he said. “And when they accumulate — whether that’s educational disabilities, whether that’s poverty… — these are risk factors that, the more you have, the more likely it is that you’ll end up being referred to the justice system.”

Panelists testifying in favor of the bill said that kids may end up in the Department of Juvenile Services because of the failings of other state-run systems.

Carter said she remembers reading document after document about the dangers that lead poisoning poses to young brains.

According to Carter, children with serious exposure to lead are approximately six times more likely to have a brush with the juvenile justice system.

“So when we talk about systemic racism, I would just point out that our failure to do the adequate things to address lead poisoning likely are a contributing factor,” Carter said.

In an interview after the Thursday bill hearing, Juvenile Public Defender Jenny Egan said policymakers have been using the Department of Juvenile Services “as the outlet for all of our community’s problems,” particularly those that need to be addressed by the state’s Board of Education and Departments of Human Services and Health.

She said legislation like Senate Bill 691 will put an end to the mentality of “when the adult fails the kid goes to jail.”

“The criminal and delinquency system doesn’t have the services that all kids need to successfully transition kids to adulthood,“ Egan said. “You can no longer use cells and cages to address problems in the other child-serving agencies.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution