Civil Rights Advocates Sue After Baltimore County Council Approves Redistricting Plan With Only One Majority-Black District

The Baltimore County Council voted unanimously to approve a redistricting proposal with just one majority Black council district Monday, spurring a lawsuit from civil rights advocates and residents who say the map unlawfully dilutes Black residents’ power.

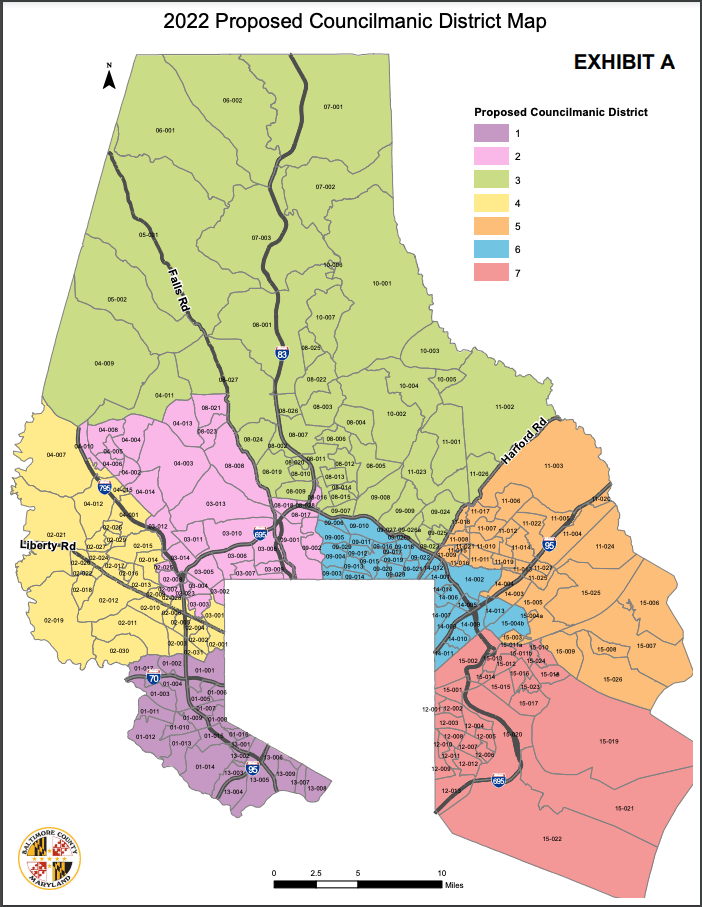

Five of seven districts in the redistricting plan approved by the county council Monday are majority white and another has 46.17% white plurality. Just one district would be majority Black at 72.59%, according to data released by the Baltimore County Council.

Just over 30% of county residents are Black and almost half of county residents are people of color, according to U.S. Census data.

Baltimore County residents and civil rights groups including the Baltimore County NAACP and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Maryland have for months urged county council members to draw a second majority Black district, including at a marathon county council work session last week and at a rally organized by students in Towson Saturday.

Civil rights advocates, residents and some state lawmakers, including Sen. Charles E. Sydnor III (D-Baltimore County) have said the county council’s redistricting plan “packs” Black voters into Jones’ 4th District, violating the federal Voting Rights Act. That federal law bans minority vote dilution by cracking, or “fragmenting the minority voters among several districts where a bloc-voting majority can routinely outvote them,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice, or by “packing them into one or a small number of districts to minimize their influence.”

On Tuesday, the Baltimore County NAACP, Common Cause Maryland and the League of Women Voters of Baltimore County and several Black voters from the county filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court arguing the newly adopted council map violates the Voting Rights Act. Dr. Danita Tolson, president of the Baltimore County NAACP, said in a statement that the groups “have no choice but to seek redress in federal court” to stop the redistricting plan.

An updated Baltimore County Council redistricting plan released mid-November does not include a second majority Black county council district despite calls from advocates and lawmakers. County image.

“By adopting this illegal legislation, the Baltimore County Council joins the ranks of infamous state and local politicians throughout the country who are adopting redistricting legislation designed specifically to solidify their incumbency and disenfranchise African American and other minority voters,” Tolson said in a statement. “It is abundantly clear that the Baltimore County Council’s adopted redistricting legislation will result in continued dilution of African American and minority voting strength.”

The plaintiffs want to see the map struck down in court. Sydnor, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, slammed the redistricting plan in a statement.

“I take no pleasure in having to sue my County government,” Sydnor said. “I have no doubt that its act will have an adverse effect on this entire County for years to come. It pains me that in 2021 we still find ourselves fighting against tactics meant to dilute voices in the political arena. It pains me that today we must sue for something as fundamental and basic as our full right to equally participate in the local governance of our communities.”

Dana Vickers Shelley, the executive director of the ACLU of Maryland and Baltimore County resident, is also a plaintiff in the lawsuit. Vickers Shelley said the redistricting proposal is “in clear violation of the Voting Rights Act.”

“They remain determined to protect their own self interests — their place and positions — above the rights of thousands of Black voters in the County who deserve fair representation,” Vickers Shelley said in a statement. “However comfortable Council members might feel about passing an illegal plan, the Voting Rights Act still exists and Black voters are determined to defend it and our right to have elected officials who represent us and our communities.”

Baltimore County’s current council map has only one majority Black council district, which was drawn in 2001 after a push from civil rights activists. Since that district was drawn, residents of the lone majority Black district have elected a Black council member in every election since it was created, while majority white districts have elected white council members. Baltimore County Council Chair Julian E. Jones Jr. (D) remains the only Black council member.

“I served as President of the Baltimore County Branch of the NAACP in 2001 when we challenged the redistricting map,” Anthony Fugett, a plaintiff and voter in Baltimore County, said in a statement. “The County Council listened to our request and created what is today the 4th District. Now in 2021 the current Council decided not to listen to some of its citizens who requested a map that represented the racial makeup of the County. Instead, they made their reelection the priority for the map. It is a sad day for Baltimore County when a citizen has to take the county you live in to Federal court to do their job.”

While the ACLU of Maryland, the Baltimore County NAACP and various community groups submitted various redistricting plans to the county council that included two majority Black districts, council members argued Monday that it isn’t possible to draw two majority Black council districts without splitting neighborhoods and communities.

“Communities do not want to be divided,” Council member Thomas E. Quirk (D) said at the Monday meeting.

Quirk added that he thinks the map will hold up in court.

“I think this map stands strongly, so I’m not concerned about that,” Quirk said during the meeting.

There are four Democrats and three Republicans on the county council. Jones previously said he believes a second majority Black district would be “justified” based on the county’s population, but said the council’s redistricting proposal represents a configuration that could garner the five votes necessary to pass.

Jones also argued in a recent YouTube video that splitting his 4th District, which will be more than 72% Black under the redistricting plan, to create two districts with smaller majorities wouldn’t guarantee a Black county council member.

“We had different methods and different philosophies and different things that we thought would make Baltimore County stronger, but at the end of the day we have to resolve to agree on a map that has enthusiasm and we can all support,” Council member Israel C. “Izzy” Patoka (D) said Monday.

County Executive John A. Olszewski Jr. (D) said in a statement on Tuesday that he and others “share the concerns of community members.”

“Opportunities for greater minority representation across all districts is vital. Our administration remains focused on doing all we can to promote policies that expand diversity and inclusion across our County,” Olszewski said in a written statement. “We cannot comment further at this time in anticipation of litigation.”

Public campaign finance measure approved

County council members also approved a bill that will create a public campaign financing system in the county, but added expenditure limits to candidates who participate — a measure that fair elections advocates say might disincentivize participation in the program.

That program will feature a tiered funding system that will prioritize smaller donations to candidates who opt to participate. Candidates will have to file a notice of intent to participate in the public financing system, set up a new campaign account and meet the following conditions to participate in the planned program:

- Only accept donations from individuals;

- Only accept donations of $250 or less;

- Refuse donations from political action committees, corporations, political parties and other candidates;

- and candidates would also have to prove their campaign is viable by meeting a minimum threshold of $40,000 in qualifying contributions from at least 500 local donors for county executive candidates and $10,000 in qualifying contributions from at least 125 local donors for county council candidates.

Public matching funds are capped at $750,000 for county executive candidates in a campaign cycle and $80,000 for county council candidates.

Public matching funds will be distributed in a tiered system to prioritize smaller donations: Candidates for county executive would receive $6 for each dollar of the first $50 in a donation, and matching funds would phase out after $150. For a maximum donation of $250, a county executive candidate would receive $600 in matching funds.

Candidates for county council would receive $4 for each dollar of the first $50 of a donation, and matching funds would also phase out after $150. That means a county council candidate would receive $450 in matching funds for a maximum individual donation of $250.

Baltimore County voters approved a charter amendment last November to create a Citizens’ Election Fund system in the county, and the tiered financing system in the bill is based on recommendations from the county’s Fair Election Fund Work Group, which was chaired by Jones and included community members, elected officials and community members.

Councilmembers A. Wade Kach (R) Thomas E. Quirk (D) introduced an amendment to limit expenditures by candidates who participate in the program to $1.4 million for county executive and $150,000 for county council candidates. The council approved that amendment, with only Councilmember Todd K. Crandell (R) voting against it.

Council members also raised the threshold that candidates would have to meet to show a viable campaign and qualify for public financing. As introduced, the threshold was 125 donors and $10,000 for council candidates, and 500 donors and $40,000 for county executive candidates. Those thresholds were raised to 150 donors and $15,000 for council candidates and 550 donors and $50,000 for county executive candidates.

Kach and Quirk previously expressed concern that the public campaign financing program would further drive up election costs in the county. But fair elections advocates have said expenditure caps like the one amended to the bill on Monday will make it difficult for participating candidates to compete against opponents who accept donations from corporate donors and special interest groups.

“The original qualifying thresholds recommended by the Work Group were in line with other jurisdictions and, for the first time candidate, were already difficult to reach,” Common Cause Maryland Executive Director Joanne Antoine said in a Tuesday statement. “The unnecessary spending cap also leaves participating candidates at a disadvantage when up against a well-funded challenger. It also counters the program’s goals of engaging more donors. It’s disappointing and I challenge every member of the Council who supported this change to adhere to these same spending limits during the next campaign. Let’s truly level the playing field so candidates from diverse backgrounds can run competitive races.”

Emily Scarr, the director of Maryland PIRG and a member of the workgroup, said in an interview last week a spending cap would only work if every candidate had to participate in the program — and local governments aren’t allowed to require candidates to opt into public campaign financing programs.

In a Tuesday statement, Scarr said the new program will “expand opportunities to run for office, lower average contributions and increase participation in local government” when it rolls out in 2026, but added that the spending cap “could undermine the ability of candidates to run truly grassroots campaigns, and encourage traditionally funded candidates to dramatically outspend them.”

Olszewski, who made public campaign finance a key campaign promise during his 2018 county executive bid, celebrated the measure’s passage in a statement — but said he was “disappointed” by the last-minute addition of spending caps.

“This is an important step for the future of democracy in Baltimore County. A Fair Election Fund will help empower diverse candidates, limit the influence of special interests, and strengthen our local elections,” Olszewski said in a written statement. “I called for this throughout my campaign for County Executive, made it my first legislative priority after taking office, and Baltimore County voters overwhelmingly approved it last year. While we’re disappointed unnecessary limits have been added to this program, establishing this Fair Election Fund is an historic step forward in ensuring the volume of one’s voice does not depend on the size of their wallet.”

In addition to Maryland’s statewide public financing system, various local jurisdictions have similar programs. Montgomery County was the first to set up a program in 2014, and Baltimore City, Howard County and Prince George’s County have all since enacted their own programs. Baltimore County’s public financing system will be the only in the state to include expenditure limits.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to include comments from Baltimore County Executive John A. Olszewski Jr.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution