Greed could kill Maryland’s citizen legislature.

The low grumbles you hear in the background are the voices of legislators who believe that pay raises will deter or convert those among them with larceny in their hearts and bribery on their minds.

High demand and low pay are advanced as explanations, if not excuses, for recent indictments of several vendible lawmakers and other officials.

Opening day is a window on legislators’ thoughts for the next 90 days. There are nearly enough TV cameras as there are lawmakers eager to be interviewed in the grand lobby separating the House and Senate chambers.

On that recent occasion, several, responding to pointed questions, offered that higher salaries for what they view has become a full-time job, might discourage the venality and sticky fingers that have made news lately – not that the offenses are anything new in the State House.

Sorry, folks, but that explanation (it surely isn’t the answer) is insufficient. Now, right up front, nobody’s denying diligent legislators a few extra bucks, but the law and history tell a different story. And, admittedly, times change and a couple of centuries make a huge difference in demands on time and talent.

The Maryland General Assembly, as conceived and designed, was never intended to be a full-time job. Nor was it fashioned to be a career opportunity for professional lawmakers. Legislating is, in a sense, volunteer work. It’s not like employment at a law firm or a brokerage house.

Many, if not most lawmakers have outside jobs in addition to their elected positions as legislators. Membership in the Assembly was not ordained as public service for private gain.

The Assembly, as an institution, was always, then as now, simply a coming together of citizens to conduct the public business of their jurisdiction(s).

Frank A. DeFilippo

The Maryland Legislator’s Handbook, published by the Department of Legislative Services, is clear on the point: “The Maryland General Assembly has remained a part-time ‘citizen legislature’ for more than 350 years. It is an evolving entity that began with a membership composed of farmers, tradesmen, and attorneys. While there are still farmers, small business owners, and attorneys who serve as members, educators, accountants, health care providers, public administrators, real estate agents and law enforcement officers now or have served in the General Assembly. Homemakers, retired persons, and members who consider themselves full-time legislators also serve in the legislature.”

What’s more, the legislature is prohibited from setting its own salaries. That is done by the General Assembly Compensation Commission, and it is usually carried out in an election year to set the salary schedule of the newly-elected incoming legislature so as not to violate the prohibition.

The annual salary of a legislator in Maryland has increased in steps over the past four years to its current level of $50,330 in addition to in-session per diem allowances and travel expenses, for annual 90-day sessions. The Senate president and House speaker are each paid $65,371.

To support their complaint about salaries, lawmakers note that their jobs expanded from part-time to full-time when the Assembly adopted the standing committee system and with the necessary attention to constituent services and community meetings to prop up their political continuity.

A ‘hybrid’ legislature

The National Conference of State Legislatures begs to differ. It breaks down state legislatures into three categories – full-time, hybrid and part-time. Sorry, Maryland General Assembly, but your own conference pegs you in the “hybrid” category, meaning that you’re lumped with 26 other states that are neither here, nor there, but a blur between full and part-time. And the average salary for hybrid states is $41,000, so you’re a good chunk of money above the average.

Examples of the 10 states that are listed by the NCSL as full-time legislatures include New York, Pennsylvania, California and Massachusetts, among others, where the average salary is $82,000. There are also 14 states that have what are regarded as part-time legislatures where salaries average $18,449.

More money, it also has been argued, will attract better qualified candidates to run for public office. That may, or may not always be the case. The ballot has always attracted gonzo personalities and manic adventurers, the silly along with the serious, into elections just for the hell of it. Consider the list of candidates for the Seventh District congressional seat.

Will a salary increase discourage funny money from the system of doing business in Annapolis? Or overcome the great temptations in that temple of moneychangers? That’s doubtful, too. That is, unless the bribers are eliminated along with the bribees.

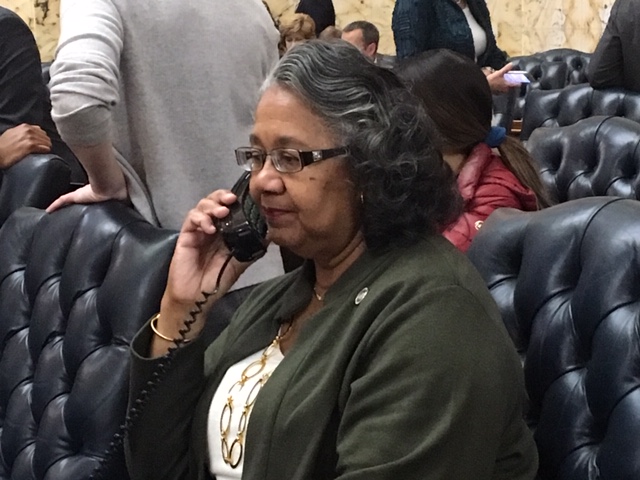

The two most recent inductees into the federal penal system were hardly doing God’s work for serious money when they got caught with their fingers in the collection plate. Del. Cheryl Glenn, of Baltimore, passed off her property tax bill as the cost of doing business with her to an anonymous figure whose identity might soon be revealed. And Del. Tawanna P. Gaines, of Prince George’s County, used campaign funds for cosmetic improvement and dental work. Gaines took her daughter and campaign treasurer, Anitra Edmond, down with her.

There were other scandals in Prince George’s, too, involving legislators and liquor laws, County Executive Jack B. Johnson and cash stuffed into his wife’s brassiere, and the late Sen. Ulysses Currie, who beat bribery charges for not reporting large amounts of money he received for consulting work.

But Maryland’s First Lady of illicit money is former Baltimore mayor Catherine Pugh, who parlayed borderline-literate kids’ health books into a million-dollar ponzi scheme — the fudged sale of books that were never delivered to people and groups, often the same book orders to different people, that she regulated as mayor and state senator.

Such mundane reasons for bribery and extortion are hardly signs of distress and desperation or an excuse for taxpayers to pony up additional funds. But they are more of a spiritual indication of venality and weakness of character, more likely just plain stupidity.

Lean to the latter for likely an accurate characterization. Often, too, the perps are convinced they’re so clever they’ll never get caught.

Shakedown accomplished

Back in the bad old days, circa the 1960s, legislators’ salaries were $1,500 per annum. At the time, there were alternate 90-day, 30-day sessions. In the years of the 30-day sessions, only the budget and statewide bills could be considered. No local legislation was allowed.

Back then, there were no standing committees to conduct business year-around. That was done by a joint body of senators and delegates called the Legislative Council that met monthly. And here’s the kicker: The Council’s members were paid a per diem fee per meeting. They convened and adjourned as many as a half dozen times at a single sitting, and considered each issue a separate and new meeting. They paid themselves the daily fee for each separate meeting, and collected a half dozen or more fees for a single day’s work. They got caught.

Here’s another example of the legislature at work during the same period: Every year, a certain delegate from Baltimore City (who, to avoid speaking ill of the dead shall remain nameless) introduced the same bill that would have established financial penalties against the same prominent company – called a “bell-ringer” in legislative parlance. At a certain point in the session the bill was always quietly withdrawn, and the delegate and his wife could be seen thereafter having dinner at the more expensive restaurants in the Capital City. Shakedown accomplished.

The General Assembly structure and system was reformed in the mid-1960s into its present standing committee system and annual 90-day sessions under the direction of the Eagleton Institute at Rutgers University.

Reform comes to the legislature

Lawmakers’ salaries caught up with the reforms in 1970, when the voters approved a Constitutional Amendment creating the General Assembly Compensation Commission. This, in effect, removed the tetchy problem of increasing salaries from the legislature itself and transferred the assignment to an appointed commission, as it exists today.

In the 1960s, the governor’s salary was $15,000 a year, plus, of course, the go-withs – room-and-board at the mansion, yacht, cars, etc. When Spiro T. Agnew became governor in 1967, the salary was increased to $25,000, the same number that applied to Marvin Mandel when he succeeded Agnew in 1969.

In 1974, a Constitutional Amendment to raise the governor’s salary to $45,000 was rejected by the voters at the same time Mandel won reelection with 65 percent of the vote.

There was an ironic twist to those numbers. The defeat of the salary increase was interpreted internally, and later supported by polling, as voter disapproval of Mandel’s very public dumping of his wife for a 38-year-old divorcee but at the same time affirmation of his job performance as governor.

The Governor’s Salary Compensation Commission was established by Constitutional Amendment in 1976, again removing the delicate subject of salaries from the governor and the legislature.

That commission functions to this day, and the Maryland governor’s current salary of $180,000 is among the 10 highest in the nation, just below, for example, those of the governors of California, New York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. The highest is California, the most populous state, at $201,680.

In a state as wealthy and as generous as Maryland, the numbers say that nobody in public office is underpaid. The actions of the malefactors belie that their wants may exceed their needs. And that’s not likely to change, even with higher salaries.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution