‘Self-Destruction’ biography offers richly detailed, layered history of late Sen. Daniel B. Brewster

“Self-Destruction: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of U.S. Senator Daniel B. Brewster.” By John W. Frece, Apprentice House Press, Loyola University Maryland, 2023. Illustrated with 25 pp. of photographs. 362 pp. Hardcover, $37.99.

***

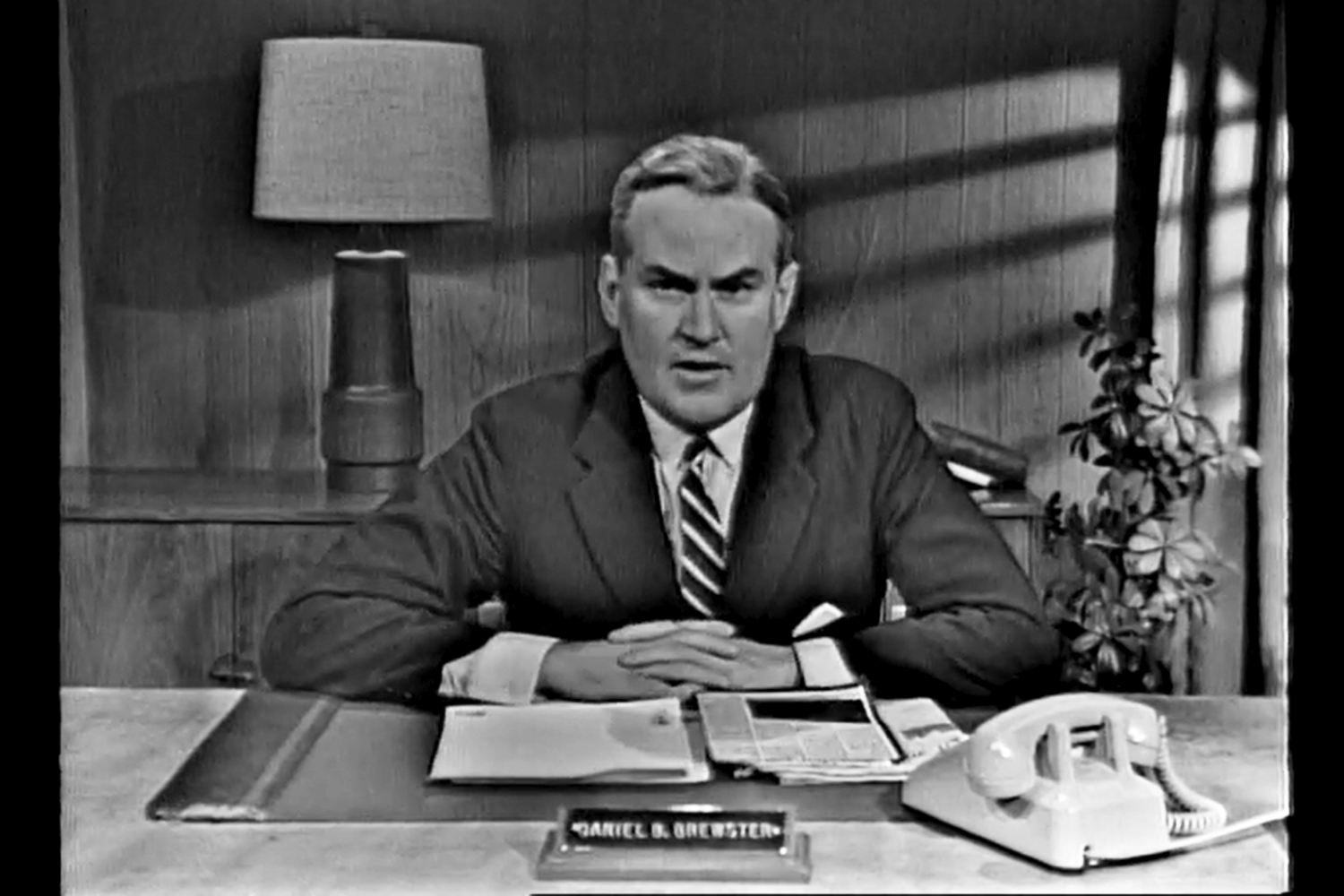

The prologue to a new biography of Daniel Baugh Brewster opens with an unforgettable scene that foreshadows the brutal descent of the former U.S. senator in the pages that follow.

Awakened in the middle of the night at his Baltimore County estate by a barking dog, Brewster is roaring drunk, standing at his bedroom door, waving a loaded Colt .45, the same sidearm he had carried nearly 30 years earlier as a young Marine lieutenant in World War II’s ferocious fighting of the Pacific, where he was wounded seven times. He is in his skivvies — boxers and a T-shirt — demanding that his teenage son Gerry “go shoot that damned dog,” as the boy’s sleepover buddy looks on in horror.

That picture is a difficult image to wipe from a reader’s mind. It is not a particularly endearing picture of our hero, who had held such promise as a rising national political star, only to crash back to earth as the demons of a fatal flaw overwhelmed him.

With that, John W. Frece, a former Maryland State House bureau chief for The Baltimore Sun, begins “Self-Destruction: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of U.S. Senator Daniel B. Brewster,” his fourth book and first solo biography.

It is a curious, and in some ways courageous, choice for Frece to start the book with such an unflattering snapshot.

While Brewster had fallen low at that point, he had not yet hit rock bottom; that was still another two years off. But with that opening, Frece captures alcohol’s deep personal cost to Brewster and those around him, and offers a hint at just how long a climb to any sort of redemption the former senator faced. Whether it was genetics or post-traumatic stress syndrome from battle at the root, it was the drink that was the prime driving force behind Brewster’s undoing.

Frece’s book reflects a reporter’s curiosity and eye for detail, bolstered by scores of interviews, deep research of Brewster’s papers at the University of Maryland’s Hornbake Library, access to the former senator’s war diaries, newspaper clippings and a generous assist from the family and their own papers. Of particular help was son Gerry L. Brewster, a one-time member of the Maryland House of Delegates, who wrote his senior thesis at Princeton University on his father’s journey up and down, and has championed the elder’s story over the years.

Despite inimitable help from the Brewster family, Frece writes an unvarnished tale, as the reader continues along with a one-eyed wince in anticipation of the former senator’s next drunken stumble and embarrassment. In the end, Brewster succeeded in finding sobriety after two unsuccessful attempts, had three marriages, two of which ended in divorce, and endured a corruption scandal that dragged on for years in federal court after he left office.

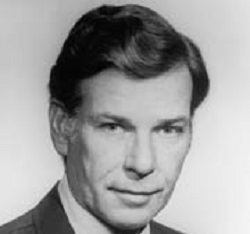

In the beginning, though, Danny Brewster was a dream candidate — a war hero, remarkably handsome, a young lawyer and family man, born to the landed gentry in wealthy Worthington Valley, a so-called “gentleman jockey” who rode across northern Baltimore County’s fields in fox hunts and point-to-point steeplechase races.

For a time he was known as the “Golden Boy of Maryland Politics” — a title Frece references — among the first of his generation to seek public office after serving in the war.

First elected in 1950, Brewster (D) spent two terms in the Maryland House of Delegates, before training his sights on a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing the Maryland’s 2nd District, where he served another two terms. In 1962, he lined up with a host of others to run for an open U.S. Senate seat, which he won.

President John F. Kennedy (right, in rocking chair) accepts an invitation to participate in the dedication ceremonies of the Delaware-Maryland Turnpike on November 14, 1963. Seated on sofa (left to right) are Sen. Daniel B. Brewster (D-Md.), Maryland Gov. J. Millard Tawes (D), and Delaware Gov. Elbert N. Carvel (D). White House photograph via John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

He was just 39 when he was sworn in as the junior U.S. senator from Maryland, rubbing elbows with the young President John F. Kennedy and standing on the ground floor of the New Frontier, an up-close witness to and participant in a decade of tremendous change and tumult.

Frece’s description of the 18 years Brewster spent in elected office is rich and insightful of the times, chockful of local and national political characters, whose names are still known today.

He benefited from interviews with the subjects of two autobiographies he co-wrote with former Gov. Harry R. Hughes (D) and former U.S. Sen. Joseph D. Tydings (D), both of whom had long been friends of Brewster.

He was also lucky enough to interview former staffers of the senator, including two who grew to hold powerful positions in the U.S. House of Representatives — Rep. Steny H. Hoyer (D-5th), former president of the Maryland Senate and former U.S. House majority leader, and Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), twice U.S. House Speaker, daughter of a former Baltimore mayor and sister of another, who also wrote a forward to Frece’s book.

Brewster’s time in Camelot was short-lived. Within months of his being elected, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, and Lyndon B. Johnson, one-time master of the Senate, ascended to the presidency, as the nation again struggled to find its footing.

Frece weaves a fascinating tale of one of the more compelling political dramas in Brewster’s life — when he ran for president in Maryland’s 1964 Democratic primary as a “favorite son” surrogate for LBJ against Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace (D), the notorious segregationist.

The race took place against the backdrop of the U.S. Civil Rights Act, stalled in the Senate because of a rock-solid filibuster by the Southern Democratic bloc. Brewster, a fierce advocate of civil rights, was the only senator from a state south of the Mason-Dixon Line to co-sponsor the legislation.

Throughout what became an ugly race against Wallace, he was regularly harangued at campaign stops and fielded thousands of racist letters disparaging his stand on civil rights. He was booed, shouted at and spat upon, and his wife was threatened, prompting the police to guard their home on the Baltimore County farm.

In the end, he beat Wallace by more than 10 points, but he was stunned that the Alabama governor had managed to receive 43.5 percent of state’s vote, compared to his own 54 percent. He barely carried his home turf of Baltimore County, where he won by just 324 votes, Frece points out. Maryland was still a very Southern state.

The presidential bid as LBJ’s surrogate against Wallace, however, seemed to rattle his confidence and take a toll, Frece writes. Afterwards, friends and colleagues began to notice Brewster’s drinking increase markedly, where at one point he was even seen guzzling Listerine mouthwash for its alcohol content.

Yet, he still managed to function. Among his most noteworthy accomplishments, Brewster was responsible for preserving Maryland’s portion of Assateague Island as a national seashore park, rather than allowing it to become the oceanfront development it was on its way to being.

Toward the end of Brewster’s six years in the Senate, his behavior became more erratic. He showed up hours late for speaking engagements or too drunk to address the crowd or sometimes not at all. He began to flip-flop noticeably on issues. His first marriage crumbled and he quickly married an old flame in a rather public display. The more he tried to control his drinking the worse it seemed to get.

Then came the allegations of improprieties with his campaign contributions, which had been left up to a dubiously trustworthy staffer, a matter that ultimately would return to haunt him.

Finally, he lost his 1968 re-election bid, in which he faced his very good friend, Charles M. “Mac” Mathias (R), a liberal 6th District congressman from Frederick. Mathias’s entry in the race shocked him — and then knocked him out of the box.

The Senate loss only seemed to hasten Brewster’s downward spiral, which included the demise of his second marriage and his hospitalization for alcoholism.

Then, just over a year later, in December 1969, he was indicted on federal bribery charges over payments made to him by the Spiegel Inc. mail order firm related to his votes on postal rate legislation while sitting on the Senate’s Post Office and Civil Service Committee, a case that would later reveal the involvement of a once-trusted aide.

The case against him went up and down the appellate ladder twice and was once before a jury, which found him not guilty of the bribery and corruption charges. Before it all was over six years later, a weary and broken Brewster pleaded nolo contendere to a single misdemeanor charge of “accepting an unlawful gratuity without corrupt intent” and was fined $10,000. The no-contest plea meant he did not admit guilt, but acknowledged the conviction and punishment. He maintained his innocence to the end.

Danny Brewster finally got sober, met his third wife in rehab and had three children with her. He repaired to his Baltimore County farm, where he worked the land and eventually wound up buying and racing thoroughbred horses. By every account, Frece writes, he seemed happy.

He kept his hand in public service, but only peripherally, agreeing occasionally to chair various state commissions and boards of private institutions.

Brewster died of cancer Aug. 19, 2007 at his home. He was 83.

Frece’s well-researched and documented biography of Danny Brewster is a worthy bookshelf addition for any student of Maryland political history. In the interest of full disclosure, I worked closely with John Frece for most of the 11 years he was at The Sun and have known him longer, but I don’t believe that changes the value of this book in understanding the politics of the last half of the 20th century and how Maryland evolved into what it is today.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution