By Shay Taylor

The writer is a citizen of the world, a resident of Baltimore City and a lifelong voter.

Think disenfranchisement isn’t your problem? We live in Maryland, after all. You’re registered, a citizen, not trying to break any laws. You have voted your entire adult life. You’ve contributed. It could never happen to you, right? Think again!

A North Carolinian by birth, my widowed, retired, cancer-survivor mother moved to be near me, her only daughter, and one of the first things she did as a Marylander in 2002 was register to vote. She had never missed an election.

As a girl, Evelyn Waugh worked in western North Carolina tobacco fields and competed in 4-H dress reviews and speaking competitions to save enough money to put herself through college. At 19, she married Sam Taylor, a local boy and son of a tobacco farmer. With a major in home economics and a minor in science, Evelyn became a Home Ec teacher in Surry County and lived with her in-laws while my father was in Japan for 18 months, as part of the U.S. occupation following the Korean War. And in every election since she turned 21, she voted.

Fast forward past getting her children to school age, to her five years as a 9th grade science teacher in a rural high school in Catawba County, North Carolina. She impacted students there who, upon meeting her again years later said, “Mrs. Taylor! You’re the reason I became a doctor or a nurse or a fill-in-the-blank!” These have been among this born educator’s proudest moments.

At her core is a belief in America’s children and the future they represent. Leaders in the central office also saw her talents, plucked her from the classroom, and encouraged her to earn her master’s degree to influence more students by supporting their teachers as High School Supervisor and then Director of Instruction — the cap to her 30-year career. During these years, she was also an active member of the League of Women Voters — always understanding the importance of voting rights. And every election, she voted.

She retired and my father died in quick succession in June 1994. Soon after, Appalachian State University called. They didn’t have enough qualified supervisors for student teachers. Evelyn Taylor knew the Catawba County high schools better than anyone and they needed her. She’d help out for one semester, she told them, but she was retired. She loved working with the student teachers and ended up working for another decade, only stopping at age 70 after a bout with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

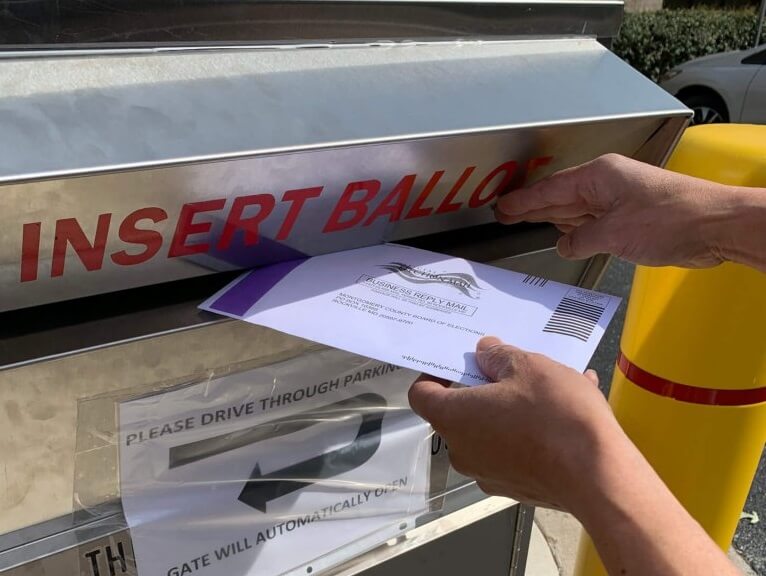

My mother lived with me in Baltimore County for seven years, until my travel for work and her frequent falls became too great a concern. We found an independent living apartment for her 13 years ago. We no longer had the same polling place, she no longer drove, and even walking caused her severe pain, but she was relieved that the Baltimore County Board of Elections would mail her an absentee ballot for every election. With her failing eyesight, we’d take time to read the ballot together and for her to tell me whose background, experience, or gumption was earning her vote. She always voted — until this year.

Mom was quite ill during May and June and into July. I called the Board of Elections and learned that this year she had to request and return a form in order to receive her ballot. Since she was in the hospital, and we weren’t sure where she would be when the ballot arrived, she requested it be sent to my Baltimore City apartment. That was about a month before the election. While she was in rehab for physical therapy, we celebrated her 70th wedding anniversary, and every day I checked my mailbox for her ballot.

I called the Board of Elections again more than a week before Election Day, only to be told that “it’s in the mail” and there was nothing we could do if the ballot didn’t arrive. Nothing to do. No way, after avoiding COVID, after never missing an election, after rallying from this latest illness, nothing to do to cast her vote in this Maryland primary election.

At 7:30 p.m. the night before the July 19 primary, her ballot still had not arrived. I work. I’m trying to care for her, and I wanted to make it possible for her to vote. The next morning, after I voted in Baltimore City, I checked my mailbox again. There it lay — with a cover letter dated July 15, apologizing for the lateness, but saying they “needed to verify your address or check that you were in the correct district after the recent redistricting process.” They went on to tell her to return it by mail. “It must be postmarked on or before July 19. Return it in a ballot box by 8 p.m. on July 19. Return it to [her] local board office.” I made it to my mom, ballot in hand, at 6 p.m. on July 19. “I’m just too tired,” she said.

This is the first time my 89-year-old mother has missed an election. I would like to remind the powers that be that mail-in ballots are not only for those who want the convenience of this voting option. For the disabled, the elderly, and those with transportation difficulties, it is a vital voting option. Maryland’s legislators and courts know that the cries of voter fraud are a diversion from the facts, but they have disenfranchised a life-long, politically intelligent voter, in what may be one of the final opportunities of her life to participate in the political process — a duty she holds sacred and which she instilled in her children and grandchildren.

In September, she will move back to North Carolina to live with my brother. Perhaps her voting rights will be safer there. Who’d have thought?

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution