Net Zero Energy Schools Raise Bar on Green Construction Statewide

On his first tour of Wilde Lake Middle School in Columbia, Christopher Rattay watched a fleet of solar cars whiz up and down the sixth-grade hallway. He would learn from the enthusiastic young operators that they were built for a class project. The new principal knew right away that Maryland’s first net zero energy school would be a wild ride, that the $34-million facility, which opened in 2017, had the potential to be something special, both as a learning laboratory and a model for school construction.

“The [building] itself is gorgeous and contributes to good health and a sense of emotional well-being,” said Rattay, who was struck by the “open spaces and natural light” in the halls, stairwells and classrooms.

“Net zero energy [means] any electricity we use is electricity that we produce, whether it’s our solar panels on the roof, or those on the grounds,” said school resource teacher Doug Spicher. He said the construction plan also called for 112 geothermal wells to heat and cool the building, a large array of light and water sensors and other conservation measures. Sunshades and coatings on the windows decrease the amount of sunlight that penetrates the building so school rooms don’t get sweltering hot or cold, Spicher said.

The new school, completed in 2017, is nearly 50% larger and uses 50% less energy than the building it replaced.

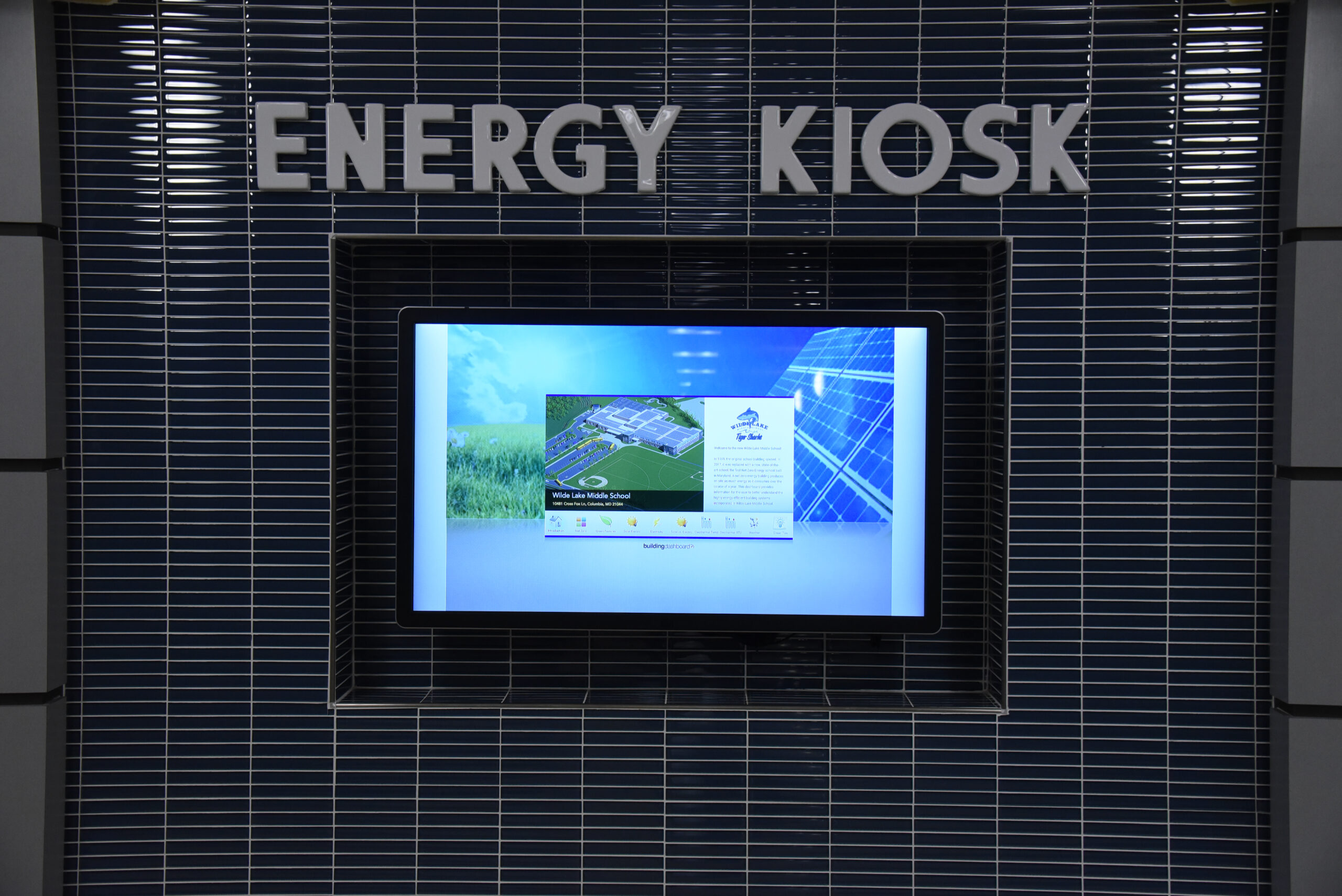

Wilde Lake can also serve 760 students, up from 500 at the previous building. Mariam Abimbola said she was “privileged” to be one of them. Now a junior, she said she made frequent stops at the energy kiosk in the front hall that streamed environmental data in real time. “[The display] made you look at the electricity we were using, the electricity we were saving,” she said. “Before that we weren’t really conscious of our energy use, that we could really do better, and change our ways, at school and at home.”

Wilde Lake Middle School’s solar array includes 1,400 roof-top and another 600 on the ground. Screenshot from Howard County Public Schools.

Dan Lubeley, director of capital planning and construction for the Howard County Public School System, follows that data closely, and is pleased with the results. “The building is actually performing better than expected,” he said. “It is one less facility to potentially consider within the operating budget because it is producing enough energy. So, it’s not an added cost.”

Schools are built to last 20 to 25 years without major renovation.

Lubeley said Wilde Lake provides valuable lessons. “School construction has always revolved around the basic concept that it has to be sustainable, durable, and maintainable,” he said. “So [in future projects] even if we are not going to do any solar, that doesn’t mean that we wouldn’t take into consideration the efficiency of our wall construction, or other green design features.”

Green construction, a state priority

In an average year, Maryland’s 24 school districts perform renovation or major maintenance on more than 200 of the state’s 1,400 public pre-K-12 school buildings, according to Alex Donahue, deputy director for field operations for the Maryland Interagency Commission on School Construction, which directs state construction funds to each local school district.

“To give you a sense of the magnitude of that effort, the state has averaged about $400 million a year for school construction projects,” said Donahue. That figure was increased by the Built to Learn Act in 2021 by an additional $2.2 billion over five years. “So, it’s almost doubling, about $800 million per year going out to school districts to invest in school facilities.”

School districts are advised, but not mandated, how to use those funds.

“Green construction is a state priority,” Donahue said. “State law requires that every new school facility and full renovation be a high-performance building and meet stringent state and international building codes. I don’t think many states have adopted tougher measures.”

While no new net zero energy schools are currently underway, Graceland Park/O’Donnell Heights Elementary/Middle School and Holabird Academy in Baltimore became the second and third such schools in Maryland in 2020.

The two buildings, located near each other, shared design plans and architects, and leveraged a $5 million grant from the Maryland Energy Administration. “Significantly, Baltimore City found they were able to build those very green net zero energy schools for a negligible cost premium above the average or standard cost for a non-zero energy building, which really tells us that net zero energy is not just achievable but affordable,” Donahue said.

More net zero schools ahead?

Early in this year’s legislative session, Sen. Paul G. Pinsky (D-Prince George’s), chair of the Senate’s Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee, introduced the Climate Solutions Now Act of 2022. Sponsored by a majority of Maryland senators, the bill calls for a 60% reduction in greenhouse emissions from 2006 levels by 2030, and net zero carbon emissions by 2045.

A geothermal heating and cooling system regulates the temperature at Wilde Lake Middle School, Maryland’s first net zero energy school. Screenshot from Howard County Public Schools.

“I think utilizing public facilities, public policy as it affects the government … is a good way to get started on changing people’s practices,” Pinsky said in an interview.

Pinsky said schools can play an important role, given that buildings and construction generate nearly 39% of global carbon dioxide emissions, according to a report from the World Green Building Council.

The climate bill would also require at least one school constructed in each local school district to be net zero by 2033. It also establishes a Net-Zero School Grant Fund, which would give school districts up to $3 million to cover the difference in costs for a net zero building.

“It will actually make money for school systems because they will be saving money normally spent on energy costs. But we need some kind of incentive,” Pinsky said.

Lubeley, the Howard County schools construction director, said Wilde Lake is a gem within the county and a beacon for change for Maryland.

“It showed [us] that … this is a potential direction that the state or the school system could go,” he said.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to correct the spelling of Alex Donahue’s name.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution