Lawmakers Again Take Up Special Elections For General Assembly, Other Election Reforms

A perennial push to bring special elections to the Maryland General Assembly is back again in 2022.

Senate Bill 73, sponsored by Sen. Clarence K. Lam (D-Howard County) is the latest attempt to fill legislative vacancies by election. Vacancies are currently filled by gubernatorial appointments based on party central committee nominations.

Lam’s bill would require that, if there is a vacancy in the state Senate or House of Delegates at least 55 days before the candidate filing deadline for regular statewide elections held in the second year of a lawmaker’s four-year term, the governor would need to declare special primary and general elections to decide who will fill the vacancy.

Lam said special elections would limit the influence of political insiders on the General Assembly.

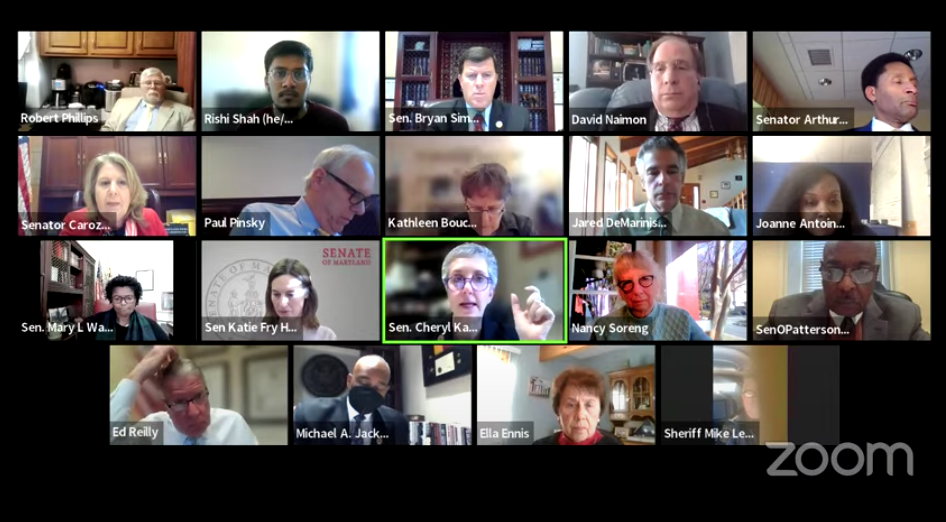

“There are some jurisdictions where this process means that only a handful of well-connected individuals can determine the representation of thousands of voters,” Lam told members of the Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee at a virtual hearing Wednesday.

If the vacancy occurs after or fewer than 55 days before a filing deadline, the current appointment process would remain in place.

A sizable portion of the General Assembly — about a quarter of all lawmakers — was originally appointed rather than elected to the legislature. Five new delegates were appointed to the General Assembly since the end of the 2021 legislative session:

- Del. Linda Foley (D-Montgomery), the former head of the Montgomery County Democratic Central Committee, was appointed to replace Del. Kathleen M. Dumais, who was appointed as a Circuit Court judge.

- Del. Faye Martin Howell (D-Prince George’s), the former treasurer of the Prince George’s Democratic Central Committee was appointed to replace Del. Erek Barron, who was appointed by President Biden to become Maryland’s first Black U.S. Attorney.

- Del. Cheryl Landis (D-Prince George’s), the former chair of the Prince George’s Democratic Central Committee, was appointed to fill the seat of Ronald L. Watson (D-Prince George’s), who was appointed to the Senate.

- Del. Rachel Muñoz (R-Anne Arundel) was appointed to replace former Del. Michael E. Malone (R), who was appointed as a Circuit Court judge.

- And Del. Roxane Prettyman (D-Baltimore City), a member of the Baltimore City Democratic Central Committee, was appointed to replace former Del. Keith Haynes, who retired in July.

If the constitutional amendment was already enacted, for example, a special election for the current term would have been triggered for a vacancy before Nov. 30, 2019 — 55 days before the Jan 24, 2020 filing deadline for primary candidates.

Morgan Drayton, the policy and engagement manager for Common Cause Maryland, said the current system means that appointed lawmakers can serve almost an entire term without their constituents having a say.

“This is a straightforward bill that, while not a perfect solution, would definitely be a step towards a more democratic process,” Drayton said.

Ralph Watkins of the Maryland League of Women Voters described the bill as a “very prudent compromise” and said the costs of the special elections would be minimal, since the special election would occur at the same time as regularly scheduled presidential elections.

Committee Chair Paul G. Pinsky (D-Prince George’s) noted that the bill passed through the Senate in both 2020 and 2021, although it languished in the House Ways and Means Committee.

“We’ve heard this for two consecutive years and passed it over to the House,” Pinsky said. “Hopefully the third time’s the charm. “

The House committee has a new chair this year, Del. Vanessa E. Atterbeary (D-Howard). She was appointed to lead the committee in November, after Del. Anne R. Kaiser (D-Montgomery) stepped down from the post.

Recount reforms and more efforts to change election law

Senate Bill 101, an omnibus reform introduced by Vice Chair Cheryl C. Kagan (D-Montgomery County), would ban candidates for petitioning for a recount if they lose an election by more than 5% of total votes cast or if there is a 5% gap in the amount of votes cast for the prospective winning candidate and the losing candidate.

It also redefines when a candidate must pay for the cost of a recount as opposed to a county. Counties currently need to pay for the recount if the difference in the number of votes between the candidates is 0.1% or less. Kagan’s bill would change that to less than 0.25%. The bill would also add costs and assistance associated with recounts to candidates’ campaign finance disclosures.

“Super close, the county pays,” Kagan said. “Medium close, candidates can choose to play. Not close at all, there would not be a recount.”

Gubernatorial tickets that are participating in the state’s public campaign financing program or candidates participating in similar local programs would need to set up a “contested election committee” to receive donations and make disbursements related to contesting a “contested election,” defined by the bill as an election subject to a recount or judicial challenge. Kagan said that measure would serve to keep special interest money out of recounts involving publicly financed campaigns.

Pinsky said a similar bill passed the Senate last year, but the House of Delegates disagreed over what thresholds to use.

Senate Bill 158, another election reform from Kagan, would codify the longstanding election cost-sharing agreement between state and local boards of elections. The bill requires counties to pay half of the cost of election-related goods and services that are mandated by the State Board of Elections. Existing provisions, which aren’t enshrined in state law, require counties to pay half of the state’s voting system costs.

The Department of Legislative Services estimates the bill would save local governments $500,000 in the 2022 fiscal year and roughly $3 million annually after that — with those costs shifted to the state government.

Kagan said the bill would also require expenditures of more than $50,000 to be voted on by the State Board of Elections, and every expenditure be reported to them.

“If we’re talking about taxpayer money … we should have public awareness of that,” Kagan said.

She said counties would also receive itemized information about election costs.

The bill is one of the Maryland Association of Counties’ top priorities for the 2022 legislative session. Kevin Kinnally, the legislative director of the Maryland Association of Counties said the bill would provide “predictability” for county governments’ budgets.

“If the state mandates that local boards use particular systems or equipment, and if they’re going to oversee procurement of those systems or equipment, and the state chooses the vendor to supply those systems or equipment, then the state should have skin in the game and share 50% of the cost,” Kinnally said.

David Naimon, the secretary of the Montgomery County Board of Elections, said his board supported the bill’s provisions about codifying the cost split. Naimon, who was testifying on his own behalf, suggested amending the bill to ensure that the 50% threshold is the minimum the state can reimburse a county, but the state could choose to reimburse more.

“It should be clear that the counties wouldn’t be charged more than 50% of these costs,” Naimon said.

Senate Bill 112, also sponsored by Kagan, would make establishing fake ballot drop boxes a felony punishable by up to three years in prison and a fine up to $10,000 — a similar penalty to other already existing election-related offenses like damaging voting equipment.

Drayton said there was a “meteoric rise” in mail-in ballot and drop-off box use during the 2020 elections, and said the bill would deter interference with drop-off boxes. Kagan said fake drop-off boxes weren’t a problem in Maryland during the last election, but a few cropped up in other states.

Ella Ennis of the Maryland Federation of Republican raised concerns about “ballot harvesting,” or the mass collection and casting of ballots, and said the bill should prohibit the practice. Republicans in the General Assembly introduced amendments to election reforms on that topic during the 2021 legislative session, but Democratic lawmakers said the practice is already illegal under Maryland law.

Senate Bill 163, yet another election reform from Kagan reviewed by the Senate committee Wednesday, would allow election officials to begin processing mail-in ballots eight days before the start of early voting, although they wouldn’t be able to tabulate those ballots.

Kagan’s bill would also require election officials to provide precinct-level results. She said her bill also allows mail-in ballots to be cured, or fixed by voters, if they forgot to sign the oath on the ballot envelope. Kagan said she plans to introduce an amendment to the bill that would require local boards of elections to notify voters within three business days after election officials find that a voter didn’t sign the oath. The bill would allow voters to correct that error by text message, an accessible online portal, a mailed form, or an in-person visit to the local board office.

The bill would require that a ballot without a signed oath be rejected if a voter doesn’t fix it before 10 a.m.10 days after the election.

Rishi Shah with Maryland PIRG said more than 5,000 ballots in Maryland weren’t counted due to a lack of a signature on mail-in ballots in the 2020 election. He said allowing election officials to pre-process mail ballots before election day will allow them time to reach out to voters about fixing mistakes like a lack of signature on the ballot.

Senate Bill 63, introduced by Lam and Sen. Delores G. Kelley (D-Baltimore County), would add additional factors for election officials to consider when deciding whether a candidate or member of the General Assembly is a resident of their respective district. The state constitution stipulates that a person meets the residency requirement if they have lived in their district for at least six months before an election or, if the district is set up less than six months before the election, if they have lived in that district since it has been established.

The slew of additional factors in Kelley and Lam’s bill include: the address listed on a candidate or General Assembly member’s driver’s license or state-issued identification; the street address where they receive mail; whether their claimed address is zoned for residential use and complies with building codes; whether a candidate owns, rents or leases that property; whether there is proof they have paid for utilities at that property; if the candidate or General Assembly member’s children are registered for school at that address; whether their “spouse or other immediate family members” live at that address; whether an address is listed in records like tax returns; and whether the candidate is an active-duty member of the military.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution