Roz Hamlett: Can Past Be Prologue at Renewed Sparrows Point?

Maryland has embarked on a transformative course toward a world that runs on green energy. With the recent announcement that a prominent wind energy developer will expand its operations in southeastern Baltimore County, home of the iconic Bethlehem Steel Corp, the project has the potential to not only deliver on a clean energy economy, but also to correct a multitude of generational injustice.

At this critical inflection point for America, in the post-George Floyd era, lies the opportunity to create equity in wind energy jobs and to achieve a rebirth of the steel industry in Sparrows Point.

The federal government has established a goal of deploying 30 gigawatts of offshore wind in the U.S. by 2030, while protecting biodiversity. President Biden envisions that meeting this target will lead to the creation of tens of thousands of good-paying union jobs, and trigger billons in investments per year in projects like those off the coast of Ocean City.

Achieving this national goal is expected to create a cumulative demand of more than 7 million tons of steel – that’s equivalent to 4 years of output for a typical U.S. steel mill.

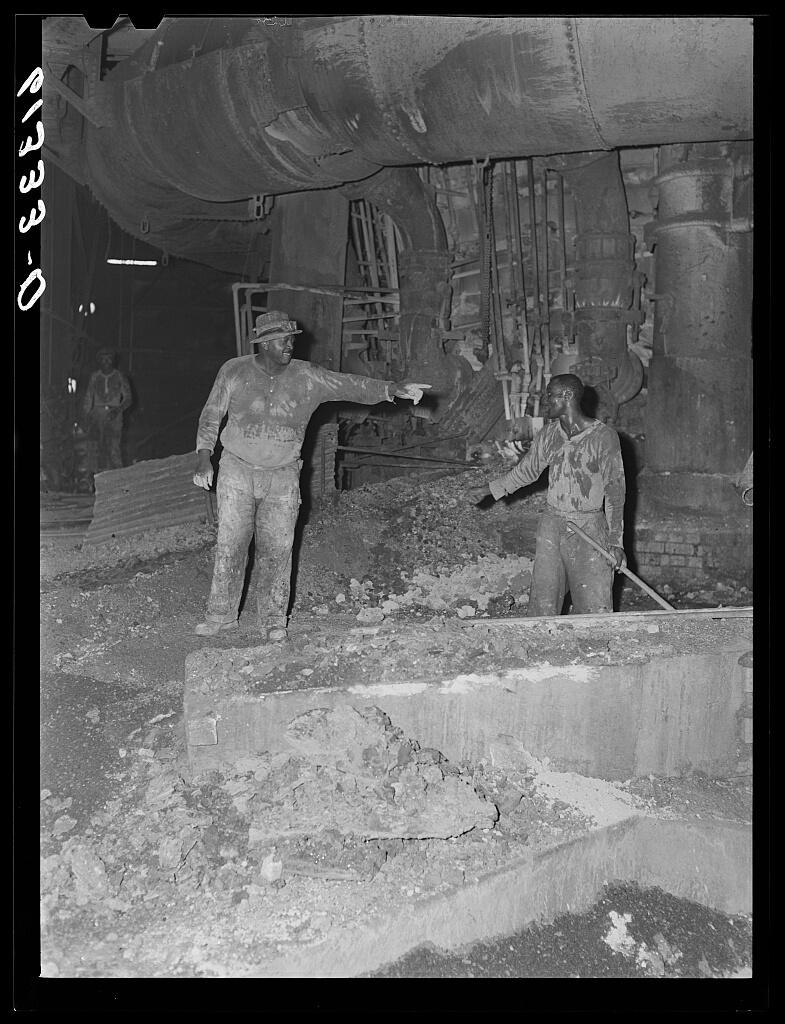

The repurposed Bethlehem Steel site reminds me of my family and the thousands of African American laborers, ironworkers, ship welders, and steelworkers employed there during the plant’s heyday who gained a firm foothold in the middle class. During the first 8 years of my childhood, we lived in Turner Station across Bear Creek from Sparrows Point. My father was a tractor operator and my uncle worked in the coke ovens.

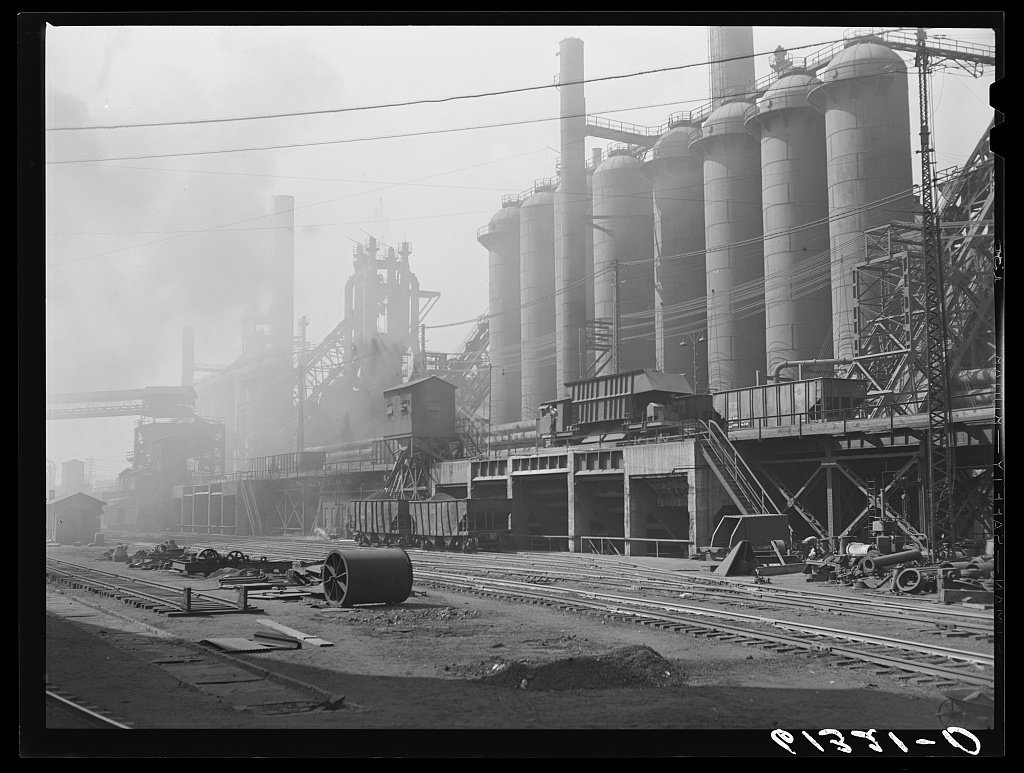

The Bethlehem Steel mill at Sparrows Point in 1940. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

I remember my uncle arriving home from work for Thanksgiving dinner once, exhausted, covered in red dust, and smelling of rust after his shift watching the red-hot slabs of steel bake in 2,000-degree ovens. The heat singed his skin even through protective clothing.

He fascinated us kids with exciting stories about running a jack hammer inside the hot furnace or his adventures beneath the mill into the flues of the open hearth where dirt spewed from smokestacks and collected on the floor. It was his gift to make a noxious and highly flammable environment of iron oxide the stuff of our dreams. But the reality of the coke ovens was harsh. It was the scene of fatal accidents, and the environment caused cancer, from which my beloved uncle died prematurely in his sixties.

A 2019 Johns Hopkins report by Andrew Cherlin describes Bethlehem Steel at its peak in 1957 when it employed some 30,000 people. White workers at the plant had mean family incomes of $6,665, which was above the national average of $6,262. The incomes of Black workers – while less than white steelworker families – were substantially higher than the majority of African Americans nationwide. In 1960, the mean income of Black households was about $3,800, but the mean income of Turner Station was $5,000. Compared to their white neighbors in Dundalk, they earned less, but relative to other Black families they earned more.

Residential segregation was stark, both in Dundalk and inside the plant. Dundalk was 99 percent white while Turner Station was about 91 percent Black. The plant itself was segregated too, with Black workers relegated to the hottest and most dangerous jobs. The bathrooms and locker rooms were segregated. The parking lot was segregated.

According to firsthand accounts from retired shipyard workers, in the wintertime, white workers were assigned to the sunny side of the ship and African Americans were put on the cold side. During summers, African Americans were on deck in the hot sun while their white counterparts were assigned below to cooler areas.

Despite such hardships, Turner Station was a prosperous community and Black steelworkers were a grateful bunch. They accepted social injustices and income disparities as the price to pay for unionized jobs that put food on the table, paid college tuition for their children and sustained the family. For instance, the health insurance benefits that paid for Henrietta Lacks’ cancer treatments at Johns Hopkins Hospital were earned by David Lacks, her Bethlehem steelworker husband.

In addition to Henrietta Lacks, whose cancer cells became the source of the immortal HeLa cell line and the workhorse of biological research, other notable residents of Turner Station include astronaut Robert Curbeam, NFL legend Calvin Hill, Congressman Kweisi Mfume, and Kevin Clash, the American puppeteer who performed and voiced Elmo on Sesame Street from 1984 to 2012.

Bethlehem Steel provided the means for my own family to move to an upscale neighborhood in Baltimore City of Black lawyers, judges, and doctors. The children and grandchildren of steelworkers in my extended family include an aeronautical engineer, an electrical engineer, an architect, a race car driver, a classically trained pianist, a commercial property manager, an international model, educators, a visual artist, and a couple writers.

The immigrant population in Dundalk once consisted of parents, grandparents and great-grandparents from Poland, Italy, Germany, and Ireland. According to the most recent Census, of the largely Hispanic foreign-born population in Dundalk between 2013 and 2017, 65 percent said they entered the U.S. in 2000 or later. Today the immigrant population in Dundalk are a diverse group of Mexicans, Salvadorans, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans.

The question remains as to whether the combination of wind energy and steel jobs can be the same economic bootstraps for a new generation of workers as Bethlehem Steel was once.

The possibility exists, and the story of Sparrows Point can serve as a critical road map to an entirely new local economy.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution