Frank DeFilippo: America Built Thousands of Miles of Roads to Nowhere to Move Edsels, DeSotos, Studebakers and Packards

Baltimore’s “Highway to Nowhere” may finally be going somewhere, and as far as neighborhood residents are concerned the roadway could be reimagined as the 10th circle of Dante’s hell.

Yet Baltimore is losing an important talking-point. Nearly every big city worth its name has at least one federally funded project that’s deader than a Pterodactyl and serves absolutely no purpose other than an archeological eyesore.

The western end of the freeway stub in Baltimore City intended for use by the canceled I-170, now dubbed the “highway to nowhere.” Photo by Adam Moss, Wikimedia Commons.

After more than 70 years of planning and dead-ending in the middle of the city, federal and local officials want to undo what their predecessors did in 1949.

In that fateful year, the ministers of influence at City Hall succumbed to the notion — and the influence of Detroit — that the future lay with the automobile and not public transportation.

They invited New York’s master planner, Robert Moses, to Baltimore to ascertain the city’s best means of getting its bulging post-World War II population from here to there in the most efficient manner. Back then, Baltimore was the nation’s 6th largest city with a population of nearly a million. Today it ranks 30th, its population diminished to 593,000.

Moses, never hesitant to apply bulldozers and asphalt where grass and houses bloom, hunched over a map of Baltimore and pondered the 92 square miles of urban lifescape.

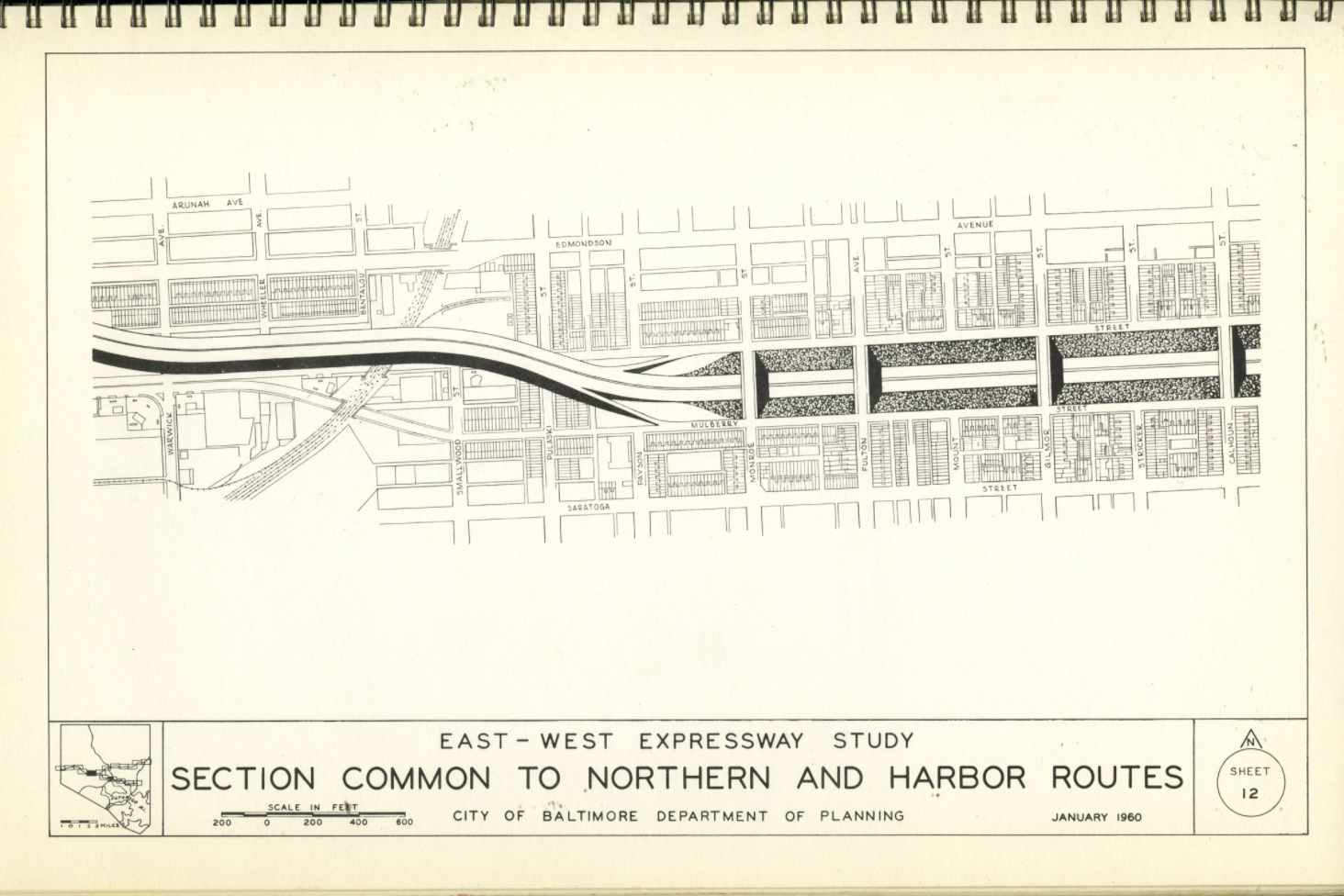

Moses scoffed to officials that the city’s configuration was misaligned: There should be an expressway extending from East to West, using his forefinger to draw an imaginary line horizontally across the center of the map, connecting Baltimore’s two outer margins.

And as witnesses to history repeating itself, the now defunct Red Line followed nearly the same East-West fingernail pathway across town through an unacceptable tunnel scooped though the city’s underbelly to Fells Point and Canton.

Some city officials and mass transit proponents hope to revive the Red Line project, though the set-aside funding has been applied elsewhere, mainly to roads in the outlying counties, while the deadline for federal funds expired.

Anyone who’s read Robert Caro’s masterwork, The Power Broker — among the best books on politics ever written — grasps Moses’ affection for highways, throughways, expressways, bypasses, freeways, and all the other asphalt sluiceways that dissect New York.

They include Jones Beach, accessible to the masses by highway and automobile, and the greenswards of Central Park, designed to be an oasis plop in the center of Manhattan, among the world’s foremost concentrations of skyscrapers.

Moses was seemingly unstoppable. He leveled huge swaths of New York, tore up communities, displaced hundreds of thousands of people, shut down businesses, reduced neighborhoods and buildings to rubble.

In doing so, Moses became a wealthy man. He created “authorities” to oversee each of his projects and collected a handsome salary as executive director of each of the oversight organizations he created.

Finally, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, encouraged by social critics and authors Jane Jacobs and Louis Mumford, put an end to Moses’ supremacy as New York’s “master builder” when he went one project too far — the proposed demolition of Greenwich Village’s landmark Washington Square.

Moses encouraged the same rapacious romp through Baltimore.

At about the same time Moses cast his asphalt spell over Baltimore, the city — like all deprived metropolitan centers — was emerging from World War II with pent-up consumer demands.

Rationing and limited wartime production of basic wants and needs fueled a wild spending binge on — those spiffy new automobiles that were rolling off the same Detroit assembly lines that had been converted to production of tanks and jeeps.

It had been accepted wisdom that Detroit itself was motivating the lust for cars by encouraging — and that’s a much softer word than was used to describe the auto industry’s skulking approach — city officials across the country to build highways instead of mass transit to usher in the new family mode of transportation. Los Angeles is a showcase example: LA is a great big freeway, as the song goes.

Thus, Baltimore, led by its profane and esteemed mayor, Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., began tearing up trolley tracks and replacing its cobblestone streets with asphalt for a smoother ride in those tail-finned, wrap-around windshield Packards, Chryslers, Ramblers, Oldsmobiles, Studebakers, DeSotos and Edsels.

Ironically, it was those flashy, chrome-crusted cars and their accommodating roads that would accelerate the flight to the suburbs and the gradual shrinking of the city’s population in the 1950s diaspora.

After years of planning and limited construction, it wasn’t until 1966-67 that the East-West Expressway was stopped in its path.

The high-decibel crusade of Barbara Mikulski, a born hell-raiser and social worker, brought down what Moses had wrought and along the way launched a political career that took her to the city council, the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate.

Mikulski fought the East-West Expressway as it would have caused upheaval and dislocation in her quaint Fells Point neighborhood just as it had on the Westside section of the roadway that was in the ground before the Inner-city highway was abandoned.

It was early in 1967, just a few days before Spiro T. Agnew would assume the governorship, that Jerome Wolfe, Agnew’s state highway commissioner-designee, confided that Agnew intended to kill the project.

Del. Keith Haynes (D-Baltimore City), U.S. Rep. Kwieisi Mfume (D), U.S. Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D), Baltimore City Mayor Brandon Scott (D), U.S. Rep. John Sarbanes (D), U.S. Sen. Ben Cardin (D), and U.S. Rep. Anthony Brown (D) held a press conference Monday in support of The Reconnecting Communities Act. Photo by Hannah Gaskill.

And now, as Maryland Matters colleague Hannah Gaskill has reported, Maryland’s Congressional delegation wants to repair the damage that was done to the West Baltimore community that was torn apart by Moses’ expressway to the future.

At an announcement ceremony at the site, they gathered with local officials to announce legislation that would reconnect communities that were dissected by federal infrastructure projects and abandoned long ago, especially in low-income areas.

They envision parks and other socially redeemable amenities to replace the 1 1/2 miles of concrete that go nowhere as a reproach and a reward for the disruption that the abandoned road caused.

There are numerous examples of reclamation projects in New York and across the country where abandoned railroad lines have been restored into green spaces and hiking trails and other environmentally friendly projects.

Most remarkable is New York City’s “High Line,” or “park in the sky,” an elevated rack of greenery in mid-town Manhattan conceived and built on abandoned railroad tracks where trains formerly delivered goods to the upper floors of warehouses among the city’s high-rises.

There are more than 4 million miles of navigable roadways across America, and the centerpiece of it all are the 47,432 miles of Interstate highways.

But probably the most romanticized roadway in the country is the “National Highway,” better known as the fabled “Route 66,” celebrated in the 1960s TV series of the same name, and in a popular song recorded by Nat King Cole — “(Get your kicks on) Route 66.”

It stretched for 2,451 miles, from Chicago to Los Angeles, and included as part of its linkage Baltimore’s old U.S. Route 40, still in existence but bypassed by I-95, leaving in its dust shuttered businesses and a desolate ramshackle road.

Route 40 is best remembered for the racial demonstrations of the 1960s when its businesses refused to serve black diplomats traveling between New York and Washington.

Established in 1926, and removed from the U.S. Highway System in 1985, Route 66 has been replaced by a network of five interstate highways. Today, Route 66 is a tourist attraction for nostalgia buffs and a sentimental journey for Corvette lovers who replicate the idealized trip of the TV show.

There are thousands of miles of deserted highways in America. President Joe Biden’s $4 trillion infrastructure package — now reduced to assuage Republicans — has lots of damaged and abandoned territory to recover.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution