Is Frosh Required To Represent Problem Cops? The Jury Is Out

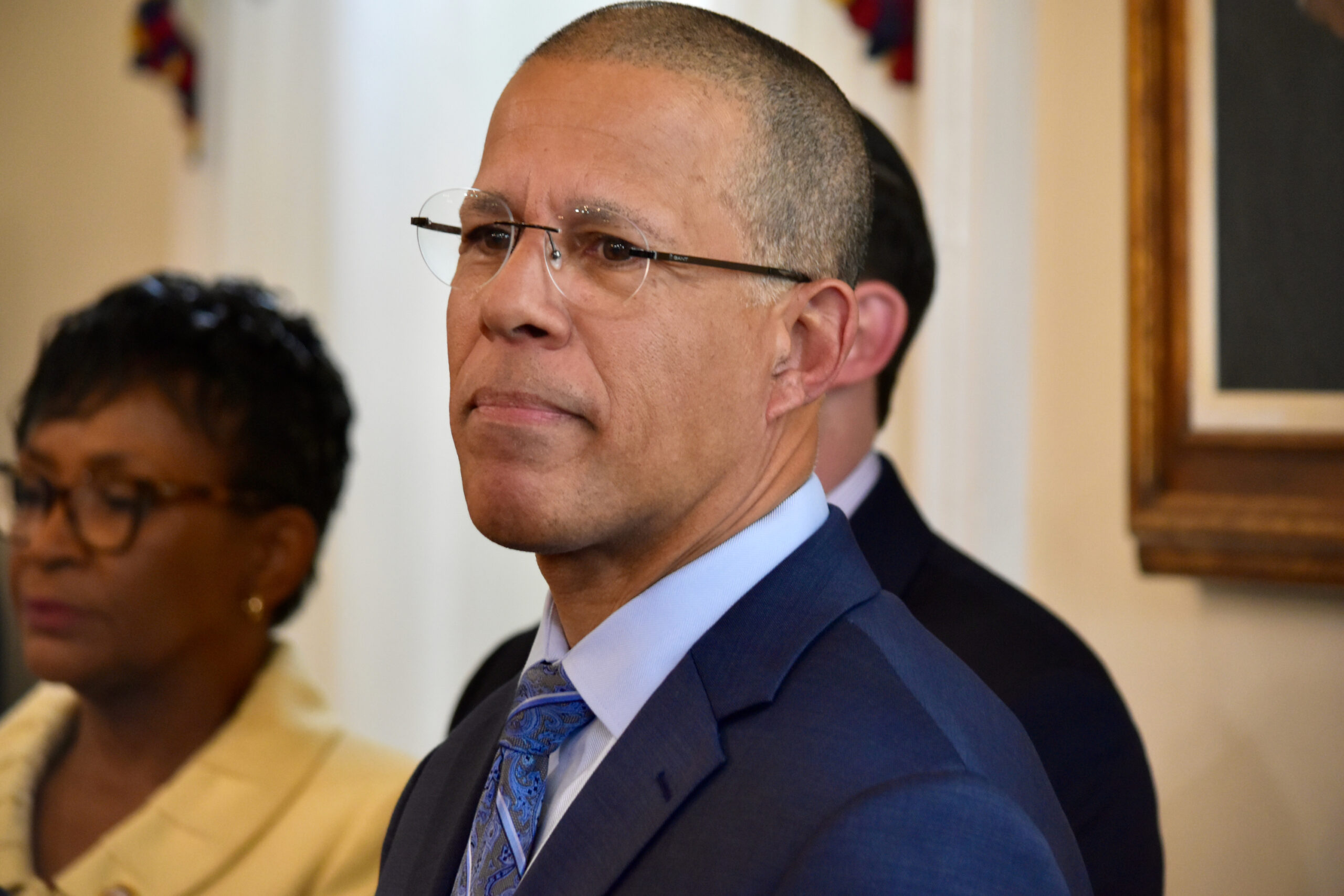

After former Maryland Chief Medical Examiner Dr. David Fowler testified in defense of the police officer convicted of murdering George Floyd, Attorney General Brian Frosh (D) announced he would review the autopsy reports of Marylanders who died in police custody during Fowler’s tenure.

On Twitter, Frosh heralded the conviction of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin as a win for justice.

“Systemic problems with policing & with equal justice require reform,” Frosh wrote after the jury delivered its verdict. “MD has taken steps to improve the quality of policing & the quality of justice. Work remains to be done. Our office is committed to continuing that work.”

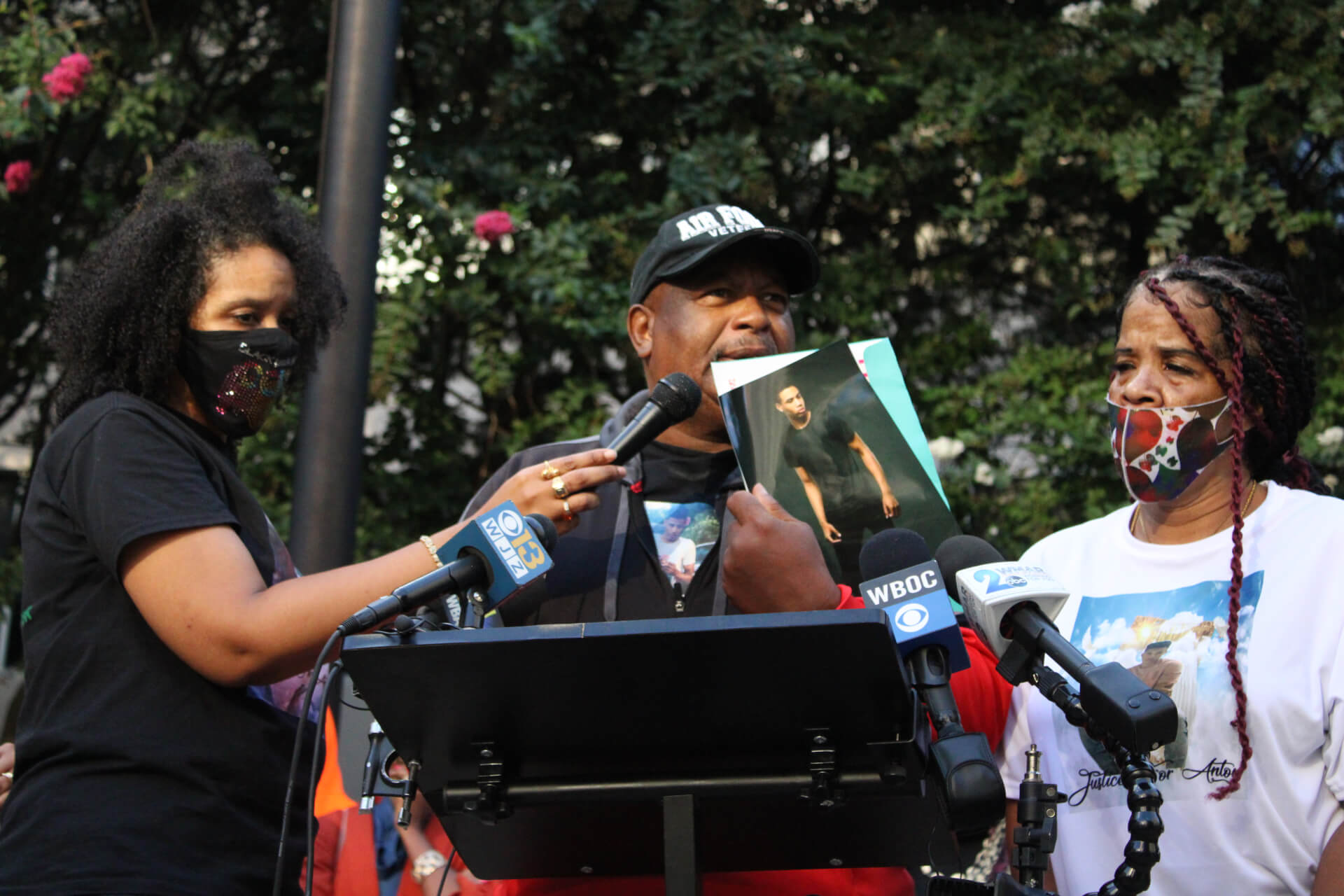

But the attorney general has received criticism from civil rights advocates, who note that he is representing Fowler in a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the family of Anton Black, a 19-year-old killed in police custody on the Eastern Shore in 2018.

The Black family said that Frosh is actively “fighting against … not with them” in their pursuit of accountability, particularly when it comes to his representation of Fowler.

Like Floyd, Black was subdued under the weight of law enforcement officers for several minutes before he died.

We watched the life being crushed from #GeorgeFloyd in slow motion, over 9 ½ minutes. This verdict confirms what every person who watched the video already knew. We hope that this verdict brings a small measure of relief to Mr. Floyd’s family.

— Brian Frosh (@BrianFrosh) April 20, 2021

“Anton Black died as a direct result of police restraint and use of force, but because Dr. Fowler’s office refused to acknowledge that Anton’s death was a homicide, his family has been forced to fight to even have his death acknowledged,” the Black family said in a statement issued last month. “In this moment, AG Frosh must acknowledge the eerie and terrifying similarity between the police murders of George Floyd and of Anton Black and act to ensure accountability is finally served on the officers who killed Anton and the medical examiners who covered up for them.”

Under Maryland law, state employees and institutions can apply to be represented by the attorney general in civil suits.

Frosh spokeswoman Raquel Coombs said that this leaves his hands tied regarding his representation of Fowler.

“The Office of the Attorney General is also charged with representing state agencies and employees who are sued for actions taken within the scope of their employment,” she wrote in a statement.

But civil rights attorneys in the state disagree, bringing a different interpretation of the law to the table.

“It is not the case that the attorney general is required, ever, in any circumstance to defend any particular officer or any particular piece of misconduct,” Cary Hansel, a civil rights attorney, told Maryland Matters.

‘In his sole discretion’

Under state law, police officers or state employees must submit written requests to receive representation by the attorney general’s office. Upon receipt of a request, the case is investigated to determine whether the requestor was acting within the scope of their duties or if the act that spawned the suit was perpetrated with malicious intent or in gross negligence.

According to Coombs, the Office of the Attorney General is “constitutionally bound to represent an agency or state employee” unless the investigation proves their ineligibility.

Hansel said that Frosh is “required” to deny representation in certain circumstances under the statute, but he also maintains the ability to pass cases off to special counsel or another private attorney.

“[The statute] provides that the attorney general has sole discretion in undertaking to represent the state officer or state employees,” he said. “So the decision, ultimately, is entirely up to the Attorney General at the end of the day.”

Maryland Matters reached out to Frosh’s office to ask about passing cases to private attorneys paid for by the state but did not receive a response.

If the attorney general’s office finds the requestor eligible for representation, under the law, it is then required to enter into an agreement that would make the officer or employee responsible for court and counsel fees and any damages if the judge rules that they:

- acted with malice;

- were grossly negligent;

- acted outside of the scope of their duties; or

- disclosed false or misleading information to the Attorney General’s office.

The officer or state employee would also be responsible for damages if a judge rules they are ineligible for the sovereign immunity defense.

Sovereign immunity caps the amount of money that plaintiffs are able to sue state entities for damages, currently $400,000 per claim.

Under the Maryland Police Reform and Accountability Act of 2021, that cap will be raised to $890,000 in 2022.

The attorney general also retains the ability to decline representation if the public employee has access to another lawyer or is covered by insurance that would provide an attorney.

Coombs maintained that those are the only scenarios under which Frosh’s office can deny representation.

Should he choose to represent a party accused of misconduct, state law also provides that Frosh can set terms of representation under an agreement which may include “any other provisions” that he “considers necessary.”

“Not only is it not the case that he has to get involved …if he does it, he can do it on his own terms,” Hansel told Maryland Matters in a phone interview. “So he could put a provision in, for instance, that says, ‘If I determine later that you’ve committed misconduct, if I determine later that … I find it morally reprehensible to represent you,’ that kind of thing. He can put that in there.”

Maryland Matters reached out to Frosh’s office to inquire about the provisional aspect of a representation agreement but never received a response.

Hansel said that Frosh’s ability to deny or pass off representation is “important to understand in the context of looking at the attorney general’s professed concern for police reform …because the attorney general in Maryland is absolutely free — in every case, in his sole discretion — to completely refuse to represent bad cops, bad correctional officers or other misconduct — even when committed by the state.”

Hansel was particularly irked by Frosh’s tweet thread about Chauvin’s conviction last month, telling Maryland Matters that the attorney general has “routinely represented” officers accused of misconduct “and done nothing on behalf of victims, or to improve policing or reform correctional services in Maryland.”

During the 2021 legislative session, Frosh’s office submitted written testimony in support of several pieces of the Maryland Police Reform and Accountability Act of 2021.

You are literally the defense lawyer for bad cops. Every day, in dozens of cases across the state, you defend cops in civil rights cases brought by the victims of police misconduct. How can you possibly claim to be committed to reform? Shame on you.

— Cary Hansel (@HanselLaw) April 21, 2021

‘Isn’t justice always in the interest of the state?’

Hansel told Maryland Matters that this pattern didn’t start with Frosh’s administration.

And he’s not alone in this thinking.

Civil Rights Attorney Larry Greenberg said that if real, substantive change is going to happen, it needs to start with the state’s top leadership. But Greenberg also made it clear to Maryland Matters that the blame doesn’t rest completely in the actions of Frosh.

“This is power. Not one person,” he said.

Rather, Greenberg suggested that state politicians are more likely to performatively act rather than lobby for real change.

“If you were so concerned, step up to the plate and instead of tweeting, speak. Do real reform. Be progressive. Get out there — get ahead of this. Stop certain things from potentially going on, that can create worse habits,” he said. “And again it’s not just Brian Frosh. This goes far and wide in Maryland politics.”

Hansel said that this has “gotten worse” over time.

“But what I would tell you about that also is that the other attorneys general in Maryland who made similar arguments didn’t have the audacity to go on Twitter to announce that they understood that there are systemic civil rights problems in America and to publicly commit to working to resolve them, while at the same time denying any relief to the victims,” he said.

Hansel explained that “it’s one thing to represent your client’s interests in court,” but another to declare that you stand with victims when “you’re doing everything you can to use the full power of the state to deny any justice to victims.”

Asked how Frosh could be more progressive in his approach to civil rights while protecting the interest of the state, Hansel posed his own questions.

“The first question you have to ask is: What is the interest of the state? Right?” he asked. “Isn’t justice always in the interest of the state?”

Hansel brought up a case in which prison guards opened a cell door, allowing an incarcerated person to be stabbed approximately 30 times.

He said the attack is on video, but Frosh’s office fought in court against its public release.

“If I could show you that video, it would spark an enormous outcry and call for change and we could make a real difference,” he said, adding that the state sustained administrative charges against the guards for this incident, “but then didn’t do anything at all” to discipline them.

“I can tell you about it, verbally, but I can’t show you because I’m not allowed to release the video,” he explained. “That’s not in the best interest of the state.”

“Frosh’s office litigates cases with an us-versus-them mentality, and with this false idea that they are the government against or versus the people,” Hansel said. “And the first question in every case that comes into the office of an Attorney General with an appropriate mandate in mind would be ‘What is justice in this case and how can I get there?’ not ‘Is there some way to avoid justice?’”

Frosh’s office announced the review of in-custody death reports completed under Fowler’s leadership late last month.

Coombs said as the attorney general’s office is reviewing the autopsy reports, “we have taken steps to wall off those in our office who are representing the [Office of the Chief Medical Examiner] and its current and former employees, including Dr. Fowler, from those who might be involved in any review.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution