After a wave of protests and nationwide focus on police brutality and racism, Maryland legislators are rethinking disciplinary measures in public schools, particularly the role of uniformed officers in schools.

House Bill 522 would expand the required training for assigned police in schools, called school resource officers, to include restorative approaches. Local school systems would also have to adopt a behavioral health and safety action plan before assigning school resource officers to schools.

Legislators need to “make sure [students] have the behavioral health supports that they need so that they aren’t suspended and suspended again…we need more restorative practices and more restorative approaches,” Del. Alonzo T. Washington (D-Prince George’s), the bill sponsor, told the Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee on Tuesday.

School resource officers may still arrest and search students under this proposal, but will be subject to more restrictions — they would not be able to enforce discipline except to prevent or intervene a situation in which a “serious bodily injury with an imminent threat of serious harm” is at stake. All school resource officers must pass a background check that shows no history of excessive force.

If the bill passes, local school systems could use grants that are allocated solely for school resource officers for behavioral health services. Additionally, $100,000 from the governor’s annual budget would fund a study on the school-to-prison pipeline.

In a behavioral health action plan, local school boards would have to measure the number of student arrests and expulsions for nonviolent behavior, as well as lay out steps to strengthen restorative and trauma-informed approaches.

However, some advocates contended that no amount of school resource officers is good for schools.

Amity Pope, a mentor teacher in Prince George’s County Public Schools, argued that medical professionals are still in the process of understanding students with ADHD, who often experience mood swings and “emotional outbursts.” So, the idea of training school resource officers to address developmental disabilities “is a little bit outlandish,” she said.

Children with developmental disabilities would not be able to learn to self-regulate, but would be punished for having a disability under this measure, Pope said.

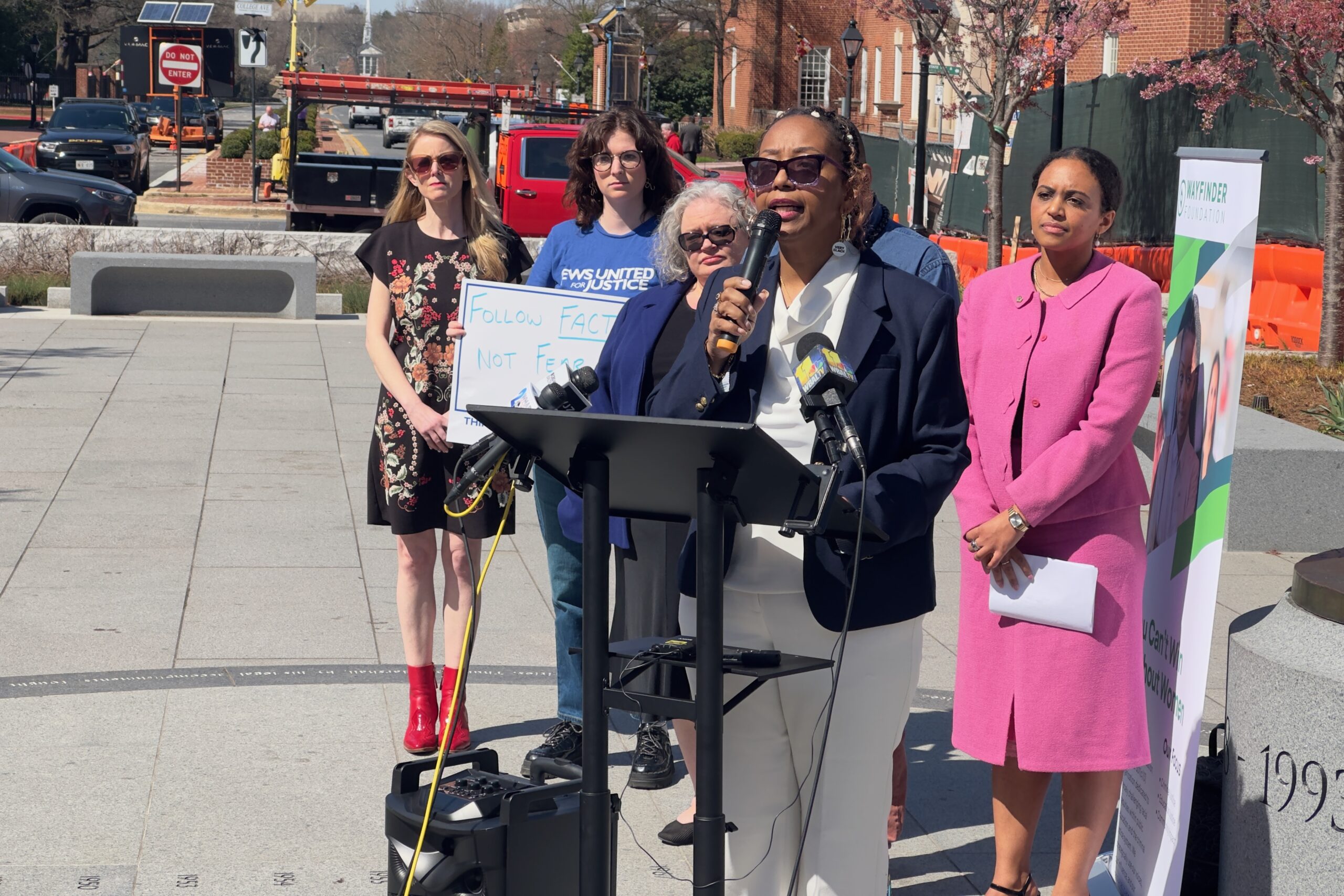

Zakiya Sankara-Jabar, the executive director of Racial Justice Now, a grassroots organization focused on dismantling structural racism in education, said that Washington’s bill does not go far enough in discouraging police presence in public schools.

Black students make up more than half of the arrests on school grounds in Maryland, Sankara-Jabar said. A bill that leaves school resource officers in schools will continue to disproportionately impact Black students, she continued.

Some advocates who testified brought up recently released body-camera footage that showed two Montgomery County police officers berating a 5-year-old boy who walked away from class last year. “I hope your momma let me beat you,” one officer said.

“A five-year-old Black child experienced police brutality here in this county — that is unacceptable,” Sankara-Jabar said. ”We cannot continue to allow Black children to be disposable in the state of Maryland.”

“I’m scarred by looking at that,” Tina Dove of the Maryland State Education Association echoed.

Dove supported Washington’s measure but proposed to double the hours of training for school resource officers and to require them to go back to training when new modules are added.

Sen. Mary Beth Carozza (R-Lower Shore) questioned the idea of weakening school resource officers’ authority and referred to the school shooting in Southern Maryland two years ago.

A month after the shooting at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida that killed 17 people, Sen. Katherine A. Klausmeier (D-Baltimore County), introduced the Maryland Safe to Learn Act of 2018 to increase security at all public schools.

Just before the Senate Budget and Taxation Committee heard Klausmeier’s bill, a teen at Great Mills High School in St. Mary’s County fatally shot one student, injured another and killed himself. A school resource officer at the campus confronted the gunman.

School resource officers “have been highly successful” in some local jurisdictions, Carozza said.

Washington countered that his bill does not weaken the role of school resource officers, but strengthens it by providing them additional training and more specific responsibilities. Local jurisdictions could continue to use the funding allocated to school resource officers under this measure, he added.

Washington’s measure passed the House of Delegates in a 93-42 vote last week.

In February, Dels. Jheanelle K. Wilkins (D-Montgomery) and Gabriel Acevero (D-Montgomery) introduced a legislative package seeking to restructure disciplinary measures in schools: the Counselors Not Cops Act, sponsored by Wilkins, which would reallocate the $10 million in state funding for school resource officers to mental health and behavioral health programs; and the Police Free Schools Act, sponsored by Acevero, which would prohibit school districts from contracting with local law enforcement agencies to station police officers in schools.

Sankara-Jabar said that Acevero’s bill is an example of a bill that goes just far enough.

Sen. Arthur Ellis (D-Charles) also introduced a bill that would have prohibited school resource officers from entering school buildings unless specifically instructed by the school or in response to an emergency involving violence.

None of these bills have advanced past their initial bill hearings.

The Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee also heard two other bills Tuesday pertaining to disciplinary measures in public schools.

House Bill 700, sponsored by Del. Sheila Ruth (D-Baltimore County) would remove students from criminal penalties in current law for disruptive, violent or threatening behavior on school grounds. Right now, anyone who violates these provisions could get fined up to $2,500, imprisonment up to six months, or both.

“I was shocked to learn that adolescents can be charged with a misdemeanor for acting up in school in ways that are typical adolescent behavior,” Ruth said. “Part of adolescence is learning impulse control and appropriate behavior, but the criminal justice system is not the answer.”

Ruth’s measure passed the House of Delegates in a 91-42 vote earlier this month.

House Bill 1166, sponsored by Del. Eric Ebersole (D-Baltimore and Howard) would require the Maryland State Department of Education to keep track of the number of students who are restrained or placed in seclusion, conduct a data analysis and make meaningful recommendations to reduce these interventions.

These interventions are disproportionately used with children of color and children with disabilities, according to Leslie Margolis, managing attorney with Disability Rights Maryland.

Currently, MSDE must report to the General Assembly on restraint and seclusion incidents, but does not further analyze the data and report the number of repeated incidents, for example, Margolis said. And the number of these incidents have not decreased over the years, she continued. This measure would require MSDE to develop an accountability system.

Ebersole’s bill sailed unanimously through the House of Delegates earlier this month.

“I think that ultimately…we’re going to view restraint and seclusion much the same way that we viewed corporal punishment many years ago,” Ebersole said.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution