As we celebrate Black History Month, we should remember to acknowledge the many accomplishments of African Americans during Reconstruction and, more importantly, commit to better teach this era in our public schools.

Traditionally, Reconstruction — the period between 1865-1877 when the states that had seceded during the Civil War were reintegrated back into the Union — has been glossed over in middle and high school. To the extent the period is covered at all, students learn only that “carpetbaggers” from the North flocked to the former Confederate states to swindle and otherwise take advantage of impoverished, recently vanquished southerners and that President Ulysses Grant was a corrupt incompetent chief executive.

The reality is that while Reconstruction lasted just 12 years, it was an important and, in part, successful effort to integrate Black people — many of whom were former slaves — into society.

During that time, the Fourteenth Amendment granting African Americans citizenship and equal protection under the law was ratified on July 9, 1868, establishing the basis for the Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling desegregating public schools. Less than two years later, the Fifteenth Amendment giving Black people the right to vote was ratified and the Civil Rights Act of 1875 prohibited racial discrimination in many public places such as restaurants and public transportation. (Interestingly, although the Maryland General Assembly voted against ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment, one of the largest celebrations of the measure’s adoption was in Baltimore.)

Historians estimate that during Reconstruction between 1,500-2,000 African Americans served in myriad public positions, ranging from local offices to state legislatures, statewide offices such as secretary of state, treasurer, lieutenant governor, and governor, and as U.S. representatives and senators.

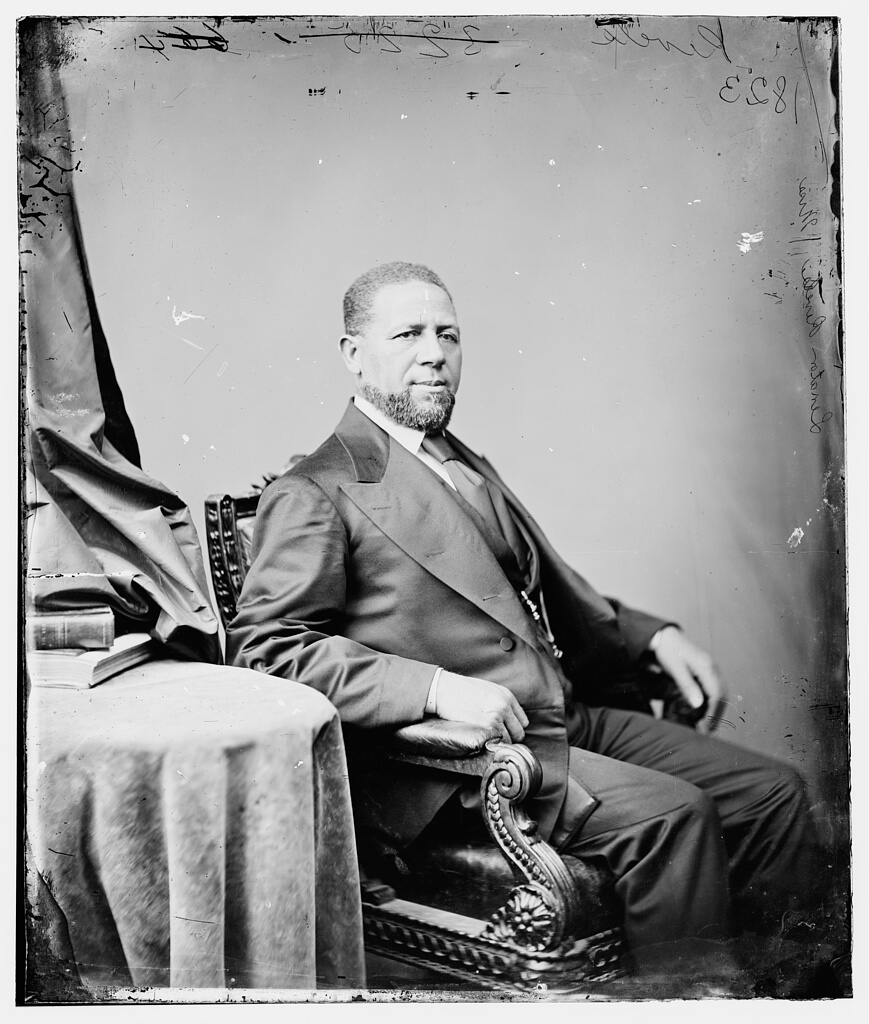

Many of those were milestone elections and appointments. For instance, in 1868, 88 of the 155 members of the South Carolina General Assembly were African American, making it the first state legislature with a Black majority. In October 1870, Congressman Joseph Rainey from South Carolina became the first African American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives. More than a dozen other Black members were elected to the House during Reconstruction.

Republicans Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce from Mississippi were the first two Black U.S. senators, serving from 1870-1871 and 1875-1881, respectively. In December 1872, Louisiana Republican Pickney Benton Stewart Pinchback advanced from his lieutenant governor position to become the country’s first Black governor.

Unfortunately, Reconstruction ended shortly after the election of 1876, ending a time of incredible racial progress. Shortly thereafter, court rulings either undermined, helped circumvent or struck down the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, paving the way for Jim Crow laws and 70-plus years of discrimination and segregation.

Not only is it important to ensure that Maryland school children learn about the achievements of the groundbreakers mentioned above and the many other trailblazing Black Americans during Reconstruction, but it is also crucial to teach students how Reconstruction was implemented and why it ended before reaching its goal of fully including Black people as equal citizens.

Thankfully, the opportunity to better educate Maryland students about Reconstruction exists in the form of a pending Maryland bill that requires the State Board of Education to develop content standards for African American history to be included in the overall state standards in social studies.

Introduced by Delegate C.T. Wilson (D-Charles), House Bill 11 mandates that the content standards include “the history of African people before conflicts that led to slavery; the contributions of African Americans to society, slavery and abolition; Jim Crow laws; the 1921 Tulsa race massacre; and social injustice and police brutality.”

While the measure as written is a good start to significantly upgrading the teaching of Black history in Maryland public schools, Delegate Wilson should add a provision to the bill requiring that Reconstruction be part of the content standards developed by the State Board of Education. This improvement to the bill corrects a longstanding shortcoming of Maryland’s history curriculum and ensures children that go through Maryland’s public school system are more familiar with an often overlooked but significant time period.

— GENE HARRINGTON

The writer, a lifelong Marylander, lives in Ellicott City.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution