Advocates Favor Single-Issue Policing Bills. How Do They Differ From the Speaker’s Omnibus Legislation?

Following the spate of tragedies that 2020 brought to the national stage, many lawmakers are saying that the 2021 General Assembly session is the year of police reform.

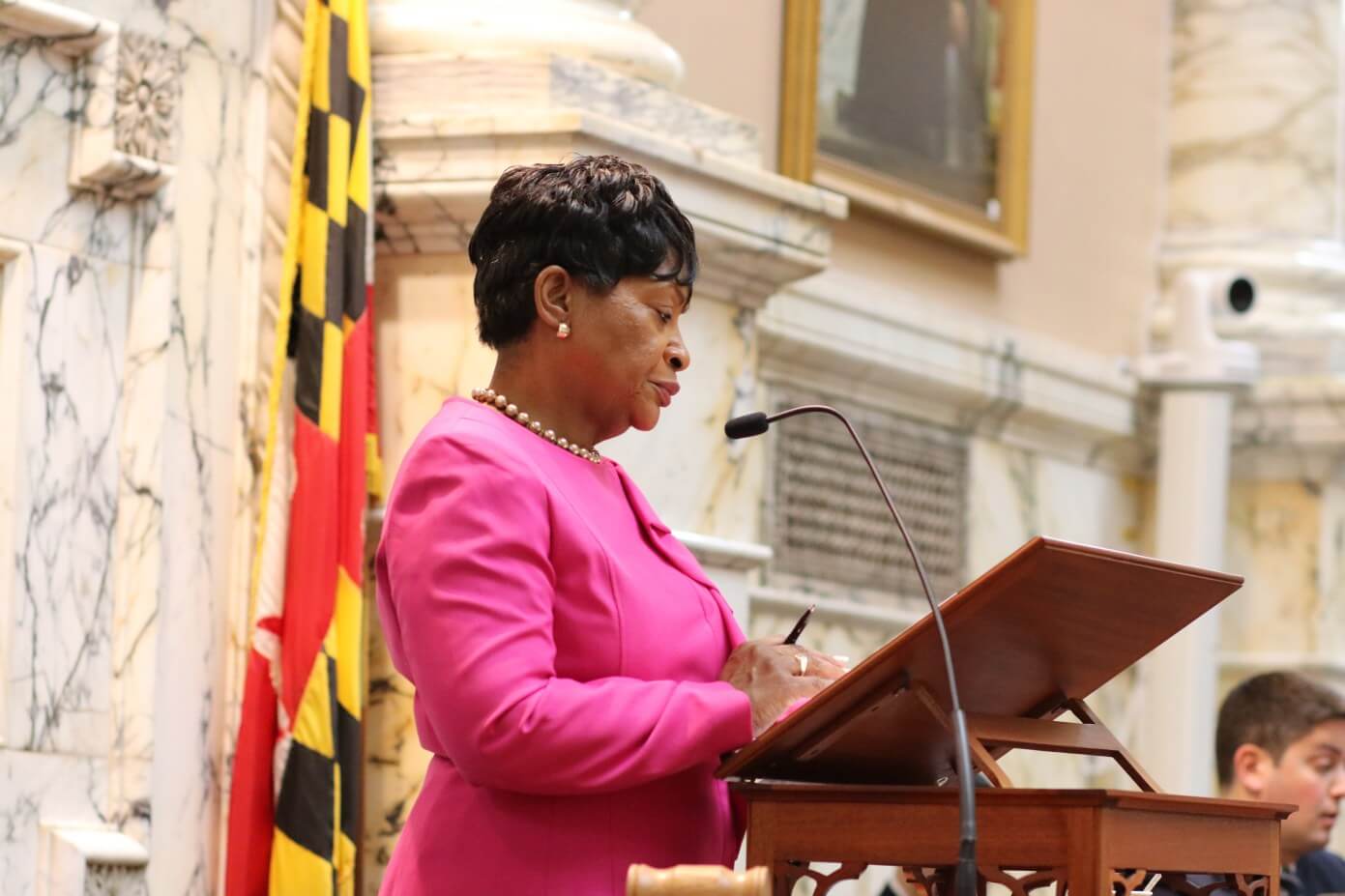

“It is horrifying that it took the death of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Rayshard Brooks, to bring attention to these issues across the country,” said House Speaker Adrienne A. Jones (D-Baltimore County). “We need to make structural reforms to the way we police in Maryland, not because we want to punish every individual police officer, but because we want to empower the public and community to take better control over this public investment and make their own decisions about the ways we keep neighborhoods safe.”

Jones is sponsoring a comprehensive piece of legislation that seeks to alter police practices from every angle. But advocates reject the bill, opting instead to rally behind smaller, single-issue bills, including measures to remove police officers from public schools, return control of the Baltimore Police Department to the city, repeal the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights, implement a statewide use of force statute and achieve greater transparency in state and local departments.

“While we support the general intent and direction of HB 670 [Jones’ bill] and applaud the speaker for opening the door to reimagining what police accountability might look like by repealing the LEOBR, the ACLU of Maryland and the coalition of more than 90 organizations we are working with … regrettably cannot support this bill as written,” David Rocah, a senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Maryland, stated during the hearing on Jones’ legislation last week.

“It is unfortunate that these issues have divided the House — Democrats from Democrats and Democrats from Republicans — when our ultimate goal is the same: equal treatment for every Marylander; safe communities; public confidence of law enforcement to respect each of us and our neighbors in the same way, regardless of skin color, wealth, or gender,” Jones said.

With so many pieces of legislation moving through both chambers, it’s easy to get confused about who is trying to accomplish what. So Maryland Matters broke down portions of Jones’ omnibus bill to compare and contrast with other legislation seeking to accomplish similar goals.

Re-establishing local control of the Baltimore Police Department

Baltimore City is the only jurisdiction in Maryland that doesn’t regulate its own police department.

Under Jones’ bill, the jurisdiction of the Baltimore Police Department would be returned to the mayor and city council on Oct. 1, 2021.

Del. Melissa R. Wells (D-Baltimore City) and Sen. Cory V. McCray (D-Baltimore City) have cosponsored similar legislation on behalf of the administration of Baltimore City that would create an advisory board to investigate any problems that could arise from the agency’s transfer.

Following the submission of the advisory board’s report, the city would have to pass and ratify a charter amendment in 2024, which would allow the mayor and City Council to amend the law and officially take control of the department in 2025.

McCray’s bill is backed by the Maryland Coalition for Justice and Police Accountability.

The ACLU of Maryland testified in its favor earlier this month, but submitted proposed amendments to include more civilians on the advisory board and move the charter amendment up to 2022 and the transfer of control to 2023.

Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee Chairman William C. Smith Jr. (D-Montgomery) told McCray that the committee plans to fold his legislation into its Maryland Police Accountability Act of 2021 package.

Limiting no-knock warrants

The efficacy of no-knock warrants was called into question nationally following the death of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky., last March.

Jones’ omnibus bill seeks to limit law enforcement’s use of these warrants by requiring officers to present “clear and convincing evidence” that there is imminent danger in their search warrant applications.

Additionally, unless there is an emergency, officers would be prohibited from executing search warrants between 7 p.m. and 8 a.m.

Sen. Jill P. Carter (D-Baltimore City) presented legislation to eliminate no-knock warrants during three days of interim bill hearings held by the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee in the fall.

During the bill’s official 2021 hearing last month, Carter said that no-knock warrants “don’t really serve any legitimate purpose” and “cause more harm than good” because people inside of their homes are put on the defensive when they don’t necessarily need to be.

“Even with a knock, officers don’t have to wait a period,” she said. “A requirement of a knock doesn’t require that an officer actually knock and then necessarily wait an exorbitant amount of time, but simply to put people on notice that they are coming into the house.”

Del. Robin L. Grammer (R-Baltimore County) presented legislation before the House Judiciary Committee earlier this month that also looks to do away with no-knock warrants.

Giving more teeth to the Maryland Police Training and Standards Commission

In the early days of the House Workgroup to Address Police Reform and Accountability in Maryland, last summer, members declared that the Maryland Police Training and Standards Commission was “without teeth” when it comes to enforcing policing policy.

Jones’ bill would delegate a lot more responsibility to the agency, including:

- Mandating that it creates a training program for citizens appointed to sit on the commission;

- Holding police departments accountable when they violate the use of force statute created under this bill;

- Working with the Governor’s Office of Crime Prevention, Youth and Victim Services to withhold state funding from agencies that violate the use of force policy;

- Revoking an officer’s certification for violating the use of force statute, being convicted of perjury or a felony crime or resigning or being fired from their department during a misconduct or use of force investigation;

- Creating a database to track officers who have been decertified for using excessive force; and

- Designing an implicit bias test and training sessions to be used by agencies statewide during the hiring process.

Other lawmakers have their eye on reconfiguring the commission’s responsibilities, too.

Sen. Charles E. Sydnor III (D-Baltimore County)

Sen. Charles E. Sydnor III (D-Baltimore County) is sponsoring a bill that would require the Maryland Police Training and Standards Commission to keep a database of officers who have received formal misconduct complaints and what, if any, punishment was administered.

Additionally, the legislation would mandate state’s attorneys in each jurisdiction to keep a running list of police officers who were alleged to have been dishonest or committed perjuries.

Certain records from the database and state’s attorneys’ offices would be available to the public.

Sydnor’s bill will be heard in the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee Wednesday.

Wells has put forth legislation that would order the Maryland Police Training and Standards Commission to require police training academies to include implicit bias tests, training and evaluations for entry-level officers. It would mandate similar tests and training for public defenders.

Wells’ bill will be heard in the House Judiciary Committee Tuesday.

Jones’ legislation would also order the Maryland Police Training and Standards Commission to require that officers undergo mental health assessments in order to be recertified.

Some lawmakers have put in bills that would require not only assessments but support services if an officer finds that they are struggling with their mental health.

Sen. Michael A. Jackson (D-Prince George’s) will present a bill Tuesday that, among a series of other measures, would create a confidential mental health hotline through the commission that would give officers referrals to counseling services.

Sen. Mary L. Washington (D-Baltimore City) brought a bill before the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee last month that would order all police departments to offer an “employee assistance” mental health program that officers could access at little-to-no cost.

Independent investigations

The House omnibus bill has a measure that would require incidents that end in death or serious injury to be investigated by an independent body, but does not establish what agency would be responsible for completing the investigation.

Late last month, House Judiciary Committee Vice Chair Vanessa E. Atterbeary (D-Howard) told Maryland Matters that members of the Workgroup to Address Police Reform and Accountability in Maryland couldn’t agree on where the investigatory power should lie: Democrats seemed content with having the Office of the Attorney General oversee misconduct investigations; noting that is a political position, Republicans disagreed.

Taking a similar position as the committee’s Democrats, Smith is sponsoring a bill that would designate Attorney General Brian E. Frosh (D) as the independent investigatory body. If his office recommends prosecution in its final report, the jurisdiction’s state’s attorney has 45 days to notify whether or not they plan to proceed with a trial. Otherwise, the officer would be prosecuted by Frosh.

Use of force

The workgroup’s bill has an expansive use of force statute that would order law enforcement officers to:

- Attempt to de-escalate aggressive situations without using force;

- Intervene when they see other officers using excessive or unnecessary force;

- Call for medical assistance and provide first-aid to people injured during interactions with police;

- Document all use of force incidents that they observed or participated in; and

- Undergo training sessions to learn less-lethal techniques.

Additionally, officers would be prohibited from shooting at moving vehicles unless they are being used as a weapon or from using chokeholds and neck restraints.

Jones’ use of force statute would also require supervising officers to respond to the scene where the incident occurred and review any video recordings.

Under the bill, anyone who knowingly violates the statute would be guilty of committing a misdemeanor crime and subject to between five and 10 years in prison.

Sen. Jill P. Carter

There are several bills that take on different aspects of this multi-faceted policy, including legislation cosponsored by Carter and Del. Debra M. Davis (D-Charles) that would require officers to exhaust all alternative tactics before force is used.

If an officer needed to use force, they would be required to stop when the person was under control or no longer posed a threat. All instances of force would be independently evaluated.

Additionally, law enforcement officers who use lethal force may be charged with murder or manslaughter. Officers who use force that results in serious injury could be charged with assault or reckless endangerment.

Davis’ bill is backed by the Maryland Coalition for Justice and Police Accountability, which includes the ACLU.

Carter is also sponsoring a bill that would require officers to make a “reasonable attempt” to intervene when they are witnesses to excessive force by fellow officers.

Taking Carter’s bill a step further, Sydnor presented legislation last month that would mandate that officers report actual knowledge of excessive and unnecessary force to their supervising officer or chief.

The Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights

Perhaps most controversially, Jones’ bill seeks to repeal the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights in its entirety.

The Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights provides due process protections for officers during investigations that could result in demotion or dismissal and lays out a uniform procedure for misconduct investigations across the state’s 148 police departments, preempting local laws.

Advocates say the statute makes misconduct investigations too opaque and provides protection for police officers that other public employees don’t have.

According to activist and Project Zero cofounder DeRay Mckesson, Maryland is one of 21 states that still has the statute.

Police reform advocates and law enforcement representatives have sparred for years over whether or not the state should toss the measure and what should replace it if it goes.

The omnibus bill would order state and local agencies to create and publish a new “open and transparent” disciplinary process that includes administrative charging committees that have trained civilian members.

Under Jones’ bill, once the complaint is investigated, the administrative charging committee would examine the findings, determine if the officer should be administratively charged and, if so, recommend a disciplinary measure to the department’s chief.

Officers who have received a probation before judgment for any crime would be ineligible to appear before the administrative charging board. Chiefs would determine their discipline instead.

There are two other stand-out bills that also seek to restructure the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights: One sponsored by Del. Gabriel Acevero (D-Montgomery) that would do away with the law entirely and another sponsored by Carter that would alter the disciplinary process for law enforcement agencies across the state.

Backed by the Maryland Coalition for Justice and Police Accountability, Acevero plans to establish a replacement disciplinary process through amendments.

Carter’s bill would mandate that the department’s chief review all of the findings from the investigation, give the accused officer information about the investigation and recommended disciplinary action and allow them to object to the findings.

Under this legislation, jurisdictions would be given the ability to create civilian oversight boards, which would take on the responsibilities of the chief during the investigatory and disciplinary process.

Chiefs or their designees would have the ability to reassign officers or suspend them without pay.

Should a chief feel that there are contested facts in the investigatory record, they would be able to call a hearing. After the hearing, the hearing officer would write and submit proposed findings of facts to the chief who would then decide the disciplinary action.

In most circumstances, officers would have the ability to appeal the chief’s or oversight board’s decision in the circuit court.

As with Jones’ bill, officers aren’t entitled to hearings if they have received a probation before judgment for a crime but can appeal to the circuit court.

Carter’s legislation is being amended in the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee this week.

During a voting session last week, Sen. Jack Bailey (R-St. Mary’s) took issue with restructuring the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights at all.

Sen. Jack Bailey (R-Calvert, St. Mary’s)

“I’d just like to say that, quite frankly, on the record, I do not believe that the entire state of Maryland is reaching out and screaming about police reform,” Bailey, a retired Maryland Department of Natural Resources police officer, asserted. “This is not a topic in my district.”

He continued, saying that Maryland’s police standards are “much higher” than other states.

“It is important that we recognize that,” Bailey explained. “And I think to blanket this — to say we need police reform for the way that the people are being treated by one or two examples, I think, is atrocious to the fact that these people are the ones that are willing to give their life every single day for the safety of our citizens.”

According to the Mapping Police Violence Database, 145 people have died during police encounters in Maryland between 2013 and 2021. One person, Kwamena Orcan, has already died during an interaction with Gaithersburg police officers this year.

Sydnor responded by saying that police accountability isn’t an issue specific to Baltimore City or Prince George’s County, detailing a time he was stopped by an officer in Virginia for “going too slow,” or when he was pulled over in Baltimore City because he went through a yellow light.

“I knew what that was about. I know exactly what that was about,” he said. “So, it’s with those kinds of incidents that I believe a lot of the advocates are pushing for this reform.”

“I believe there should be due process and that people should be treated fairly and the like,” Sydnor continued. “But again, I think the incidents that have happened have shown us that there is some sort of cancer that exists and that this system the way it has been played out is not fair.”

Body cameras

Jones’ bill would require all police agencies in the state of Maryland to use body cameras by 2025.

Last week, Del. Julian Ivey (D-Prince George’s) presented legislation before the House Judiciary Committee that would require all law enforcement agencies in the state to issue body cameras to on-duty officers by Oct. 1. During that same hearing, Del. Brian M. Crosby (D-St. Mary’s) brought a bill that would require the Department of State Police to give body-worn cameras to all on-duty officers by 2022.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution