Health Officials Work to Overcome ‘Understandable’ Vaccine Hesitancy

When officials in Prince George’s County began preparing for the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines late last year, they knew that many residents would hold back.

They knew that many people in Maryland’s largest majority-Black jurisdiction would not seek out an appointment. Nor would they accept a vaccine if a shot was offered to them.

In the weeks since vaccines started to become available, health care workers, first responders, teachers and others have been among those displaying what officials now refer to as “vaccine hesitancy.”

The root of the refusal to embrace the vaccines flows from a deep-seated distrust of the government, borne of centuries of mistreatment, neglect, and worse, public health and elected leaders say.

Those leading outreach efforts in Prince George’s didn’t need to consult history books to learn about the federal government’s decades-long failure to provide penicillin to men in Tuskegee, Ala., who were known to have syphilis, or Johns Hopkins Hospital’s appropriation of Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells for scientific research without her knowledge or consent.

Or any of the countless indignities and denials that marginalized people have suffered.

They only needed to open the pages of their family photo albums.

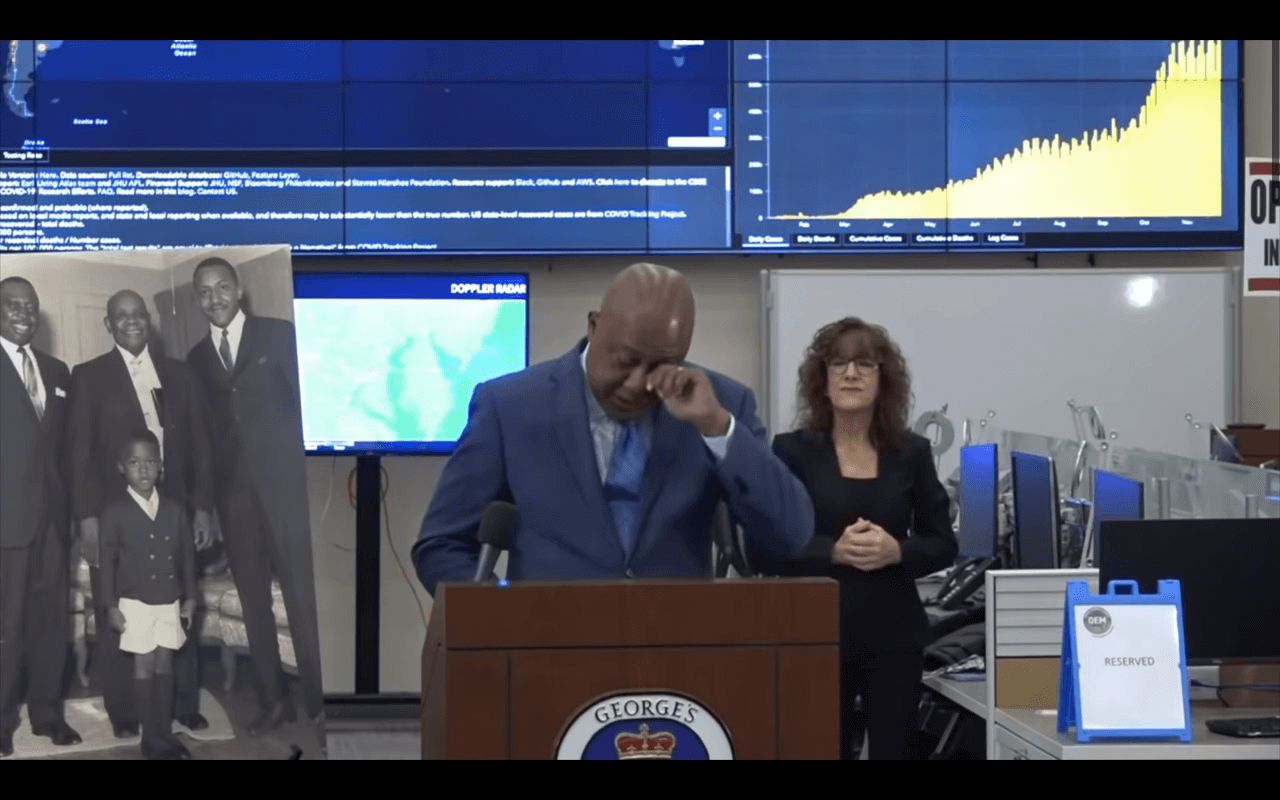

On Dec. 10, George L. Askew, the county’s Deputy Chief Administrative Officer for Health, Human Services and Education, showed reporters a photo that was taken in his native Cleveland when he was a child.

Behind him in the black and white image are his father, George Andrew Askew Jr.; his grandfather, George Andrew Askew Sr.; and his great-grandfather, the Rev. Noah Askew.

Rev. Askew’s father was a slave in North Carolina.

“The voices of these men, from slavery to today, ring in my ears,” Askew said, pausing repeatedly to wipe away tears. “Their stories of — and eyewitness to — their struggle, oppression, denied access and marginalization, and my own, are part of who I am and what I believe.”

“And I can tell you, not once in my lifetime, did any of these men say to me, ‘hey, trust in your government, they will always do what’s in your best interests,’” Askew added. “Nor did they ever say, ‘Never question what the The Man is asking you to take, eat or inject.'”

Two months to the day after those remarks, state and local health officials are battling multiple issues in their efforts to vaccinate as many people as possible against the coronavirus. Chief among them are a severe shortage of doses and a reluctance among many people of color to get vaccinated.

When he toured Baltimore County’s large-scale vaccination site in Timonium on Monday, Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) told Executive Johnny A. Olszewski Jr. (D) that state health personnel placed calls to 2,000 Prince George’s residents prior to the opening of the Six Flags America mass-vaccination site last Friday. The names had been provided by the county health department.

Only 75 appointments resulted from those calls, said the governor, seemingly frustrated by the response.

The opening of the Six Flags site and another at the Baltimore Convention Center attracted widespread media coverage, and the governor’s office said this week that hundreds more Prince George’s residents have come forward to get vaccinated.

But local leaders, including Prince George’s County Executive Angela D. Alsobrooks (D), know that the broader challenge remains. The county has launched a campaign called “Proud to be Protected” in affiliation with local hospitals and non-profits.

On Monday she hosted a web chat with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in an effort to tackle some of the rumors and misinformation that is keeping some people home.

During the 20-minute conversation, Fauci was asked to reply to the questions local health officials hear most often from the public, among them:

- “This vaccine has been developed so quickly, how do we know that it’s safe and effective?” (Fauci’s answer: The vaccines have undergone rigorous testing and are safe.)

- “Is it possible to get COVID-19 from the vaccine?” (Answer: “It’s impossible to get COVID-19 from the vaccine.”)

- “Why do I need to get a shot?” (Answer: Because COVID-19 can be fatal.)

Fauci called it “understandable” that people of color would have a concern about “engaging in a medical program that is run by the federal government.”

“But the ethical safeguards that have been put into place, since Tuskegee and since the Henrietta Lacks incident are such that those types of things would be impossible under today’s conditions,” he said.

Hogan and Baltimore Mayor Brandon M. Scott (D) launched a public confidence campaign, featuring high-profile Black leaders two weeks ago. A public service announcement touting the safety and importance of the vaccine is now running on local radio and television in the Baltimore media market.

In addition, Hogan has asked Brigadier General Janeen Birckhead of the Maryland National Guard to lead a “Vaccine Equity Task Force.”

On Wednesday, Scott and Baltimore Health Commissioner Dr. Letitia Dzirasa announced a new partnership also aimed to boosting confidence in the vaccines.

The initiative will ensure that “residents in communities hardest hit by COVID-19 hear from their neighbors and trusted messengers in their communities about the importance of getting the vaccine when they are able and to combat myths and misinformation about the vaccine,” Scott’s office said in a news release.

Morgan State University, the Maryland Institute College of Art Center for Social Design, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s International Vaccine Access Center are all participants in that effort.

“Forging new partnerships that lead to innovation in outreach and education are a major step in this critical fight to understand access issues and to address vaccine hesitancy among different segments of our population,” Scott said.

Despite these efforts, Askew, the top health official in Prince George’s, recognizes the steep climb that remains.

As he finished his remarks on Dec. 10, he said: “What I will assure you, as a public health and government official here in Prince George’s County, is that we will always work our hardest to promote, enhance and preserve the health and well-being of all Prince Georgians.”

“I am urging you, when the vaccine becomes available to you, join us in taking the vaccine and being proud to be protected.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution