2020 in Review: 44 Years After Jerry Brown’s Improbable Md. Primary Victory, Here’s the Back Story

Editor’s note: Between now and Jan. 3, we’re re-running 12 great articles that appeared in Maryland Matters in 2020, in chronological order. On Jan. 4, we’ll provide links to our best-read stories of the year. These are the stories you made possible by supporting our independent nonprofit newsroom. You still have time to make a tax-deductible contribution before year’s end.

This column from Frank A. DeFilippo, which first appeared on May 18 with the headline “44 Years to the Day After Jerry Brown’s Improbable Victory in the Md. Primary, Here’s the Back Story,” dives deep into the inside story of Jerry Brown’s Maryland campaign for president in 1976.

Copyright @ 2020 by Frank A. DeFilippo

Biographies are tricky. So are their reviews. That’s especially true if one is read and the other is not. This instance involves Molly Ball’s “Pelosi” and Joe Klein’s review in The Washington Post two Sundays ago. Klein supplied the Cliff’s Notes for the book.

Or, no, but I saw the movie.

So, having read someone else’s impression and not knowing what’s really in the book, here’s the inside story of Jerry Brown’s Maryland campaign for president in 1976, the launch point of Klein’s review.

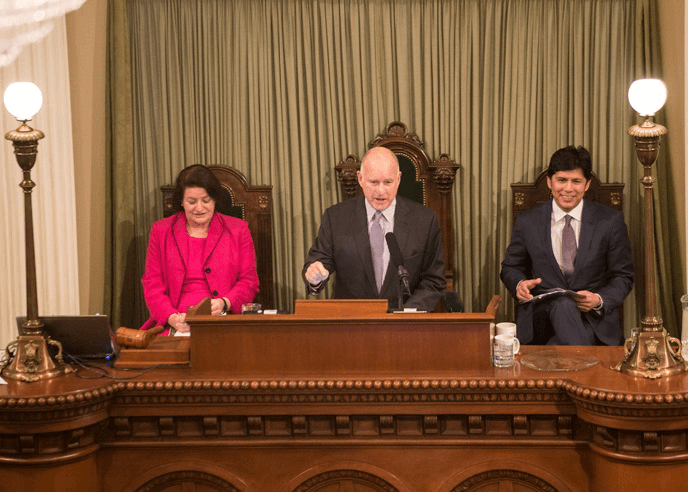

Home-schooled since childhood in the face-to-face business of precinct politics, Pelosi, according to Klein’s rendition of Ball’s book, assembled the machinery that handed Brown one of his major victories that year.

“This particular machine was led by former Baltimore mayor Tom D’Alesandro, who was Nancy Pelosi’s brother and Baltimore County Executive Ted Venetoulis, who had been Pelosi’s high school boyfriend,” Klein wrote.

Yes, but. . . .

The machine that Klein (and Ball) speaks of was a rare symbiotic alignment of Maryland’s Old Guard and Young Turks, each flank of the Democratic party using Brown as a vehicle for its own interests – D’Alesandro and Venetoulis to advance Brown’s candidacy as a favor to Pelosi, and Gov. Marvin Mandel to teach Jimmy Carter a lesson in loyalty.

Pelosi had flown east from her home in California to join with her brother and Venetoulis in Baltimore on how best to help Brown’s quixotic quest for the presidency in Maryland. High on the list was a meeting with Mandel.

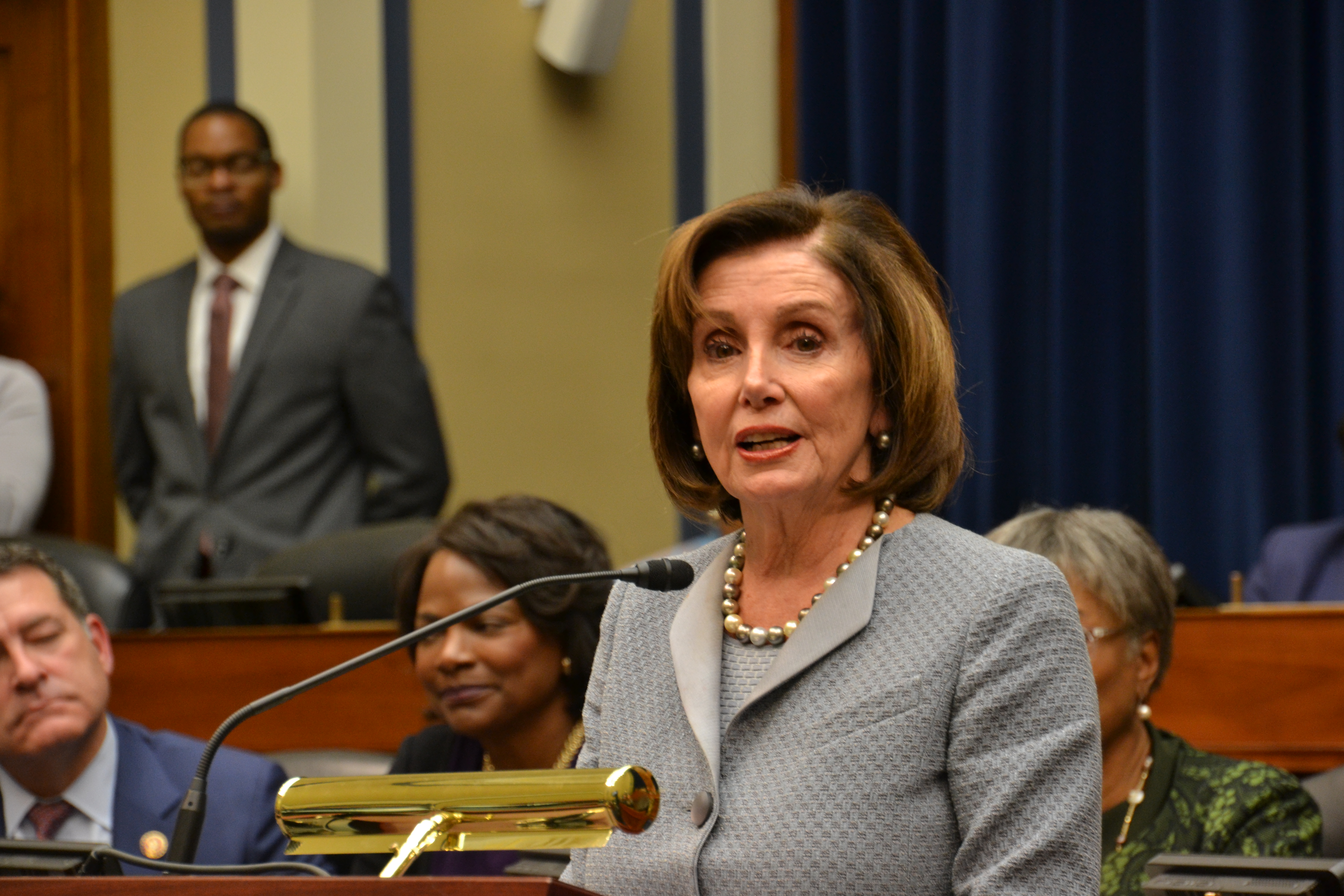

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.). Photo by Robin Bravender

They met with the popular governor at his office in Maryland’s antique State House in Annapolis, where an agreement, of sorts, was reached, straight-faced, with Mandel never revealing his true motive for agreeing to the joint venture, which he eventually would subsume as his own.

The direct contact person with the Brown campaign was Mickey Kantor, Brown’s manager, who later would become commerce secretary in the administration of President Clinton.

Frank A. DeFilippo

Mandel had already seized the idea of supporting Brown, prompted by conversations with Robert Strauss, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, who had his own subterfuge underway, and a phone call from Pat Brown, Jerry’s father and the former California governor, with whom Mandel was friendly from his years as Maryland House speaker and his friendship with his California counterpart at the time, the legendary Jesse Unruh.

Mandel’s contribution to the machinery of Brown’s campaign was, well, the machinery of the Maryland Democratic Party which, down to the lowliest court clerk, he controlled.

At the time, Mandel’s suzerainty of the state’s Democratic party was nonpareil. It radiated through the State House and the political clubhouse of Irv Kovens in Baltimore to every corner of the state – the General Assembly, Baltimore’s City Hall, the Democratic State Central Committee, nearly every county, and even warrens of the Republican Party through friendships and alliances in the legislature.

For openers, Mandel decided to assemble the live bodies that made up the so-called “organization” Democratic leaders, in those days labeled “muldoons,” a term of affection peculiar to Baltimore politics that denoted the concept of the extended family – those who could deliver the most votes in their wards or precincts through their prehensile connections — familial, business, political, friendships, paid poll workers, etc.

The assignment to arrange a breakfast meeting was handed to Maurice Wyatt, Mandel’s appointments (patronage) secretary and ambassador to the precincts, and himself the heir of one of Baltimore’s premier political bosses, Judge Joseph Wyatt, the senior partner in South Baltimore’s old Wyatt-Della organization.

One by one and two by two the check-listed guests arrived at the Hilton Hotel in downtown Baltimore, about 50 of the bosses, bosslets and elected officials from around the state, the only time in anyone’s memory that Maryland’s largely mythical political machine, gathered in the flesh and in the same room – Kovens, James H. (Jack) Pollack, Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., Thomas D’Alesandro 3d, state Sen. Harry McGuirk, Venetoulis, Lt. Gov. Blair Lee 3d, then-Senate President Steny H. Hoyer, Baltimore City Councilman Dominic “Mimi” DiPietro, Baltimore Mayor William Donald Schaefer, George Russell, Louis Grasmick, Peter O’Malley, Sen. Joseph Staszak, William “Little Willie” Adams and his sidekick and factotum Del. Loyal Randolph, Sen. Joseph Bertorelli, Sen. Jerry Connell, Secretary of State Fred Wineland, former Baltimore County executive Dale Anderson, to name a few of the roll call’s attendees and a family portrait of Maryland’s political machine, circa 1976.

Mandel issued an extraordinary party call – the first and only in any attendee’s memory — and delivered a “one for the Gipper” speech. He pitched Brown’s political ascendancy and laid out a case against Carter’s trustworthiness.

“Do me a personal favor. Do this for the Democratic Party,” Mandel said. “We don’t have any [walk-around] money this time, but I’ll make it up to you later on.”

The word went out. “Marvin wants. . . . “

Brown put on a brief but whirlwind campaign in Maryland, dazzling reporters and citizens alike with his Zen-Jesuit utterances. He demanded personal security from the same State Police bodyguard detail as Mandel, as he traveled light and without accompanying protection paid for by his home state of California.

Maryland picked up the tab, more out of caution after Gov. George C. Wallace had been gunned down on a Laurel parking lot in 1972. Mandel’s campaign funds also bankrolled the thousands of sample ballots that helped lead Brown to victory, a tactile reminder to voters that Brown was their leaders’ choice.

On the night of May 18, 1976, Mandel gathered with friends, political associates and staff members in a penthouse suite in the very same Hilton Hotel where the breakfast had been held.

As the results rolled in, Mandel had something to smile about. He had, once again, delivered Maryland, putting his personal appeal on the line. Brown had defeated Carter with 48% of the vote to Carter’s 37% – 284,271 votes to 217,166 — stalling Carter’s momentum with a series of state victories that began with Maryland and the state’s Democratic machine.

Brown had vanished from Maryland before election day, never to be heard from again.

On election night, when the results were in, Mandel tried to raise Kantor on the phone in California to discuss Maryland’s contribution to Brown’s campaign, and maybe even get a thank you. Kantor never took the call.

It was the cheapest election victory that was ever bought in Maryland — $250 worth of bacon and eggs.

And what was Mandel’s beef with Jimmy Carter? It was simply that Jimmy Carter was, well, Jimmy Carter.

So meet the real Jimmy Carter, the Jimmy Carter behind the smile, the Jimmy Carter who was grudgingly awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Jimmy Carter whom humorist P.J. O’Rourke described as a “pathetic old coot who pounds nails into poor people’s houses.” Carter’s earlier imprimatur as a “public moralist” from a doting Southern historian, Douglass Brinkley, was decidedly not reflective of his antics as governor of Georgia.

Enter the back rooms of Democratic politics, circa the 1970s, and view Jimmy Carter’s weasel factor through the eyes of his peers, the nation’s 35 other Democratic governors.

Former Gov. Marvin Mandel (D) at Government House in an undated photo. Photo from the collection of the Maryland Manual

At a late summer caucus in 1971, in the dank precincts of Miami, 36 Democratic governors gathered to elect a chairman of their newly swollen ranks. The unchallenged favorite was Marvin Mandel, at the time one of the country’s two Jewish governors. Welcome to the political arena of Georgia’s newly minted governor, Jimmy Carter. On the evening of the election, Carter was overheard saying on the phone that he couldn’t support Mandel because “I can’t sell a Jew in the South.”

To cover his broadly exposed butt, Carter engaged in an act of high sedition and low connivance. He endorsed the only other Jewish governor of the moment, Frank Licht of Rhode Island, a quiet and unassuming man who had never entertained the notion of aspiring to the chairmanship and who might have had difficulty delivering his own vote to himself.

But Licht ego-tripped to the idea while Carter feigned an attempt to round up votes, much to the chagrin of the other governors. Ultimately, Licht, seeing the handwriting on the ballots, dropped out. Mandel was elected unanimously, and a lifelong enmity was born between Mandel and Carter that would rumble like a thunderhead through a presidential election and a federal prison sentence.

Fast forward to April of 1973, to the evening before Nixon’s first significant Watergate speech. The Democratic governors assembled in conference at Lake Huron, Ohio, a mudflat on the outskirts of Cleveland, to schmooze over policy and navigate party strategy through Watergate and the associated scandals.

In attendance was Robert Strauss, then chairman of the Democratic National Committee and later a Washington uber lawyer, now deceased. Strauss was at Lake Huron for one reason: to dissuade the governors from adopting a resolution denouncing Nixon so he, Strauss, could possibly win a financial settlement for the Watergate break-in from the Republican Party. (The break-in actually occurred under Strauss’ predecessor as chairman, Lawrence O’Brien, on June 17, 1972.)

Carter went Strauss one better by asking the Democratic governors to adopt two resolutions – one expressing confidence in Nixon’s innocence and asking Americans to unite behind the president and to pray for him, and another praising FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover as a great American. Thus, the second face of Carter as the “public moralist.”

“Innocent,” bellowed Gov. Philip Noel of Rhode Island. “I think he’s a goddamned crook. Take your resolution and stuff it.”

The Carter resolution incident occurred after 20 of the governors in attendance accidentally discovered, one by one around the conference table, that each of them was being actively investigated by the Nixon Justice Department under Attorney General John M. Mitchell. Mitchell later acknowledged in an affidavit that at one time he had instructed the Justice Department to launch investigations against the 20 Democratic governors.

Both Strauss and Carter lost their cases big-time. The Democratic governors hooted Carter out of the meeting room and later adopted the anti-Nixon resolution. The next night Nixon delivered his infamous non-denial denial Watergate speech.

Among his peers, Carter was the most distrusted Democratic governor in the country. A case in point: In September 1973, the governor-members of the Southern Governors’ Conference gathered for their annual meeting at another waterside resort, in Point Clear, Ala. High on their agenda was the selection of a new chairman. At the time, Gov. Reuben Askew, Democrat of Florida, believed that he was in electoral trouble for pushing through a public accommodations law in his state.

Askew felt that the chairmanship of the conference of Southern governors would reaffirm his credentials as a Southerner despite his liberal leanings and his progressive record on civil rights. So he began quietly enlisting the support of his colleagues. Askew’s election was virtually assured. Carter was appointed to the largely ceremonial nominating committee that merely rubber-stamped backstage decisions. But Carter, true to form, belied the dictum that good politicians stay bought.

No sooner was Carter appointed than he immediately threw his support elsewhere, to the Texas governor of the moment, Dolph Briscoe, a stiletto-in-the-back maneuver that infuriated the other governors and ticked off Askew. So enraged were his colleagues that they drafted a letter of agreement and forced Carter to sign the understanding that he would abide by the nominating committee’s recommendation. Again, Askew’s enmity for his neighboring-state governor would carry over to the 1976 presidential election. However, Askew later accepted a federal appointment in the Carter administration as U.S. Trade representative.

Carter, after serving his mandated single term as governor of Georgia, began his underground campaign for president in 1975 by worming his way into the Democratic National Committee and double-dealing Democratic governors. He began pestering DNC Chairman Strauss to appoint him to a post within the DNC. Strauss finally weakened, and in a sense triggered the unintended consequence of launching Carter’s candidacy for president. Strauss appointed Carter as chairman of a committee raising funds to underwrite the campaigns of Democrats running for Congress. The position enabled Carter to travel to virtually every state in the country – with the cachet and portfolio of the DNC – to establish a personal fundraising network and collect chits for his future presidential campaign.

Next, Strauss bestowed upon Carter the title of liaison to the collective of Democratic governors. Among Carter’s first actions was to ask each of the Democratic governors for their personal polls so that, as he explained it, he could review the political life-scape in their states. Mandel refused to surrender his polls. So much for truth in packaging.

Former President Jimmy Carter. Official White House photo

During the February 1976 meeting of the National Governors’ Conference in Washington, D.C., Strauss and Mandel met for dinner at the legendary Duke Zeibert’s, a period-piece celebrity-table hangout of politicians, lobbyists, athletes and wanna-be-seens. Over a bowl of matzo ball soup, the bodacious Strauss exuded: “Marvin, Jimmy Carter will never get the presidential nomination. You and I and five or six other governors will decide who the presidential candidate will be.”

But after Carter won an early round of primaries, Strauss attempted to establish a Carter blockade in New York, which held its primary on April 6, and Maryland, whose primary took place on May 18. Carter finished third in New York, Mandel delivered Maryland for Strauss, with Brown’s victory, but Carter simply won too many primaries (30) over a period of too many weeks to be denied the nomination. (Strauss never let bad judgment or personal enmities impede a resume upgrade or strategic advance. Strauss later accepted presidential appointments from Carter as U.S. Trade representative, ambassador to Moscow and peace negotiator to the Middle East.)

The May 1976 presidential primary election in Maryland was an object lesson for Carter and the beginning of a downhill slide as the final round of primaries headed to Western states. Mandel subscribed to rule number one in politics: Don’t get mad, get even. So in retaliation for Carter’s attempt to block Mandel from the chairmanship of the Democratic governors, Mandel put his well-lubricated Democratic machine to work full- force in support of Jerry Brown, handing Carter a humiliating defeat in Maryland.

But in one of those political ju-jitsus, Mandel did exactly what Carter would have done if the roles had been reversed. At the urging of Strauss, again, greasing his own future, Mandel offered a resolution, at a July caucus of Democratic governors in Hershey, Pa., urging that all Democratic governors bury their finely edged axes and support Carter for president. (I drafted the resolution.)

But Carter had the last toothy laugh. When Mandel’s docket came up for early parole from a federal prison sentence, the paperwork was approved at the regional level in Atlanta but was denied in Washington. Mandel believed to his dying day, on Aug. 30, 2015, at 95, that the denial was accomplished by the fine Machiavellian hand of then-President Jimmy Carter. The rest, as they say, is history.

The section on Jimmy Carter is adapted from my unpublished manuscript, “Shiksa: The Rise and Fall of Marvin Mandel.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution