Montgomery County Seeks to Reach Zero Emissions by 2035, But Advocates Say That’s Not Fast Enough

More than 80% of Montgomery County voters are concerned about global warming and 75% want to see their county council adopt a climate solution plan within the next six months, according to a recent poll by the Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

In 2017, the Montgomery County Council adopted a resolution that called for a “massive emergency global mobilization effort” and established a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2027 and becoming carbon-free by 2035.

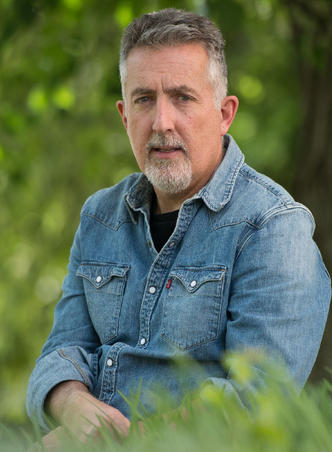

“I wanted a target that would make it extraordinarily difficult to say that the job is done until the job is actually done,” County Executive Marc B. Elrich (D) said during a virtual meeting Tuesday evening. Elrich sponsored the resolution as a member of the council.

But it took the county three years to publish a 130-page draft climate action plan, which Elrich unveiled Monday. Advocates contend that the county has not committed to any major legislation in the last three years to help achieve its reduction goals, nor does the draft proposal include any concrete legislative plan.

Since 2017, the county has launched initiatives to help reach its reduction goals, such as the Montgomery Energy Connection program, which provides information on the benefits of energy efficiency and available government programs, as well as the FLASH Bus Rapid Transit, which is Maryland’s first bus rapid transit service.

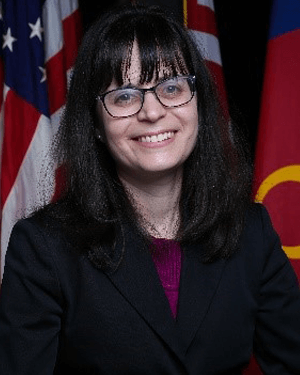

Mike Tidwell, director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

The county should have been setting more stringent energy efficiency standards to reach its reduction goals, such as banning new gas hookups to buildings by 2022, Mike Tidwell, the director of Chesapeake Climate Action Network, said. “We have to commit so that we are not just saying it’s an emergency but we are acting like it’s an emergency.”

The draft plan, created by more than 200 volunteers and county employees and consultants, is currently open for public comment until the end of February and will be finalized in the spring of 2021.

But advocates say this pace is too slow and point to the fact that 75% of Montgomery County voters said they support the council adopting a climate solution plan within the next six months, including 47% of whom “strongly support” such action, according to the poll.

“There is a disconnect between the county executive’s stated level of urgency and the specific legislative leadership that he should be providing right now,” Tidwell said.

Tidwell pointed to the fact that the Ann Arbor City Council in Michigan declared a climate emergency in November 2019 and by March 2020, issued a $1 billion plan with specific budget requests and deadlines for action and began implementing them in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Montgomery’s population is about 10 times greater than Ann Arbor’s.)

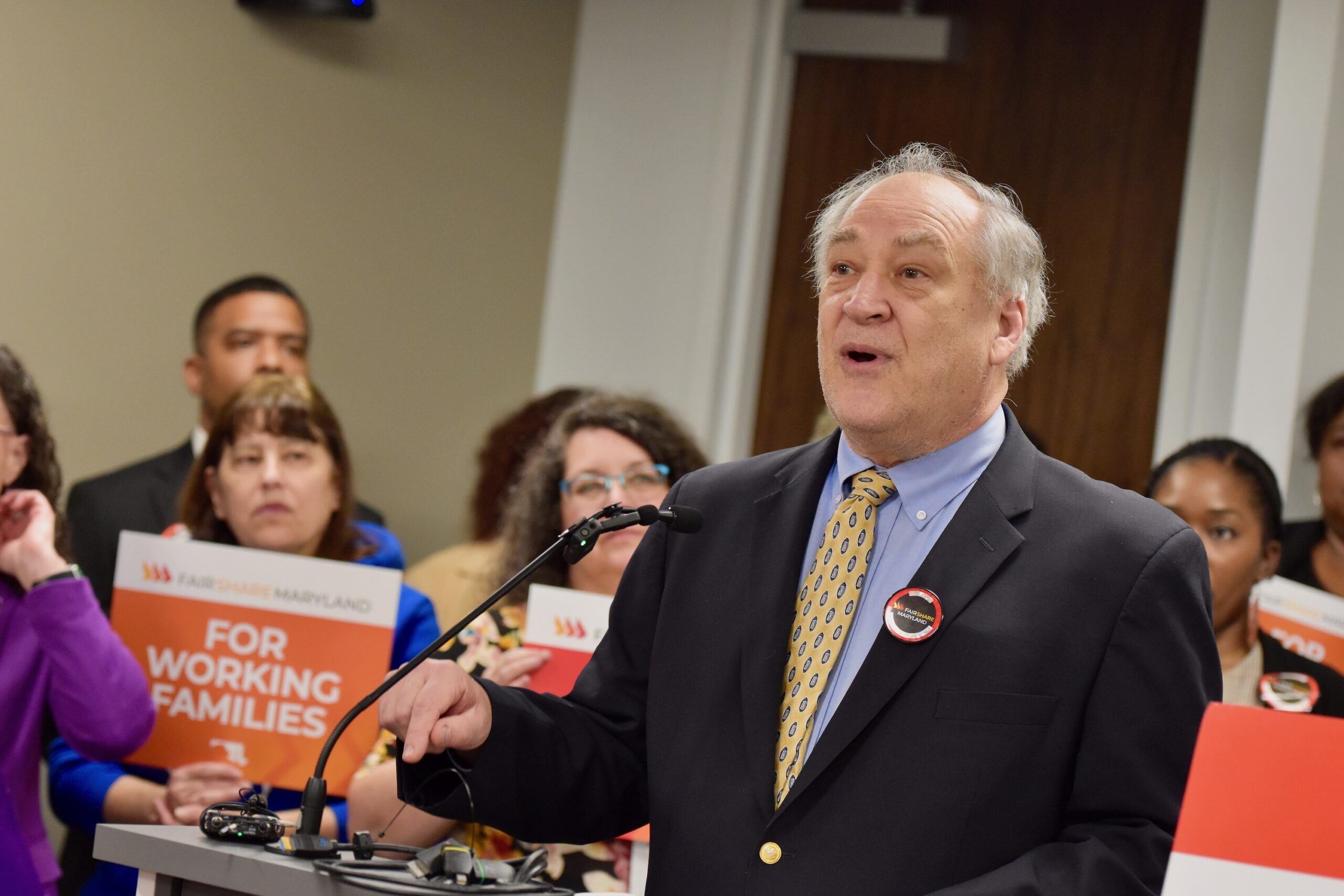

It took three years for the county to write a draft climate action plan because officials needed time to receive funding to hire outside technical consultants to do the modeling and analysis necessary to understand which climate actions the county needed to prioritize, said Adriana Hochberg, the assistant chief administrative officer for Montgomery County. The county spent $400,000 on consulting expertise to help prepare its climate proposal.

The draft plan includes 87 main climate actions that are split into five different greenhouse gas emission sources: clean energy supply, buildings, transportation, carbon sequestration and climate adaptation. The actions in each section are listed in order of highest greenhouse gas and climate reduction potential.

Adriana Hochberg

“This is not a menu of options, but helps us identify which [climate actions] are going to be the most impactful and the heaviest lifts in terms of securing funds,” Hochberg said. “These are multi-faceted issues that go just beyond greenhouse gas reduction; different actions have a variety of different co-benefits and some have real racial inequities that need to be grappled with.”

Half of the county’s emissions come from residential and commercial building energy use and 42% comes from community transportation, according to the report.

One of the county’s most prioritized action items is the Community Choice Energy program, a measure that Del. Lorig Charkoudian (D-Montgomery) introduced in the state legislature this year, but it did not pass. It will be introduced again next year and would allow the county government to become an electric supplier and purchase more renewable energy to green its electricity grid, Hochberg said.

However, the success of this program depends on what happens in Annapolis next session. Only if it is passed at the state level can the county council pass local legislation required to move the program forward, Hochberg said.

Another prioritized climate action item is to create an energy performance standard for existing commercial and multifamily buildings, which make up 30% of Montgomery County’s total housing units.

A building energy performance standard bill that would create standards for large commercial and multifamily buildings is currently being drafted and will be introduced early next year, Hochberg said. It would encourage building owners to make energy efficiency improvements while also giving them flexibility to determine how to make those upgrades. Over time, the standards would increase to ensure that buildings are working towards decarbonization.

The draft plan also includes recommendations to expand public transit service and pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure; to electrify buses; and to implement congestion pricing — or a fee for driving in areas that are used the most. Electrifying transit buses does not require legislation to move forward, Hochberg said.

It is the shared responsibility of the county council and the county executive to take the next steps and come up with legislative packages based on the recommended climate actions, Hochberg said.

Ensuring racial equity and addressing the disproportionate impact of climate change on underserved community is also a priority in Montgomery County’s climate action plan. More education on climate change and its impact, improved language accessibility and better public transit are among the key priorities in the report to ensure environmental justice. The draft also includes a map of county census tracks that have a high burden of energy and housing-related costs.

“The minority communities, communities of color…they are the places that are counted on to solve all the problems, to dump all the waste and handle all the toxics,” Elrich said. “We need to make sure that whatever plan we have is equitable and we make sure we don’t put things that are convenient without making sure that not only are they convenient but they don’t negatively impact the community.”

Both the county executive and environmental advocates acknowledge that this undertaking is ambitious, which is why the executive and council need to quickly digest the climate action plan and propose legislative responses immediately, Tidwell said.

“If we are having a real climate emergency and they’re moving at this pace, either there is not an emergency or it’s just political failure. It’s one or the other.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution