With reduced enrollment and revenue due to COVID-19 related capacity limits, plus higher costs for extra staff and cleaning supplies, child care providers in Maryland are asking state lawmakers for help.

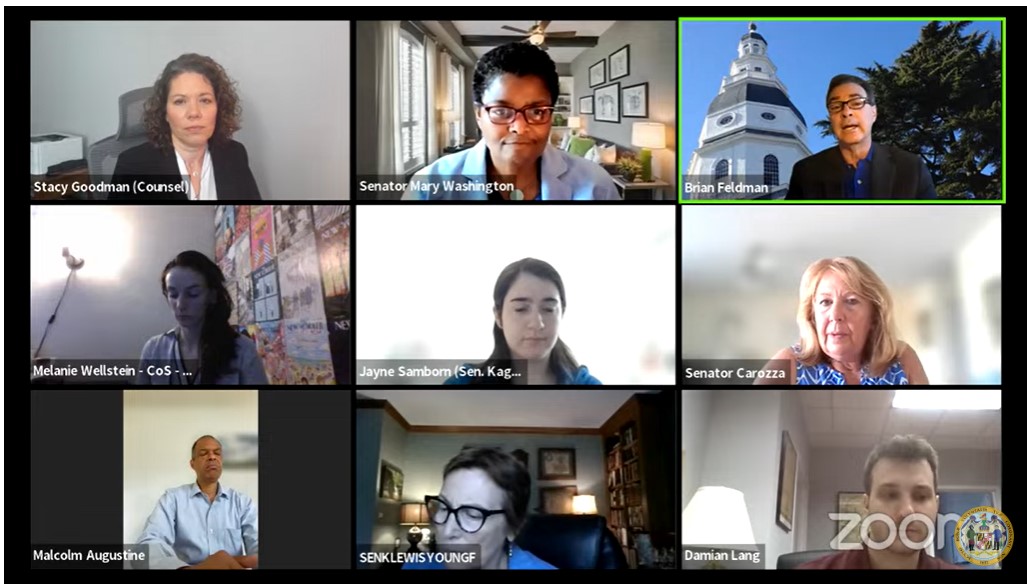

According to the Maryland Department of Education, 87% of child care centers have reopened since the pandemic hit in mid-March. But during a hearing of the Joint Committee on Children, Youth and Families Thursday morning, child care providers challenged that claim.

“Just because Maryland may state 87% of child care programs are open, it doesn’t mean that they have enough children or staff to sustain their businesses,” said Christina Peausch, executive director of Maryland State Childcare Association. Many only have half the number of children or fewer than they did in February, she said.

Peausch referenced a National Association for the Education of Young Children survey which found that 87% of child care providers said they expected to shut down permanently within a year if they lost 20% or more of their enrollment.

Not only have capacity restrictions been challenging, but Maryland’s child care specific COVID-19 protocols are not sustainable, child care providers argued. Every time a person has a confirmed case or exhibits a COVID-19-like illness, the child care center must close down. This means that even if one child has COVID-19 symptoms, all children in the classroom have to be sent home.

Carolina Reyes, who owns Arco Iris Bilingual Children’s Center, said she reported three cases of COVID-19-like symptoms and had to send all children home. But later all tests came back negative.

As winter approaches, there will be more cases of the flu, common colds, strep throat and bronchitis, which easily can be mistaken as COVID-19. It is not a sustainable for child care programs to have to close every time a child exhibits symptoms, child care providers said.

They also questioned the health metrics and science behind such strict guidelines for child care centers. Diana Heinz, the executive director of Children in the Shoe, noted that she can go into a restaurant without getting her temperature checked and sit next to people who aren’t wearing masks. But, at her child care center, she must do temperature checks and she “sends children home with runny noses.”

“Parents sit at home for five days, waiting for a child’s COVID-19 test to come back because they had a runny nose and a slight cough,” she said. “You do this in a classroom with 12 children, these are 11 healthy kids sitting at home with parents who can’t work…we’re closing for the common cold.”

“If we can’t keep the classrooms open, families don’t have the service they need, teachers don’t have the jobs they need and we don’t have the business,” she continued.

State lawmakers agreed that child care providers are essential to the state’s recovery from the pandemic and require more assistance as well as a seat at the discussion table. The joint committee’s draft recommendation included increasing the state’s investment in child care assistance, such as the Child Care Scholarship Program and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit.

Child care providers should be considered essential workers, Del. Susan W. Krebs (R-Carroll) said. “They need to be prioritized.”

However, counties also need to play their part in supporting child care systems, said Steven Hicks, assistant state superintendent for the Division of Early Childhood Development. The available state child care scholarship funding was budgeted to cover only school-aged children during the summer, school-aged children before and after school and children below school age for child care services during the school year. There is no additional state funding, Hicks said.

Laura Weeldreyer, executive director of Maryland Family Network, a non-profit group which advocates for children and families, referenced a recent Yale University study that surveyed 57,000 child care providers between May and June. That study concluded that those who worked in child care centers did not have a higher chance of contracting the virus.

Krebs said it is important to make sure state protocols for childcare centers are based on the most recent research, such as the Yale study.

Because child care programs are frequently closing while awaiting COVID-19 test results, more clients are leaving because they need consistent child care. Heinz said she has lost six clients because of this unpredictability. Providers who testified said some families have hired nannies or depended on another family members to provide child care.

Child care providers told state lawmakers that they need a revised protocol, including access to new rapid antigen testing and requiring a positive COVID-19 test before shutting down. They also asked for eased capacity restrictions and more state aid.

“We can really lift up and assert this industry as really key to Maryland getting back to work and asserting that they need to be part of the workforce and the business discussion that they are vital to that, and they’ve not been,” said Sen. Mary L. Washington (D-Baltimore City), the Senate chair of the committee. “This is an opportunity to assert that, not just for this crisis, but for the long-term.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution