Federal Rural Health Panel Offers Little Help for the Public on COVID-19

The pandemic is ripping through rural America, but the website for a federal advisory panel on rural health headed by former Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer is silent on COVID-19.

And Colyer, a Republican and a physician, continues to tout the use of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment despite warnings about its use. He also recently posted photos to his Twitter channel that show him standing close to two Missouri Republicans, Sen. Roy Blunt and Gov. Mike Parson — none of them wearing masks.

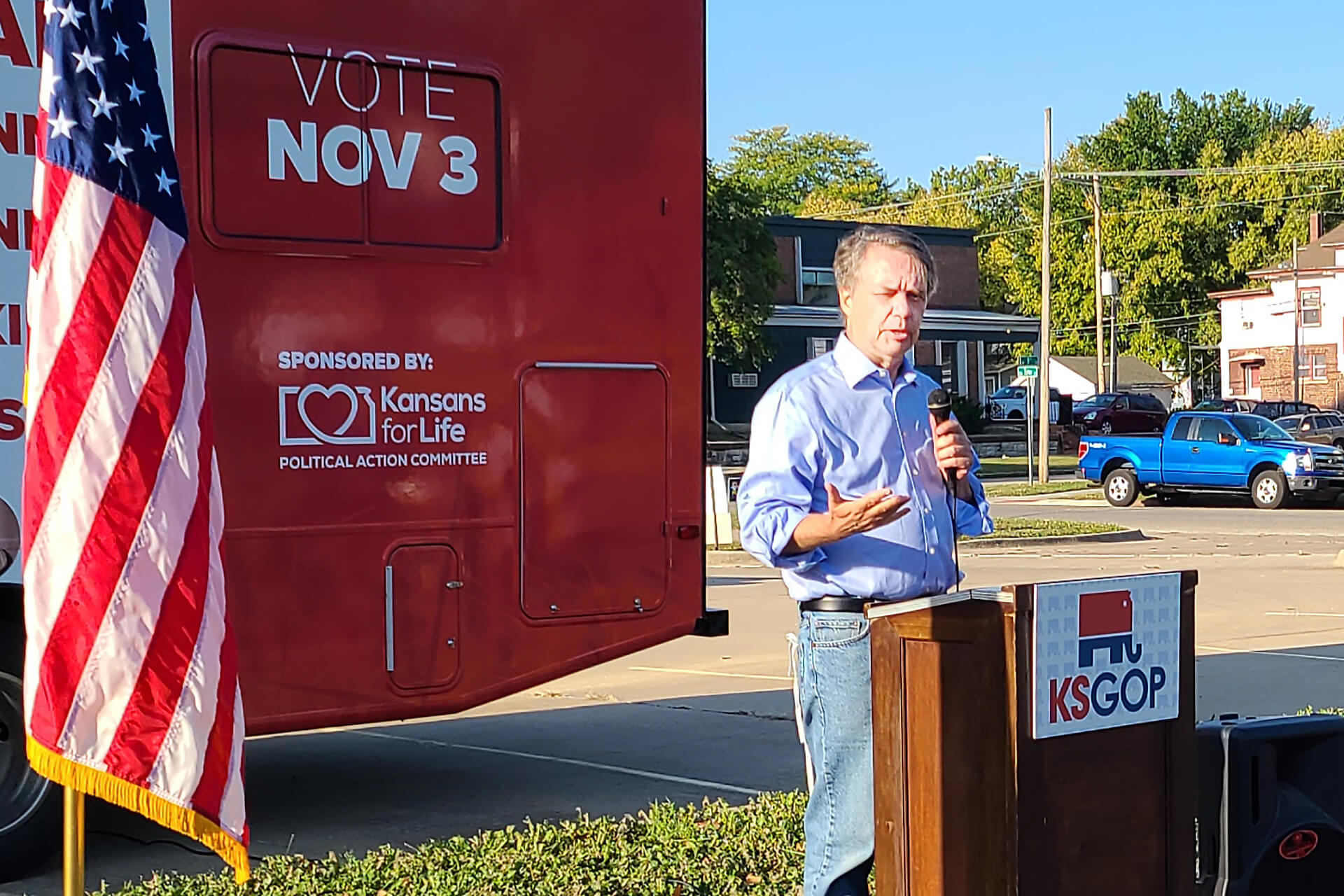

Colyer, campaigning in Topeka on a Kansas Republican bus tour earlier this month, says he’s been “very, very busy” leading the panel, despite its lack of public information about the health crisis.

Chartered in 1987, the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services is supposed to give advice to the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services about the provision and financing of health care in rural areas. Its members are from outside HHS, and it is apparently seen as important enough to the Trump administration to have survived a purge last year of advisory panels across the federal government.

Yet even though the virus is spreading quickly in rural areas, the committee hasn’t posted information on its website about the pandemic or its health effects in rural America. Public health experts say the government has failed to do enough overall in stemming the outbreak in the nation’s small towns and farm regions, as winter nears and temperatures plummet, sending people indoors and in close contact.

Colyer’s committee has regularly published policy briefs over the last decade. But other materials, such as letters to the administration and recommendations and reports to the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, have not been published to the site in years.

The committee website’s most recent letter to the administration dates to 2018; its latest recommendations are from 2014; and its most recent report to the secretary was released in 2011.

The committee held its second meeting of the year nearly three months ago but hasn’t posted information about it. And its most recent policy briefs — published in May — address pre-planned topics of maternal mortality and HIV prevention and treatment in rural America.

According to its website, the committee selects one or more topics to explore every year and produces a report with recommendations for the secretary. Committee members also send letters to the secretary and are authorized to produce white papers on other issues.

A charter document describes committee reports as optional and says the committee may meet up to three times a year, in person or on a webcast. Its annual budget is about $325,000, of which an estimated $189,000 goes to compensation and travel expenses for members and $137,000 goes to staff support.

The committee currently has 21 members, according to its website, but only 14 people, including Colyer, are listed as members — and the committee is in the process of adding members. The charter says the committee must have between 15 and 21 members, and the committee’s website says its size was expanded to 21 in 2002.

Colyer is the panel’s fifth chair. He was appointed in February, about a year after his gubernatorial stint ended.

He has touted hydroxychloroquine throughout the pandemic despite warnings about its use for COVID-19.

In June, the Food and Drug Administration revoked emergency use authorization for the anti-malarial drug and later cited safety concerns including serious heart rhythm problems, blood and lymph system disorders, kidney injuries and liver problems and failure.

In addition to hydroxychloroquine, Colyer has touted other therapies like convalescent plasma, which President Trump falsely claimed reduces mortality rates by 35%, according to FactCheck.org. The FDA has issued an emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma but hasn’t approved any drugs or therapies to prevent or treat COVID-19.

Colyer did not respond to requests for comment, though he cited his work on the committee on the GOP bus tour. “We had our first meeting at this obscure place — I’m sure you’ve never heard of it — called the CDC,” he told the audience, referring to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “And from that meeting onward, we’ve been very, very busy.”

Kari Bruffett, a committee member who serves as vice president for policy at the Kansas Health Institute, said in an interview that the committee has remained active in recent months.

The pandemic has disrupted some activities, such as in-person meetings and site visits, she said. But the committee met virtually in July to discuss its mission, vision and values and talked about producing a report about key issues facing rural Americans during the pandemic, she said.

Committee staff have since solicited feedback on those issues from committee members and are compiling information, she said. “I know that they’re working on that document now.”

A federal official, speaking on background, confirmed that committee staff are working on the paper and hope to publish “strategic visioning” materials from July’s meeting as soon as next week.

The official also said the committee is planning a virtual meeting this spring but that the dates have not been set yet.

Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association in Washington, D.C., said informal conversations about the pandemic in rural America are also taking place. He added that he has urged Colyer in recent weeks to take a “proactive leadership approach” in response to current events. Historically, the committee has set its agenda months in advance, leaving little opportunity to provide timely reports on pressing issues, he said.

Morgan added that he wished the federal government across the board placed a higher priority on updating government websites and keeping them current.

Rural hotspots

Coronavirus emergency funding enacted earlier this year has supported rural health during the pandemic, such as through temporary waivers on restrictions to telehealth and $10 billion in funding for rural health providers, of which $382 million is slated for Kansas.

“We now have telehealth that actually works,” Colyer said last week, noting that he was providing telehealth care from the campaign bus. “It was more convenient for my patients because they didn’t have to drive 150 miles each way to see me,” he said.

The Department of Health and Human Services, meanwhile, unveiled a “rural action plan” last month that details administrative and regulatory actions and new research programs and initiatives in rural areas. It notes that HHS will charge Colyer’s advisory committee to identify challenges in rural areas and recommend solutions — essentially its current responsibility.

Bruffett, meanwhile, emphasized the need to support the public health workforce and extend waivers on telehealth restrictions. “We don’t want to lose that ground,” she said.

The federal government needs to go much further to support the health of rural Americans, especially as chilly weather approaches, said Carri Henning-Smith, a public health professor at the University of Minnesota. Many rural health facilities need financial relief to stay in business, she said, and rural Americans need more access to affordable, high-speed internet service and electronic devices to access telehealth care.

But coronavirus relief efforts have stalled in a standoff involving the House, Senate and White House, which Morgan said means many rural health care facilities are going without the support they need to avoid closure and testing and tracing programs will go underfunded.

At the same time, millions of Americans could lose access to health care coverage or face higher premiums if the U.S. Supreme Court overturns part or all of the Affordable Care Act. It will hear a case challenging the law’s constitutionality next month.

“I worry a lot about what that would mean for rural health,” Henning-Smith said.

Morgan agreed, saying a reversal would be a “huge problem for rural America.”

Colyer has in the past called for the law to be overturned, saying it undermines the quality of care and damages the state budget. Kansas has rejected its option to expand eligibility for Medicaid, the government insurance program for the poor.

The issue has not come up in Colyer’s committee, Bruffett said.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution