As Courts Reopen, Public Defenders Fear for Themselves and Their Clients

Cynthia Christiani is a public defender and has served at Baltimore City’s district courthouse on North Avenue for 15 years. She said her office in the winding, windowless basement has seen minimal, if any, updates.

“I’ve never seen any updates to anything,” she told Maryland Matters in the courthouse hall last Friday.

Christiani called the building “frightening in general,” noting issues with the ventilation, flooding and a sewage problem a decade ago that left her without an office for weeks.

But as courts enter into their final stage of reopening as the pandemic continues to rage on, the fear becomes more tangible.

All of Maryland’s courts became fully operational Monday for the first time since Maryland Court of Appeals Chief Judge Mary Ellen Barbera ordered them closed in March, leaving Christiani and her fellow public defenders in a state of freefall.

“After declaring an emergency back in March and shutting down, the Maryland Judiciary issued a reopening plan in June,” said Charles County Public Defender Henry Druschel at a virtual forum held last week. “They named October 5 as the date on which full operations would resume. But as June and July and August passed, the Judiciary gave almost no guidance to stakeholders ― attorneys, litigants, court workers ― about what that reopening would look like and how it would be kept safe. And it’s only been in the last few weeks of September that those plans have started to take shape.”

The Maryland Judiciary entered into the final phase of its reopening plan Monday, allowing all of the state’s courts to return to full operation and for jury trials to commence. Barbera officially suspended the convention of all juries at the beginning of April. Criminal and civil jury trials have been postponed since March 16.

Under the final stage of reopening, anyone, including jurors, attempting to enter a courthouse must be masked, socially distanced and will be subjected to COVID-19 screening questions and temperature checks.

Refusal to comply with CDC guidelines or problems during the screening process will result in denied entry. If a prospective juror or a member of their household has tested positive for COVID-19 within two weeks of their report date, they are asked to reach out to their local jury office.

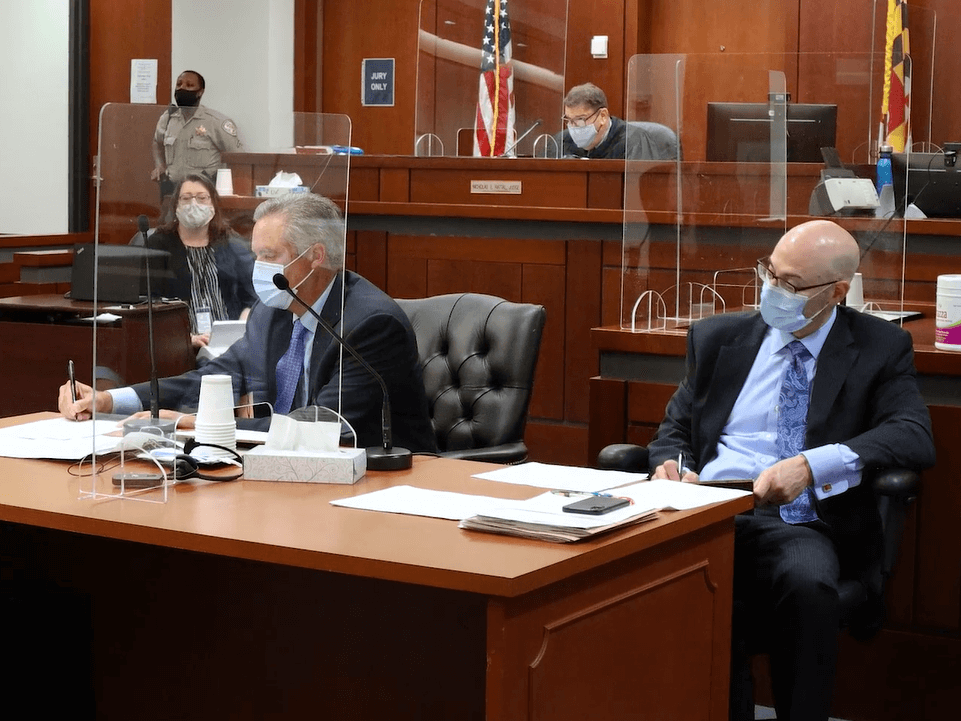

Barbera said in a statement that, out of caution, courtrooms have been fitted with plexiglass shields and staggered seating.

Jury trials require the assembly of large groups of citizens in order to allow the selection of an impartial jury. Doing this responsibly, while safeguarding due process, is a complex challenge that the leaders of the circuit courts have worked hard to meet,” she said. “Those called for jury service can be assured that we will continue to safeguard, as much as we reasonably can, the health of the public, including jurors, Judiciary personnel, and justice partners.”

Christiani, who typically practices in district court, follows her jury trials to the city’s circuit court. She said she’s already been told that misdemeanor jury trials won’t be held until 2021. Some of her clients facing misdemeanor charges have been in jail since 2019.

Labor representatives decry the decision to resume operations, calling the conditions “dangerous.”

In a letter to Barbera, the Maryland Defenders Union, a chartered AFSCME local, wrote that on Sept. 22 the Judiciary announced reopening plans but neglected to provide them to stakeholders.

Druschel said that the plans were made on a “courthouse-by-courthouse basis.”

“Courthouses across Maryland have remained open during the pandemic without proper sanitization, ventilation, and social distancing policies” the letter to Barbera reads.

The union questions the Judiciary’s plan to reopen, stating that it only serves to “provide cover for disparate, inconsistent, and dangerous local interpretations of what a ‘safe’ courthouse truly is.”

Ahead of Monday’s reopening, the Maryland Defenders Union, backed by leaders from other AFSCME Council 3 chartered locals and the Maryland NAACP Statewide Conference, asked Barbera to:

- Mandate independent professional hazard assessments for each courthouse;

- Instruct each jurisdiction to concoct and publish COVID-19 safety plans following the completion of the hazard assessments;

- Order a “statewide scale-back” to the Judiciary’s first phase of its reopening plan if Maryland’s COVID-19 positivity rate goes above 5%;

- Collaborate with all involved parties on ways to relieve the growing backlog of cases;

- Prioritize hearing cases involving those who are currently incarcerated;

- Supply personal protective equipment to all parties and HEPA air purifiers to high-traffic areas in courthouses; and

- Make certain that all high-touch spaces are frequently cleaned and sanitized.

“Upholding your mission to provide ‘fair, efficient and effective justice for all’ is a goal that we all share, but it cannot be achieved in the time of COVID-19 without effective leadership and action,” the union wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic will, unfortunately, carry on for many months after October 5; we cannot allow our clients, colleagues, and loved ones to continue to be needlessly exposed to this deadly virus in the interim.”

Despite the letter, courts across the state opened to the public Monday as planned.

A revolving door

Wearing a green surgical face mask and shield, Christiani met her clients Friday outside of the courtroom, laying out game plans before the judge gaveled in.

She walked into the Baltimore City District Court on North Avenue that day with a full plate: 23 cases. The maximum number of cases allowed in the courtroom where she practiced that day is 30.

Christiani explained that beginning in October, the district court started to limit its cases to between five and ten per hour. Before, she said, courts were seeing “unlimited cases” in the morning and afternoon.

She told Maryland Matters that she’s unsure how long cases will be staggered as they are now, saying there’s “no communication” from members of the administration.

“Is that going to be the case for November? I don’t know,” she said. “Nothing has really been communicated … it doesn’t seem like the people actually practicing [law] have heard the reasoning behind the decision.”

Christiani explained that the lack of communication doesn’t stop at the new docket format. According to a new policy, she said, defendants held in pre-trial detention are required to be tested three-days prior to their court appearances. There was one day where nine of her 11 clients weren’t transported to the courthouse because they weren’t medically cleared, “which means not tested,” said Christiani.

Several of those non-transported clients were eligible for probation, but their cases were postponed for two weeks because they weren’t tested in time.<

“Inmates and detainees are tested prior to known court appearances,” Mark Vernarelli, a spokesman for the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, told Maryland Matters in an email. “If the test result is not returned prior to the date of the court procedure, the inmate/detainee does not go to court.”

Vernaelli noted that dates and times of court appearances for incarcerated individuals are scheduled by the Maryland Judiciary, not the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services.

At the North Avenue courthouse, members of the public entered one at a time, were given temperature checks through a plexiglass shield with a slot in it and asked three screening questions: Have you had COVID-19? Have you been tested for COVID-19? Have you been in contact with anyone who has tested positive for COVID-19?

Only ten people were allowed in the courtroom at a time, leaving many to sit in the lobby and wait until bailiffs or attorneys called their names.

Every other row in the courtroom was blocked off with blue tape and available benches were marked to stagger attendees. Masked plaintiffs and defendants slid in and out of the rows as if moving through a revolving door. Benches were not disinfected as people passed through.

The judge and his clerk sat behind plexiglass shields as Christiani churned through her cases quickly. Many of her clients were absent.

On the trial tables in the front of the courtroom sat two big containers of disinfectant wipes. The wipes don’t contain alcohol, said Christiani as she pulled a small bottle of hand sanitizer from a plastic bag.

Christiani told Maryland Matters that she knows a few public defenders who have become infected or had to quarantine and that there’s “a lot a lot of fear about it.”

Since the pandemic began, said Druschel, a bailiff from Calvert County and two correctional officers from the Baltimore Central Booking Facility have died of COVID-19 and the Baltimore Sun reported Monday that a Baltimore City Circuit Court judge tested positive right as courts entered into phase five.

Peter Dooley, a certified industrial hygienist, told union members at last week’s forum that COVID-19 is “largely transmitted through air,” and is passed from infected individuals through “any kind of exhalation,” including speaking, sneezing, shouting and coughing.

He said to be aware of “the three c’s”: closed or poorly ventilated areas, crowded spaces and close contact, including close-range conversations.

“There’s no one silver sword out there,” said Dooley, “it’s a combination of things. It’s people wearing masks, it’s people doing remote work where possible, trying to avoid people having to go into buildings.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to correct the date of a courthouse flood and to include additional information from the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution