As Eviction Hearings Resume, Undocumented Immigrants at Highest Risk of Losing Homes

This is the fifth in an occasional series on Langley Park, a largely immigrant community in Prince George’s County where difficult living conditions have been made worse by COVID-19 and the accompanying economic crisis.

Maryland courts have reopened, their dockets filled with failure-to-pay-rent cases, and that’s expected to lead to a spike in evictions — if not immediately, by year’s end, when a CDC eviction moratorium announced last week is lifted.

During the pandemic 274,000 Maryland households have lost income and are in danger of foreclosure or eviction according to estimates from Stout, a Chicago-based consulting group.

Nearly 40% are renters.

José Linares is one of them. We’re not using his real name for fear of retribution.

His story begins in January at the Coronado Apartments in Adelphi, when his roommate got laid off and split, leaving Linares responsible for the $1,565 monthly payment. That was more than he could afford on his salary as a security guard for office buildings in the densely populated area bordering Langley Park, where COVID-19 cases are the highest in the state.

“I am always helping people, opening doors and jump-starting cars, simple things,” he says. In late April Linares came down with a bad cough, headaches and dizziness, then tested positive for the coronavirus.

He missed a month of work.

“My dad got COVID from me, was hospitalized, and lost his job. My mother isn’t working and my sister’s job just covers her kids, that’s about it.”

Linares, 29, was seven when he came to the United States with his parents from El Salvador, where the family had fled poverty and civil war. He applied for legal status 10 years ago through his mother, a legal resident, but his case has been denied and is on appeal.

No CARES Act

As an undocumented immigrant, Linares did not qualify to collect any rental assistance or unemployment benefits from the federal government under the CARES Act, which expired on July 25.

Yet, before January, he had never defaulted on rent and feels uneasy turning to his parents, who have their own money problems. He had helped them narrowly escape foreclosure when he moved to the Coronado two years back. “Their house is crowded with seven of them — my parents, my two little brothers, and 20-year-old sister and her two small kids,” he says.

When hired back to work after Memorial Day, Linares was deeper in debt. “Now I am in a bigger hole, which includes a monthly payment for a car I bought after my old one was stolen last summer,” he says. “Otherwise I couldn’t get to work.”

Warrant for eviction, few options

In the first week of August Linares received two notices: One, a Petition for Warrant of Restitution for $3,130, from the District Court of Maryland, a holdover from March when the courts closed, and another from the Coronado Apartments, a “Notice to Pay Rent or Quit” for $4,165.25 by Sept. 10, which was posted on his door with a neon pink sticker that read, “URGENT NOTICE” in English and Spanish.

In such cases failure to attend a hearing would trigger a warrant like the one he received. But Linares says he never got a letter from the court with a hearing date and was surprised to a receive a warrant for eviction signed by a judge.

He calls the “Notice to Pay Rent or Quit” from Coronado management “intimidation.”

“I’ve tried to negotiate with the manager, but she won’t take partial payment. They just want all the money [to date],” he says — adding that he feels unfairly treated. He says his documented payment history from Coronado Apartments shows he had paid the sum addressed in the warrant, but is worried that the management company will still go ahead with eviction.

“They don’t do anything for the people who live there,” he says, noting the vagrancy, drinking and drug use he sees regularly on the property.

When he was a student at High Point High School in Beltsville, Linares joined the Student Government Association. He mentored younger students and volunteered to leaflet for Prince Georges Council members’ election bids. Recalling that experience led him to send his eviction notices to Deni Taveras, his District 2 councilwoman, a tireless advocate for her constituents in Langley Park and a section of Adelphi, many of whom are Hispanic and undocumented.

Taveras immediately answered his call.

“My sense is that people have discounted this community, and this is going to come to a head right now if we cannot find a way to assist these families from ending up in the streets,” she says. “We have got to do right by these families who are contributing to our county, our tax base, and are doing the best they can to make ends meet, just like everyone else.”

Taveras fears not only failure-to-pay-rent cases overwhelming the court system, but also unscrupulous landlords. “They are counting on the fact that they are catering to a population that is not only undocumented, but probably not very well educated and not very familiar with their rights and process of eviction and due process under the law,” she says.

Taveras directed Linares for emergency rental assistance to the Beltsville Adventist Community Center and to Community Legal Services of Prince George’s County, a non-profit that helps low-income residents with legal aid.

Prince George’s County typically schedules 150,000 landlord-tenant cases a year. “This year we know the need is going to outweigh our capabilities,” says Jessica Quincosa, Community Legal Services executive director. “We are trying to plan for this pandemic eviction to help as many clients as we can and collaborate among our partners.”

Linares is currently seeking advice from counsel and reviewing his legal options.

He could get a reprise from the court under the CDC moratorium on evictions, although he would have to get his case before a judge before his management company acts to evict him. And, according to an e-mail from Community Legal Services, “The order doesn’t state that it is retroactive, but this can be argued. [We won’t] have an answer until we have a hearing where we can raise the defense.”

Time is running out.

COVID defense

If Linares survives the eviction warrant, his worries are not over.

The management company can go back to court for the balance on his account. He would be served with notice for a hearing. If he doesn’t show up, or can’t prove that COVID-19 was instrumental in his failure to pay rent, a new eviction warrant would be issued. But like the CDC moratorium, Republican Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan’s COVID-19 defense executive order is temporary and would end when the governor lifts the State of Emergency.

Campaign for General Assembly emergency session

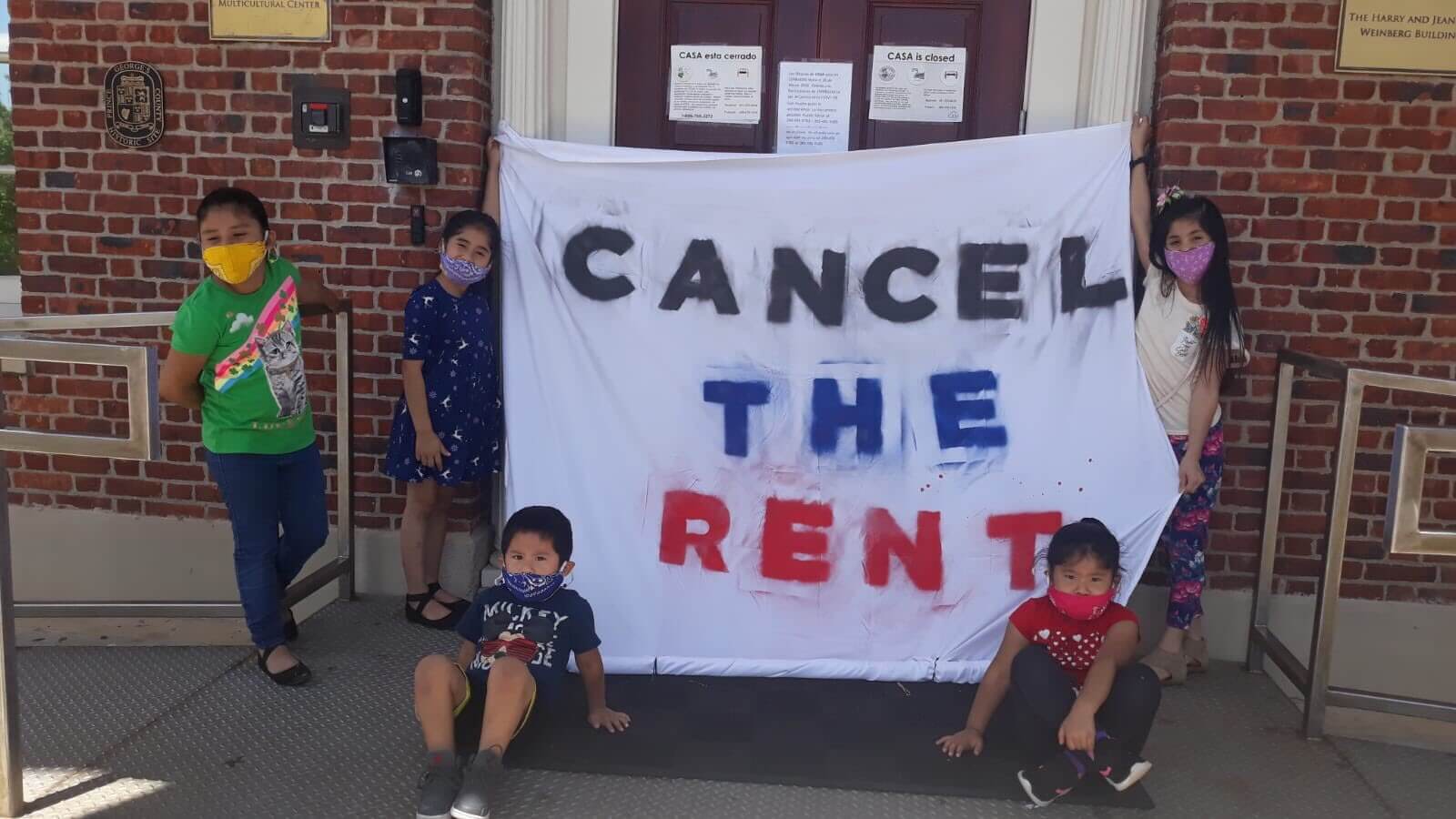

In August shortly before Maryland’s District courts began hearing tenant landlord cases, 80 advocacy groups, faith organizations, and municipalities launched a campaign calling on Maryland House Speaker Adrienne A. Jones (D-Baltimore County) and Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-Baltimore City) to convene a special session of the General Assembly to address emergency COVID protections for workers, renters and homeowners. Among them is CASA, the largest immigrant rights group in the mid-Atlantic.

“If there is an emergency that would require them to reconvene, it is now,” says Cathryn Paul a CASA policy analyst. “We’ve been pushing for at least a one-year moratorium on evictions after the Maryland State of Emergency, initiated by Governor Hogan, ends.”

Linares hopes to avoid the nightmare of coming home to find his possessions on the street, or worse, “being robbed of my things when I am at work,” he says. He is reticent about returning to his parents’ already overcrowded house, embarrassed that he has somehow failed them. He struggles to achieve the same freedoms as people born in this country.

“I love my community, and I want to help people, especially teens,” he says of his dreams for the future. “I’d like to be in law enforcement, but you need to be a citizen,” he adds.

Rosanne Skirble is a freelance writer who lives in Silver Spring.

Click here to read the first story in our Langley Park series, “Where the Pandemic Is Exacerbated by a Housing Crisis — and Vice-Versa.”

Click here to read the second story in our Langley Park series, “When ‘Focus on Survival’ Trumps Learning.”

Click here to read the third story in our series, “Langley Park Activist Leads With Heart and Soul.”

Click here to read the fourth story, “Langley Park Census Response Among Lowest in Md., Community May Miss Millions in Needed Funds.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution