Two political conventions took place in America – the tromp l’oeil on television and the social, economic and physical upheaval dragging the nation on the streets.

These combustible crosscurrents will juxtapose on the ballot in November to decide the next president and, more important, the durability of democracy.

Political conventions have taken place during wars, depressions, flu outbreaks, and other omens of apocalypse, but few, if any, have ever occurred against a backdrop of such enormous consequences for the lives and livelihoods of 330 million Americans, and then some.

Millions out of work, destructive hurricanes, wildfires in California, rebellious sports teams, the assault on the Postal Service, purposeful marches, the deadly contagion of a runaway virus, cops riddling black men with more perforations than a colander, senseless killings on the streets of our cities, civilian target practice on police — all grand opportunities for a despotic demagogue to wrap up the difference between the 40-percenters who will drink Kool Aid upon orders and the uncertain squeak of victory.

Frank A. DeFilippo

Voting is triage. Candidates know what votes they have, and what votes they don’t have. The persuadables are up for grabs. Trump has 40% that will stick with him like Krazy Glue. Biden is ahead in the polls, but as they tighten, he could crest at, say, even to 45%. That means about 5-10% of the vote is in play — a tight election by anybody’s measure. The electoral map is a whole different way of viewing the election.

Election year disruptions are a familiar cacophony. During the 1964 Republican National Convention in San Francisco, the air in the city of Cambridge, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, was heavy with the acrid bite of tear gas from more than two years of demonstrations and nightly protests to demand desegregation of local businesses. The unrest in Cambridge was propelled, in part, by the residual fervor from the 1963 march on Washington.

A contingent of the protest organizers segued to San Francisco to continue their demands during the GOP meeting, and when the conservative avatar, Barry Goldwater, was nominated as the Republican candidate for president, the Black members of the Maryland delegation walked off the convention floor in a symbolic protest.

Spiro T. Agnew, then Baltimore County executive and considered at the time moderate-to-liberal, was loudly denounced for his endorsement of Goldwater. But Baltimore Mayor Theodore R. McKeldin Jr., refused to support the GOP candidate and Democrats back home began to speculate that they might persuade McKeldin to support President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s reelection.

By the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, Democrats were openly talking about a McKeldin endorsement. It finally arrived, after McKeldin had talked it up for weeks. The Republican mayor endorsed the Democratic president at a rousing Democratic rally for Johnson at the Fifth Regiment Armory, in Downtown Baltimore. Johnson beat Goldwater by one of the most convincing defeats in history.

As a footnote to history, and as a gesture of appreciation, Johnson offered McKeldin the appointment as mayor of the District of Columbia, back when the job was a presidential patronage prerogative. McKeldin declined, telling the president that “the job should go to a Black man.” And it later did, to Walter Washington.

The campaign season of 1968 resembles that of 2020 more so than 1964. Cities such as Baltimore, Detroit and the District of Columbia were under siege and in flames. The times and the temper are perfect to reprise Richard M. Nixon’s law-and-order campaign as the pluperfect blueprint for President Trump to mimic, which he already has begun lip-synching.

That year, 1968, the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. culminated in the carnage of the “police riot” at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. President Johnson convinced Mayor Richard J. Daley to shut down his city by closing off all access as a way of keeping demonstrators out. They came anyway.

And the sight of burly Chicago police flailing away at defenseless teenage anti-war protesters was captured demonstrably in a Haskell Wexler film, “Medium Cool,” about a cinematographer being caught up in the middle of a demonstration he is trying to cover. An official investigation into the police over-reaction concluded that the action was a “police riot.”

Nixon, as every Maryland hobbyist knows, picked Agnew as his understudy and attack-dog to travel to under-populated parts of America to deliver the team’s crime-on-the-streets speech, with interchangeable parts to reflect the locale.

After one such noon-day delivery in Billings, Mont., a group of reporters wandered into a downtown department store to browse the local artifacts. A salesperson was asked if in such a tidy and quiet town in the middle of Big Sky country, there was a problem with crime on the streets, she replied:

“The only crime around here is those Indians sitting out there on the reservation, doing nothing but drinking and collecting government checks.” There you have it; the welfare gripe moved west.

By 1972, the Nixon-Agnew team was in full fury, and they had the perfect foil in Democratic Sen. George McGovern. Agnew, with his mouth full of Pat Buchanan’s vocabulary and his pockets stuffed with white envelopes, had developed a cult following of his own. Despite rumors, and the wish-list of key Nixon staffers, Nixon was unable to dump Agnew for fear of losing that chunk of support.

When McGovern & Co. arrived in Miami for the 1972 Democratic National Convention, the party was already divided and in disarray. McGovern and his campaign aides were among the few that understood the new nominating rules the McGovern Commission had designed following the Hubert H. Humphrey debacle in 1968. (Johnson refused to allow Humphrey to declare his opposition to the war in Vietnam.)

Humphrey, egged on by labor unions, attempted to reprise his earlier campaign, but was rejected by delegates who were bound by the new rules, which were being manipulated by McGovern aides. Miami was filled with love beads, long hair, anti-war protests and the sting of weed in the air.

At one pause, to the chagrin of conventioneers and the bafflement of the television audience, McGovern delayed his own convention to meet with protesters on the street.

McGovern’s acceptance speech – “come home, America” – urging an end to the war in Vietnam, was more of a lament than a prescription for his election. Another record defeat, even here in heavily Democratic Maryland, where Gov. Marvin Mandel’s key allies had endorsed Nixon and Mandel held out his support until the last minute.

That period in history briefly encapsulates, in many ways, the turmoil that America faces today. Some conditions are worse, some have improved, and others, such as the coronavirus, are new, but they are, nonetheless, ripe for the divide-and-conquer malevolence of a manic monocrat.

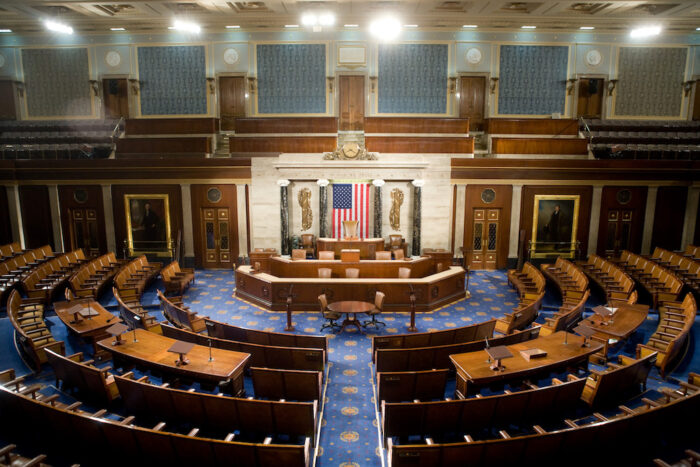

Often the convention on the streets is more compelling than the ones in the hall, or in this case, Zoom, and all sorts of remote locations, including Baltimore’s Fort McHenry — in violation of the prohibition on large gatherings, and, some argue, the Hatch Act, and later, the White House itself, where a mostly maskless crowd offered its ululations to Trump.

To his credit or detraction, which ever suits your whim, Trump has used the powers and the amenities of the presidency in ways never considered before, mainly because there’s nobody or no way to stop him.

Forget the words “norm,” “normal” and “normalcy,” a bastardized version of the word “normality” that was introduced to politics by Warren G. Harding with his 1920 slogan, “A return to normalcy.” “Normality” was probably a syllable to much for Harding to wrap his lips around.

The word — words — do not apply to Trump. He governs on the fly with whatever strikes his fancy, or appears on Fox News. The Democrats’ only recourse is to ask for hearings or investigations. The courts are slower than evolution.

Trump’s sister, Maryanne Trump Barry, a retired federal judge, secretly recorded by Mary Trump and whose transcripts were published in The Washington Post, was asked to name her brother’s major accomplishments: She replied, “Well, five bankruptcies.” Actually, there were six.

And someone should ask Secretary of State Mike Pompeo — and all of the other generals who staffed Trump’s White House — what it feels like for a West Point graduate to take orders from a draft dodger.

Impeachment didn’t work. The voters get their chance in November.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution