Testing ‘Remains a Struggle,’ State’s Public Health Chief Concedes

Despite efforts to protect nursing home residents from COVID-19 by limiting access to essential staff, “the virus is getting in,” the state’s deputy secretary for public health said on Tuesday.

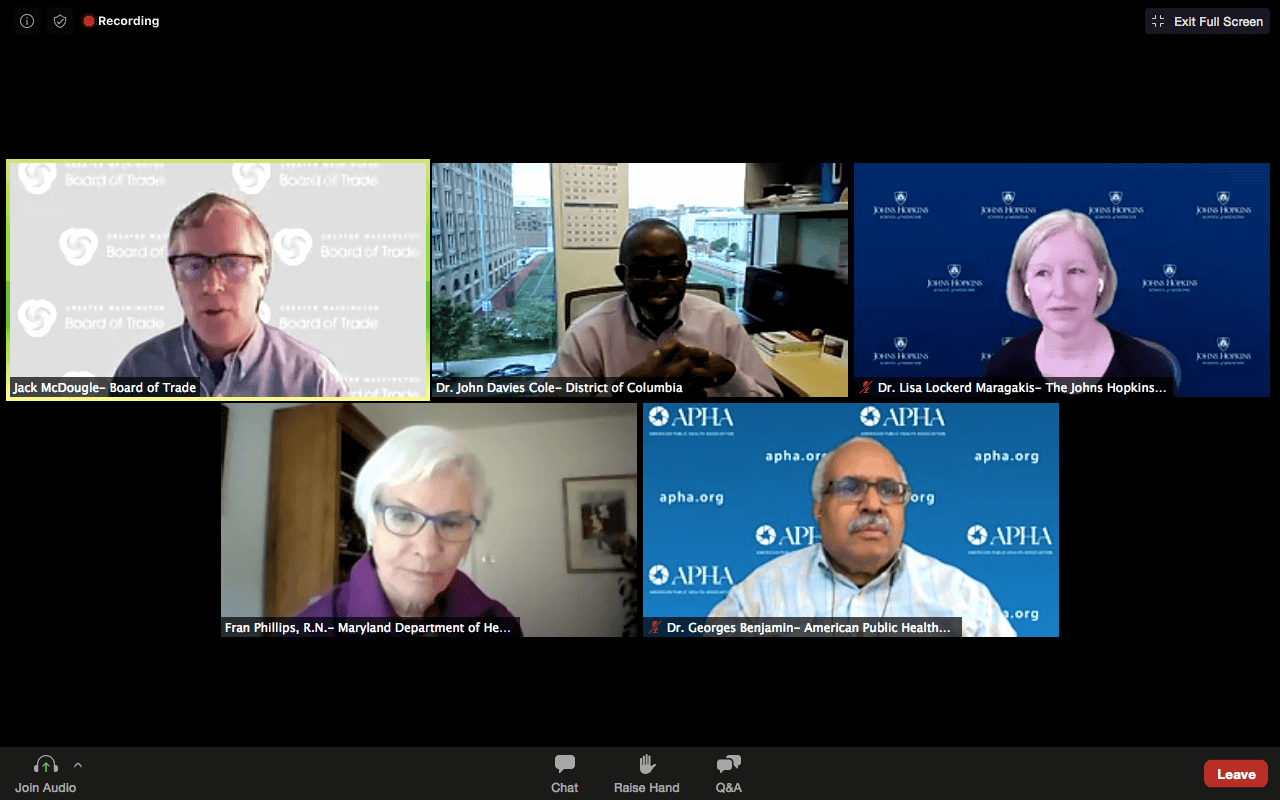

“That is because asymptomatic people, before they have any symptoms, are infectious, [they] are carriers,” Fran Phillips told a Greater Washington Board of Trade briefing on the novel coronavirus.

More than half of Maryland’s 2,217 reported COVID-19 deaths — 1,143, or 52% — come from the state’s congregate facilities, its nursing homes, assisted living facilities and group homes, according to the Department of Health.

The findings reinforce how easily the virus can be spread — and how important it is to protect the elderly and those with underlying health conditions, for whom COVID-19 is particularly dangerous.

Phillips said she recognizes that it has been a “tremendous hardship” for nursing home residents and their families to be cut off from one another.

Speaking alongside state health leaders from Washington, D.C., and Virginia, Phillips said testing of all residents and staff at all 227 of the Maryland’s nursing homes — about 70,000 people — is nearly complete.

The “universal testing” effort, done with help from National Guard personnel, has been essential “to understand who is infected, to either put residents in isolation or to have staff removed from the facility until they can come back safely.”

“We need to get that down to a baseline and have it stay there, after some serial testing, in order to make to sure it’s safe enough to re-open” facilities to family members, she added.

The next step is to bring vigorous testing to assisted living facilities and senior centers. That, Phillips said, is dependent on the need for “much more expanded testing capabilities,” an issue with which the state has continued to wrestle.

On April 20, Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) heralded the acquisition of 5,000 COVID-19 test kits from South Korea as “an exponential, game-changing step forward on our large-scale testing initiative.”

But five weeks later, testing remains “a struggle,” Phillips conceded. “Testing has been incredibly frustrating, I would say, for all of us.”

The kits Maryland procured lacked swabs and reagent, critical components that are in short supply the world over.

Completing the kits, to enable the 500,000 tests that Hogan touted in April, is moving forward slowly. State health department officials refused last week to make Phillips available for an interview to answer specific questions about the kits or how they will be deployed.

In a statement, the department said its public laboratory is producing up to 10,000 tubes of viral transport media per week “to overcome supply chain challenges.” Maryland is distributing more than 33,000 swabs to help local jurisdictions boost their testing capacity, a DOH spokesman said.

Last week the state expanded its drive-through testing capability.

“We were overwhelmed,” Phillips said. “We had thousands of people. We were able to test them. But this is not the typical way of doing business for lab tests.”

She said testing will become “more readily accessible” as pharmacies and other retailers gear up their programs.

“It’s not enough testing. Every day it’s a struggle to bring on more tests and to bring them out to the communities that need them,” Phillips said.

Contact tracing ramps up

Officials in the hard-hit D.C. area — suburban Maryland, the District of Columbia and Northern Virginia — have all said that expanded contact tracing is essential to reopening the region’s economy and allowing more social interaction safely.

Phillips said Maryland is using technology to develop “massive contact tracing on a mass call-center level.”

She said some of COVID-positive people “are readily-accessible, answer the phone, get the information and go into isolation without too much difficulty.”

“Other people are not going to be accessible on the phone. They may not speak English. They may not have a place to isolate. And those are the complicated cases where we turn to our local health department partners…”

Phillips stressed that the tracing program is confidential.

“Participating is really doing a public service,” she said. “It is really helping us suppress this virus. And this is what we’ve got to do until we’ve got widespread vaccinations on board, which you know is going to be some time.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution