Montgomery County Parents Fret About Privacy as Learning Moves Online

Montgomery County resident Joel Schwarz is a lawyer and father of four. His family has been learning to juggle newfound educational needs that come with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While his family adapts to distance learning, he worries about the safety of his and other kids as they spend more time in front of the computer. He isn’t alone.

Montgomery County Public Schools has adopted Zoom as one of its primary modes of educating students during the public health crisis. The platform, headquartered in San Jose, Calif., has blown up in the past few months, attracting over 200 million additional daily meeting participants between December 2019 and March 2020.

With unprecedented growth comes unforeseen problems.

“Zoombombings,” or breaking into meetings to harass attendees, became a major issue at the beginning of the public health crisis as government and business meetings struggled to move on to the platform. And while parents are concerned about the content that their students may become exposed to, they are also worried about the content that they may be unwittingly creating.

“There are a lot of community members who are concerned that Zoom has no privacy policy written specifically to protect students — and even more specifically, kids under 13,” said Lisa Cline.

Cline chairs the Montgomery County Parent-Teacher Association’s Safe Technology Subcommittee. She said that parents are afraid that recordings of their children in class are being stored in servers in China, potentially making it property of the Chinese government that “could be either hacked into and used for, you know, some malicious purpose or, or farmed out to someone who wants to know how that kid performed in fifth grade on a Zoom call.”

“It’s an exposure that a lot of parents are uncomfortable with, to put it simply,” Cline added.

According to the company’s blog, Zoom updated its policy in mid-April to ensure that data belonging to people who use the free app outside of China “will never be routed through China,” and that those who pay to use the app have the choice to opt-in or out of “specific data center regions,” including China.

But with over 160,000 kids in its public school system, Montgomery County was left with few options when it came to selecting a platform with enough bandwidth to deliver distance learning to its multitude of students.

“It’s hard to fight a bureaucracy when they spent a lot of money and there’s a lot invested and it’s also, obviously, a very unusual time,” said Schwarz, adding that, in acknowledging their lost battle, parents wanted to ensure that if students must Zoom that their personal information is protected.

Schwarz, Cline and seven other Montgomery County Public School parents recently penned a letter to Attorney General Brian E. Frosh (D) asking that the contracts between Maryland school districts and the educational technology vendors Zoom and Google be made publicly available; that student data be prohibited from being shared with third parties; and that both companies certify under oath that students’ personal information is purged once the pandemic is through.

“Let’s get these explicitly guaranteed to us so we sort of know that what our children are using is not going to have a long term impact in terms of privacy,” said Schwarz in a phone interview with Maryland Matters.

When asked, the Maryland Attorney General’s Office would neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation into Zoom, in accordance with policy.

In their letter to Frosh, parents wrote that they believe “some of the technologies deployed to assist in the effort to maintain Continuity of Learning while ‘social distancing’ pose significant privacy risks” to their children. Their main argument lies in the platform’s encryption services.

“End-to-end” encryption occurs when data and messages are protected from outside parties — including Zoom itself, according to Wired — as they are sent back and forth between meeting participants. The letter alleges that Zoom “misrepresented the encryption it uses.”

Zoom had been using the term “end-to-end” encryption without actually facilitating it. In a post from the company’s blog dated April 1, Zoom issued an apology for misleading its clients.

“Zoom has always strived to use encryption to protect content in as many scenarios as possible, and in that spirit, we used the term end-to-end encryption,” the post reads. “While we never intended to deceive any of our customers, we recognize that there is a discrepancy between the commonly accepted definition of end-to-end encryption and how we were using it.”

The company also clarified that unrecorded meetings where every party is using a Zoom app have encrypted audio, video, chats and screen sharing. It is reportedly not decrypted, or viewable, until it reaches the intended participant.

When Zoom attendees use other contact methods, like calling into meetings on a phone without the app, the company’s “encryption cannot be applied directly by that phone or device.”

A Zoom spokesperson told Maryland Matters that the company is working to improve its encryption capability, clarifying that “all video, audio and chat content is encrypted the entire time it is transiting the Zoom system.”

“Zoom does plan to offer end-to-end encryption to all paid accounts in the near future,” the spokesperson said. “On May 7, Zoom announced the acquisition of Keybase, whose exceptional team of security and encryption engineers will accelerate Zoom’s plan to build end-to-end encryption that can reach current Zoom scalability. Once completed, we believe Zoom will provide equivalent or better security than existing consumer end-to-end encrypted messaging platforms, but with the video quality and scale that has made Zoom the platform choice of over 300 million daily meeting participants, including those at some of the world’s largest enterprises.”

The letter to Frosh from Montgomery County parents alleges that Zoom’s encryption methods are “weak” and “vulnerable to cracking by adversaries.”

Attorneys general in other states have taken notice, notably New York Attorney General Letitia James (D).

According to a news release, James opened an investigation into Zoom’s privacy and security policies in late March, which led to an update in the company’s maintenance and enforcement approach earlier this month.

Virtual classrooms for K-12 learners are now able to be password-protected or students may wait to be admitted by their teachers to any Zoom session. Meeting administrators also have the ability to control student access to private chats and screen sharing, among other features.

Prior to the completion of James’ investigation, the company had implemented policies to limit data collection and sharing in primary and secondary education settings.

Per its K-12 Schools and Districts Privacy Policy, updated on April 9, before the company collects any student’s data, a representative of their school or school district — known as a “School Subscriber” — must contractually consent.

School Subscribers determine how and for what purpose student information is processed by Zoom. This information can include names, email addresses, school location, IP address and chat messages.

Chat messages and other shared content aren’t monitored by Zoom unless the School Subscriber asks to access it. The K-12 privacy policy states that that data is only collected to be provided to school officials unless otherwise directed.

Zoom’s K-12 policy states that students and their parents can request to have data deleted or decline to have more personal information collected, but those requests are fulfilled at the discretion of the School Subscriber.

Where are the contracts?

Some education systems have chosen to be particularly transparent when it comes to their relationship with the company and how long student data is held.

Under the state’s Student Data Transparency and Security Act, the Colorado Department of Education published terms of its contract with Zoom, noting that the company hangs onto their students’ personal information until 30-days after the department’s purchase order expires.

This is Zoom’s policy as outlined in its Family Education Rights and Privacy Act compliance guide.

Montgomery County Public Schools parents are asking for the same amount of transparency from their school system.

“In the midst of all this, parents in Montgomery County — and perhaps other parts of Maryland — are left in the dark about whether and how our children’s data is protected by Zoom,” their letter to Frosh reads.

Montgomery County Public School parent Ellen Zavian submitted a Maryland Public Information Act request to access the school system’s contract with Zoom.

In return, she received the company’s K-12 policy and terms of service — both of which are available directly on Zoom’s website. No traditional contract was delivered. She told a school official in an email that she wanted “an agreement that had an execution signature on it.”

“I wrote: ‘One cannot enter into [an] agreement, get over 150 licenses and not sign for such,’” she told Maryland Matters in a phone interview.

Zavian was told that the terms of service agreement from April 13 “is the current contract between MCPS and zoom.”

“There’s absolutely no way you can enter into an agreement with anyone without executing something for those licenses,” she said. “That means there has to be a purchase order — something.”

Additionally, Zavian was forwarded a notice sent out by Montgomery County Public Schools on April 6 titled “Important Information for Parents and Guardians Regarding Student Privacy and the Continuity of Learning.” This notice was intended to remind them of the district’s existing student privacy policies, information on what data is collected by Zoom, parental rights under the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act, and standards students and parents are expected to adhere to during the period of distance learning.

Maryland Matters reached out to Montgomery County Public Schools to ask what officials are doing to address parent concerns over student privacy and security online during the pandemic and was forwarded the same document.

Parents acknowledge that both the school system and Zoom are trying to make the best out of a sticky situation.

“I don’t think anybody is out to get Zoom,” said Cline. “Zoom was never intended to be an educational tool. A lot of people are using it because it’s a quick fix to a very sudden onset problem.”

“MCPS got caught in a trap, like most school districts did,” she said. “They had to do something really quickly and, and my hunch is that they have something better cooking for next fall if they have to continue this.”

At a minimum, Schwarz appreciates Zoom’s willingness to amend its policies.

“I like Zoom to the extent that they’re actually making changes and are responsive to people, which I think is a lot better to be that than the behemoth that doesn’t respond to anybody,” he said.

The “behemoth” in question is Google.

From a spigot to a firehose

The letter to Frosh also details privacy concerns surrounding students’ use of Google, who parents state has been “plagued by privacy problems for several years.”

“The roll-out of Google Chromebooks and the greatly increased reliance on Google Classroom have renewed our long-standing concerns regarding Google,” they wrote.

On March 26, the Montgomery County School system began handing out Google Chromebooks to ensure students in need had access to technology to continue learning during the pandemic.

Schwarz said that parents used to have some choice when it came to their children’s consumption of Google products in the classroom.

“But now Google has become the intensive tool of choice here because now every kid has a Chromebook at home, theoretically, at least in Montgomery County,” Schwarz said. “They’re using that exclusive[ly] for all their lessons, so you had a choice before now you really don’t because now you have to use the Chromebook if you want to get lessons.”

“So now you went from before where Google Chromebooks may be used part of the day, and it wasn’t mandatory, you had alternative options, you don’t have alternative options now,” he explained. “And you’re basically going from a spigot of information to this huge firehose of information feeding to Google.”

Schwarz said that while it’s possible to attempt to connect students to their classes using non-Google devices like iPads and laptops, Google products are configured to enable this type of learning, making it “much more onerous not to use a Chromebook.”

Even if families opt to use other products, students inevitably still end up feeding information into Google through its other programs, like Google Classroom.

The tech giant has been on the radar of Montgomery County parents for a while now.

Schwarz and a group of parents through the Montgomery County Parent Teachers Association instituted “Data Deletion Week” last September in an attempt to get the school system’s vendors to agree to delete unneeded student information and to certify that they had done so in writing.

Google did not.

Now that student information is being fed into the tech company through a “firehose,” Schwarz wants reassurance, which is why he and other parents have turned to Frosh for help.

“You know, and the longer this goes on without actually taking action and getting guarantees about their privacy, the longer we have to worry about the information being collated and created into large dossiers on our students, and who knows who it’s being shared with and where,” Schwarz asserted.

The letter to Frosh alleges that Google has not complied with inquiries about their children’s’ data for months and that the school district has not eased their concerns by “refusing to release its contract with Google to parents despite years of repeated requests.”

Montgomery County parents previously submitted a records request for this information, but, according to their letter, instead paid over $1,000 for “various Google forms printed off the website, purchase orders, and other general, non-responsive information.”

The parents say they have never seen any contract.

Marylanders aren’t the only ones concerned about Google’s potential exploitation of children’s data.

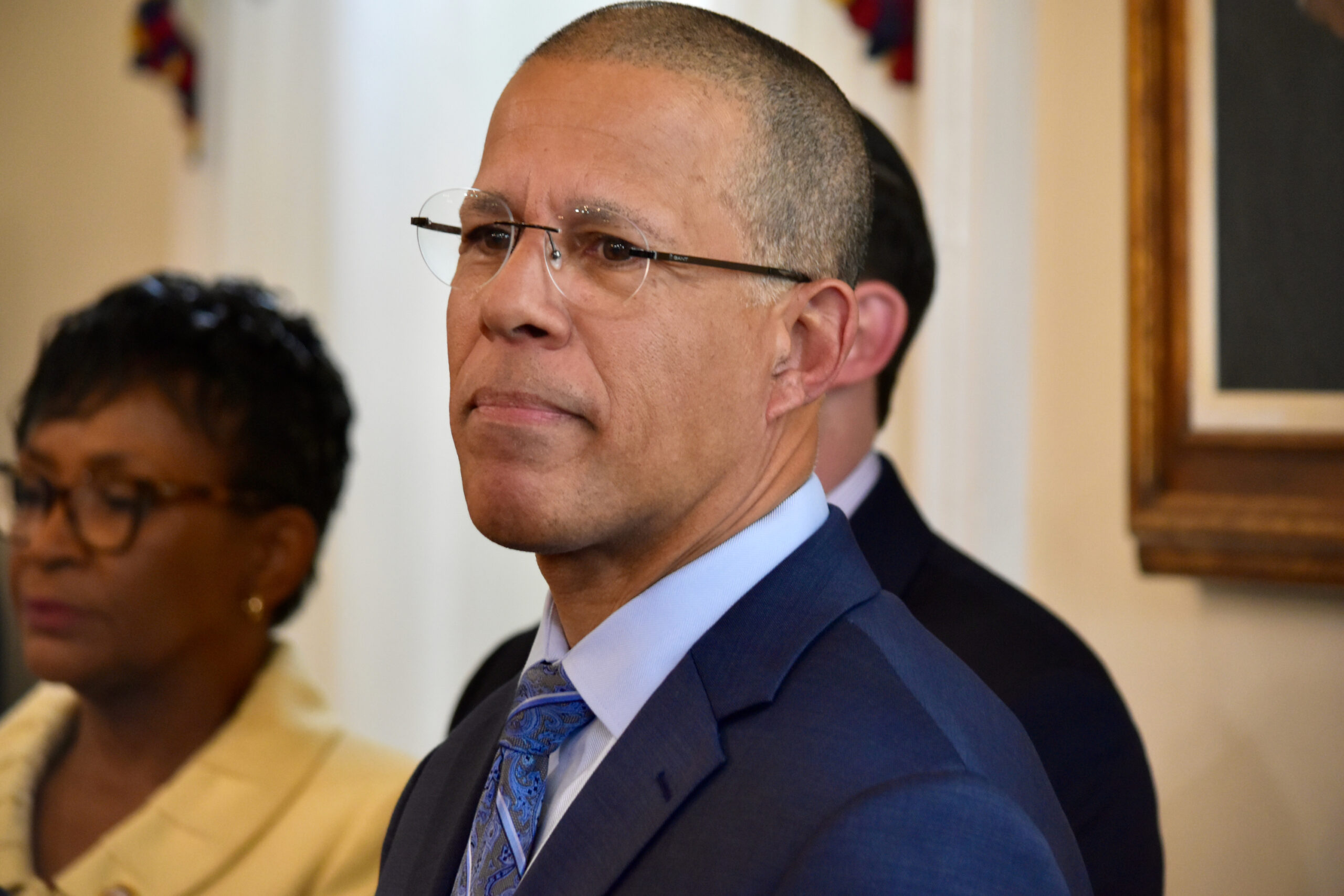

New Mexico Attorney General Hector Balderas (D) filed a lawsuit against Google in February, alleging that the tech company collects personal information, including the locations and voice recordings of students aged 13 and younger who use its products not out of choice, but necessity, and does so without their parents’ consent.

Balderas says this is in violation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, which dictates that children under the age of 13 cannot consent to privacy policies or terms of service agreements on websites, placing their parents in control of what information is collected about them.

Maryland Matters reached out to Google to ask about its policy surrounding the maintenance of student data, but has yet to receive a response.

“It is unfair and unjust to students and parents alike for the status quo to continue,” the Montgomery parents’ letter to Frosh concludes. “Maryland schools must not be permitted to continue utilizing these services in this new educational paradigm without full transparency as to the contracts binding Ed Tech vendors; without stronger, more public, more explicit binding requirements imposed upon the vendors to protect, segregate and then purge student’s personal information; and without an ability for families to formally opt out of use of these Ed Tech tools, while receiving realistic, legitimate alternatives (which do not currently exist in this remote, continuity of learning environment).”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution