Can Lessons From the Great Recession Help States Avoid Budget Disasters?

As they face massive budget shortfalls due to the COVID-19 pandemic, states are looking for federal money to help stave off the kind of drastic cuts they enacted during the last economic downturn.

State budget officers and economists generally agree that cuts to state spending worsened the Great Recession in the years following 2008. Layoffs, hiring freezes and furloughs of state employees had ripple effects throughout the economy.

As states again prepare for what they expect to be a sustained downturn, a comparable situation might play out without more federal help to close a collective budget gap of more than $500 billion.

“Any additional federal aid will lessen the need for cuts and lessen the impact that state spending cuts will have on the overall national economy,” said Brian Sigritz, director of State Fiscal Studies for the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO).

Federal recovery dollars made a dramatic difference to states dealing with the fallout from the Great Recession from 2008 to 2012. Getting aid to states quickly and flexibly was important to the recovery, said Tracy Gordon, a senior fellow with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center and a former economic adviser in the Obama White House.

The problem in the federal aid program was that it stopped too soon, Gordon and others say. Rather than tying continuing federal aid to economic factors like unemployment, Congress allowed the aid to expire before the economy had fully recovered.

“In the last recession, the [federal] money should have been continued longer, but political infighting prevented what many people hoped would be a second stimulus package,” said Wendy Patton, the senior project director for state fiscal issues at Policy Matters Ohio, a nonprofit research institute. “The federal aid ended too soon then, and we see ourselves headed into an even worse problem with the aid that’s been passed so far in Congress.”

To avoid such a fate this year, governors have asked Congress to extend benefits, like an increase to the federal cost-share for Medicaid expenses, until the national unemployment rate is below 5%.

Even with federal help during the Great Recession, states cut $291 billion in spending from fiscal 2008 to 2012, according to an analysis from Liz McNichol, a state budget expert and senior fellow at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. That accounted for 45% of all budget gap-closing measures, about double what federal aid made up and three times what tax increases did.

With many states seeking to avoid cuts to Medicaid — typically one of the larger expenses for state budgets — other programs could see even deeper cuts during a pandemic, NASBO President Marc Nicole said in a letter to Congress last month.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, groups representing states have also consistently asked for cash. The $2.2 trillion March relief package included $139 billion to reimburse state and local governments’ costs tied to addressing the virus itself and $30.5 billion for general education funding, but it still left a large gap for most states between their revenues and expenses.

The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that even when accounting for cash reserves states have been holding for an emergency — which were at an all-time high before the pandemic — they’ll be $510 billion short over the next three fiscal years.

There is bipartisan interest in providing more federal funding to states. Sens. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.) and Bill Cassidy (R-La.) are pushing a proposal that would provide “a minimum” of $500 billion to states, Menendez spokesman Steven Sandberg said.

But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has said he doesn’t want the federal treasury to “bail out” states and suggested they instead be allowed to declare bankruptcy.

As they did during the Great Recession, states will likely look to cut their biggest budget items, Sigritz said. K-12 schools, higher education, Medicaid and prisons are consistently the most expensive categories.

“I think you’re going to be seeing a number of states making cuts in those areas,” he said.

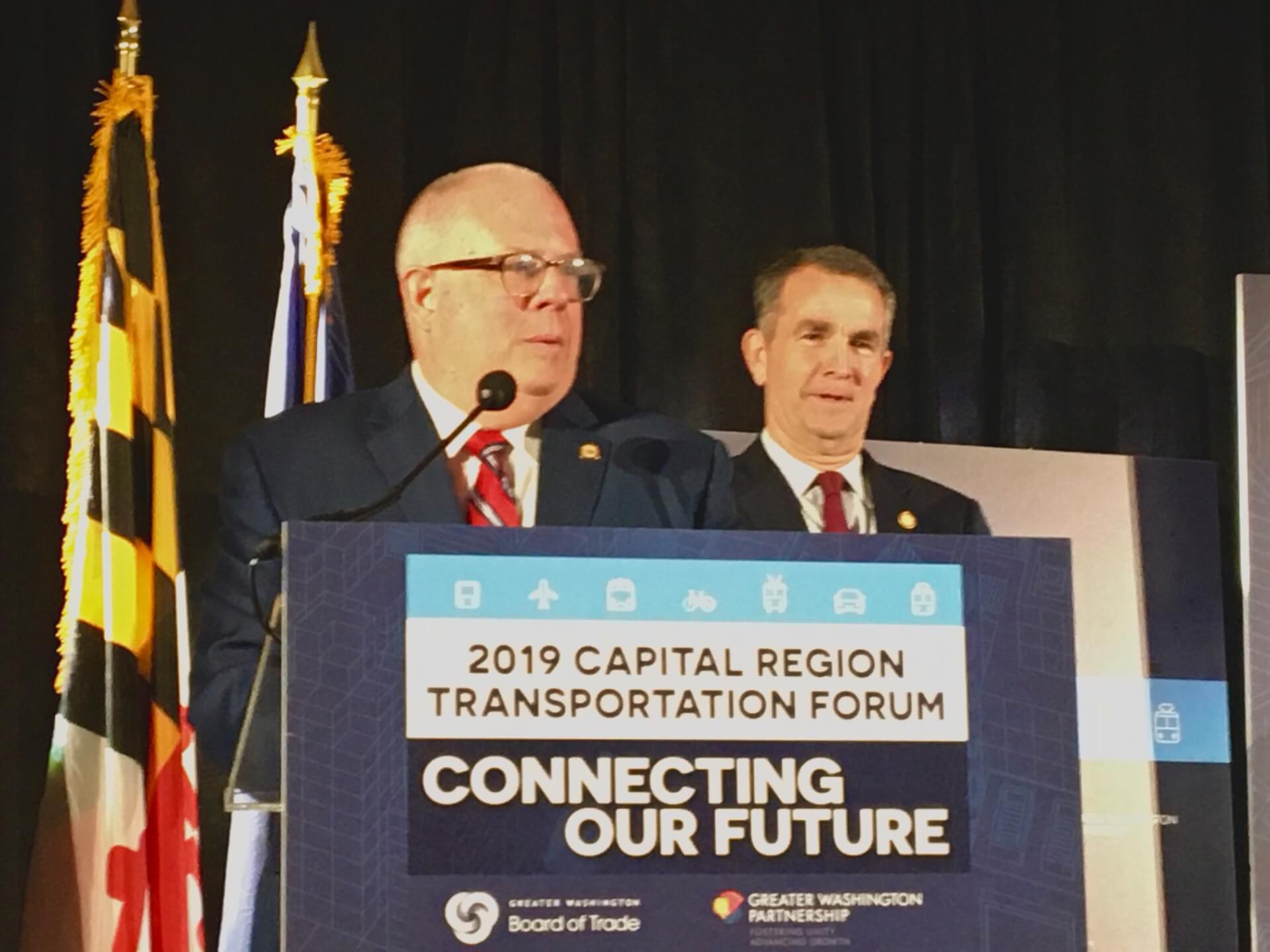

In Maryland, an early projection showed the state could face a $2.8 billion revenue shortfall when the 2020 fiscal years ends on June 30 — and Comptroller Peter V.R. Franchot (D) is expected to release another informal estimation on Thursday. Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) has already imposed a spending and hiring freeze for all but the most essential services.

It is also entirely possible that the state Board of Public Works will have to impose budget cuts before the General Assembly is next scheduled to meet in January 2021, just as it did in the late fall of 2008, weeks before the legislative session.

In other states, cuts have already begun.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, said last week he was cutting $775 million from the state’s two-year budget. Most of those cuts — $465 million — will be to education programs. Another $210 million will come out of the state’s Medicaid budget.

Democratic Virginia Gov. Ralph S. Northam proposed, and the legislature accepted, an amended two-year budget that virtually froze spending. Tuition assistance, teacher pay raises and other education programs were among the areas affected.

Projecting budgets is more difficult than usual now because the economic recovery depends largely on overcoming the related public health crisis, Virginia Finance Secretary Aubrey Layne said. The state has already cut discretionary spending, but a plan for “more significant action” will emerge later this year, he said.

With revenues down nearly $2 billion in the state and greater demand for expensive health services like contact tracing, general fund programs will almost certainly see cuts.

“Unless the federal stimulus funds become much greater in magnitude, or even some more flexibility, we’re going to have a reforecast of our revenues by the end of our fiscal year,” he said. “Obviously, it’s going to be a reduction of what we have in our budget … I know it’ll be down, I just don’t know how far down.”

Jacob Fischler is a national correspondent for States Newsroom.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution