UMD Flights Improve Air Quality, Greenhouse Gas Record

By Greta Easthom

As soon as the Cessna twin-piston airplane touches down on the tarmac at Easton Airport, a graduate student runs out with an extension cord to repower the ozone monitoring equipment on board.

The flight crew that just helped the University of Maryland research team land is slightly bemused at her urgency.

What they might not know is that her group — the Regional Atmospheric Measurement Modeling and Prediction Program or RAMMPP and comprised of 30 researchers and students — has helped the Maryland Department of the Environment improve regional air quality since 1999 by tracking how the ingredients for smog can originate from upwind states.

Due to Maryland’s geography and size, the state’s air quality is often affected by what is coming out of smokestacks upwind.

Traffic, development density and proximity to water — particularly the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic — also contribute to the state’s dirty air.

The costs can be staggering: hundreds of millions of dollars in health costs alone according to one regional study. And sometimes, not lowering one type of pollutant over another can cause environmental damage elsewhere in the atmosphere.

The state has failed updated national standards for ground ozone, and the RAMMPP team is studying exactly why, where and ways to fix it.

The scientists gather data to understand how things are happening now, and then use that to predict how things are likely to go in the future.

Tad Aburn, director of the Maryland Department of the Environment’s Air and Radiation Administration, said over the years, through RAMMPP’s modeling and research, the agency has been able to design programs to reduce ground-based ozone and the cocktail of chemicals that create it.

Despite the team’s efforts, Maryland has been in violation of the EPA standard for ground-based ozone, largely because while air quality is slowly improving, the federal agency has lowered the standards.

While having ozone high up in the atmosphere is good for human health because it forms a protective layer, ozone at lower levels — about 6 miles off the ground — is bad because it is one of the main ingredients for smog.

Measuring ozone in the lower levels through flights is important for determining how far away Maryland is from meeting national standards, what the main drivers of ozone pollution are and where they are located.

Mired in this murky air pollution problem are judicial battles that result when upwind states are pinpointed as sources of ozone for downwind states, such as Maryland, at certain monitored sites.

“If one surface site [exceeds standards], that’s the whole state” that has failed federal standards, said Tim Canty, research professor at the University of Maryland who has been working with RAMMPP for almost a decade.

“If one surface site [exceeds standards], that’s the whole state” that has failed federal standards, said Tim Canty, research professor at the University of Maryland who has been working with RAMMPP for almost a decade.

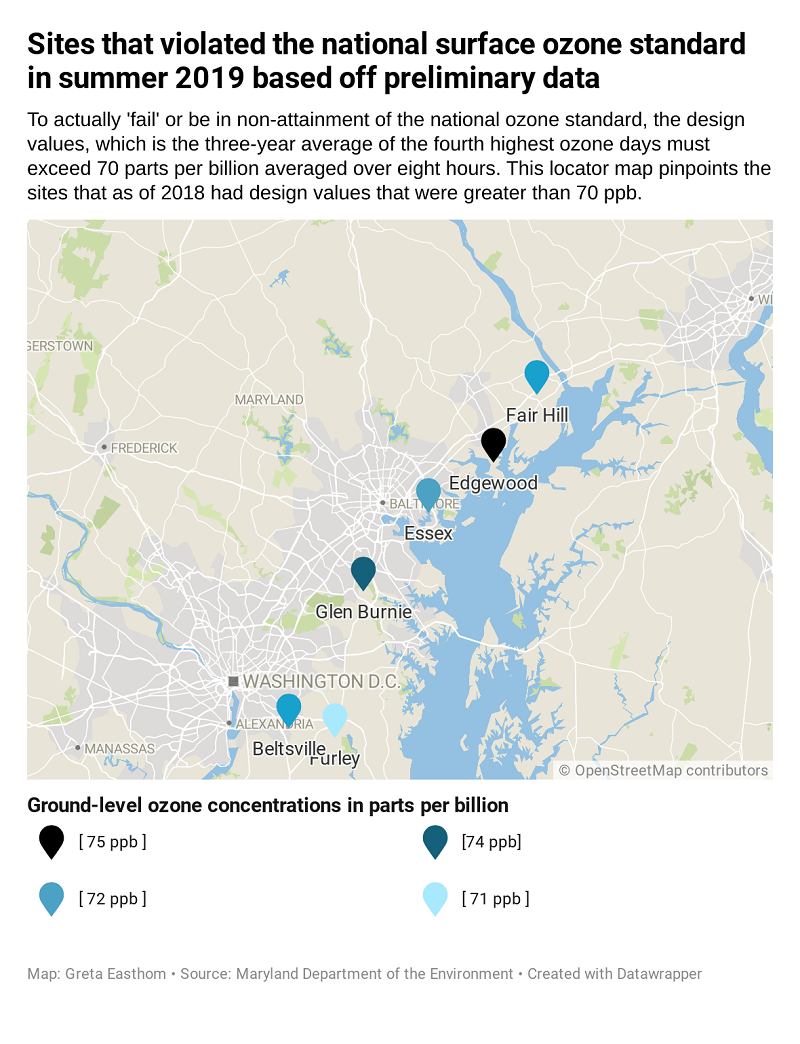

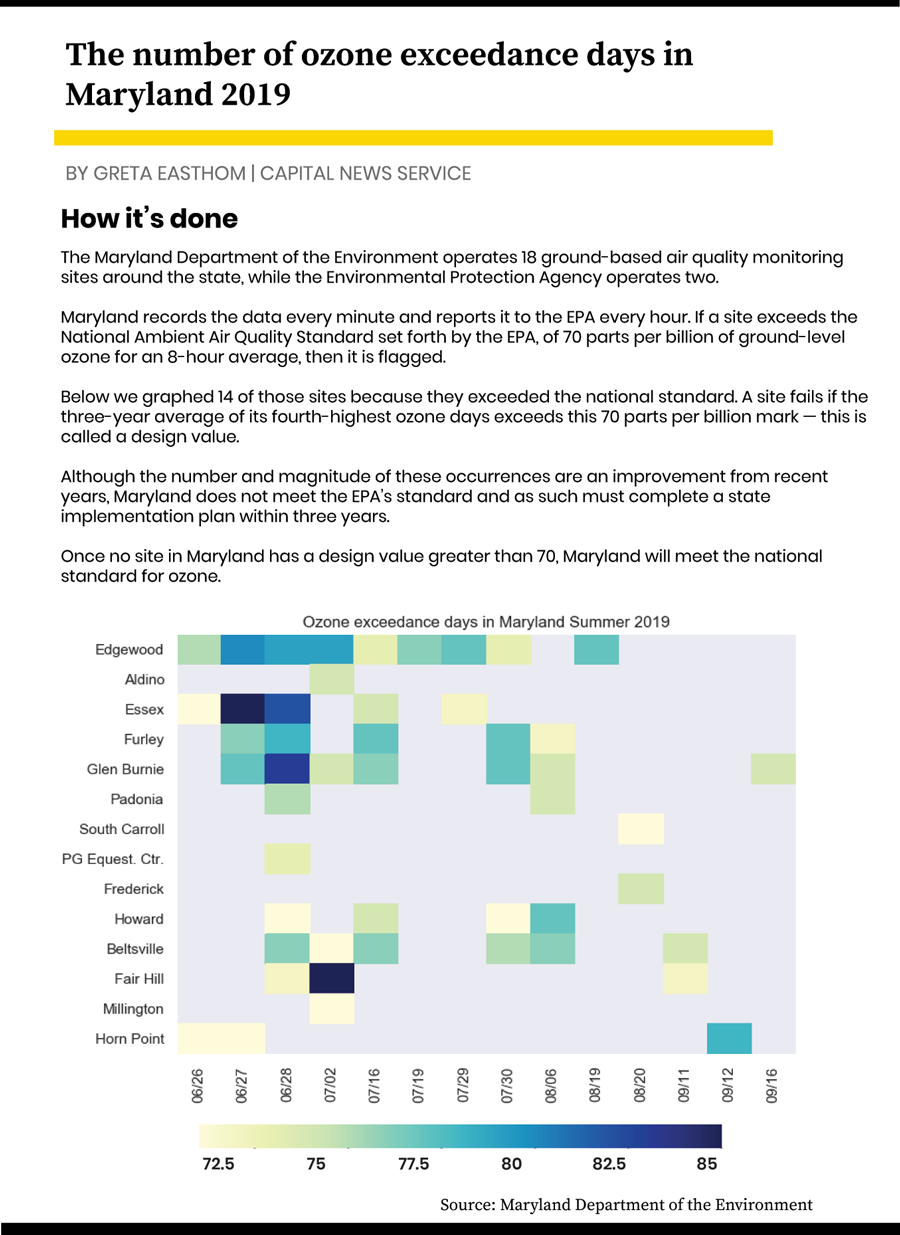

The EPA standard is based on a very specific average called the “design value” — the three-year average of the fourth-highest surface ozone readings in an eight-hour period for a given calendar date.

“And if that’s high[er than the standard], that’s pretty bad,” Canty said.

The reason why policy-makers average the fourth highest ozone day instead of the highest is because one day could just be an ozone outlier, and would skew the data too high.

The EPA standard for the design value of surface ozone is now 70 parts per billion for an eight-hour average; this decreased in 2015 from 75 ppb, and it could become even more strict.

If a site violates the standard over the three-year period, then Maryland must complete a state plan to compensate.

Six out of 20 monitored sites in Maryland have violated the standard this past summer. The preliminary design values for 2019 in Beltsville, Fair Hill and Essex are 72 ppb, Edgewood is at 75 ppb, Glen Burnie is 74 ppb, and Prince George’s Equestrian Center is at 71 ppb.

Ozone, while a big player, is not the only pollutant that is monitored. Sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide, lead, and particulate matter are all monitored and must meet national standards as well because they are six common pollutants under the Clean Air Act.

Particulate matter or aerosols are minuscule mixtures of solid and liquid droplets such as dust or soot, that can be easily accidentally inhaled.

Sulfur dioxide, which also comes from the combustion of fossil fuels, can form acid rain and particulate matter when it reacts with oxygen.

‘Not your typical science’

While the national standard for ozone, and the pollutants that create it, is uniform across the board, the different ways to measure and model these pollutants is not.

The EPA, the Maryland Department of the Environment and the University of Maryland all keep records of their current estimates of certain pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions from ground-based monitors, aircraft measurements and other recording equipment.

“It’s a challenge. It’s not your typical science,” Canty said. “Maryland Department of the Environment helps set up the strategies on the what-if, and then we run all the different scenarios [in the model].”

In other words, the researchers collect data on current conditions and use it to predict future ozone levels, playing around with different scenarios.

“We work as a consortium with other states in the Mid-Atlantic region … and then we modify from there based on our science,” Canty said.

Sometimes, how to use the data and which scenarios to plug into the models create disagreements among scientists and government officials. A location can pass or fail air quality standards based on which models or parameters are used.

One of those disagreements happened recently with sulfur dioxide. The EPA modeling process designated three sites in Anne Arundel and Baltimore counties as having the potential to fail, but Aburn said these sites have not been observed as failing and are not projected to do so based off Maryland’s modeling.

A state implementation plan was made anyway.

Sulfur dioxide can become a particulate, known as a sulfate, which can turn into acid rain.

“What’s important,” said Hao He, a professor at Maryland and RAMMPP researcher, “what will kill you, is … sulfate.”

Figuring out how to eliminate particulate matter like sulfates, “that’s the problem of the lifetime,” He told Capital News Service.

‘Air pollution is not our own problem’

NOx, the catch-all term for nitrogen oxides — such as nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide that can form ground-based ozone — comes from the combustion of fossil fuels and forest fires.

Once released from tailpipes or tall smokestacks, it produces surface ozone and can form acid rain.

The University of Maryland research showed that decreasing nitric oxides high in the air helped abate ozone levels on the ground, Aburn said.

The hot air masses rise from a couple-hundred feet high smokestack in Pennsylvania for instance, and a high pressure system can funnel these ozone-laden air masses in to Maryland.

The transport takes anywhere from one to a couple of days, He said.

“Air pollution is not [entirely] our own problem,” He said, “because Maryland is relatively small.”

The geography and heavy traffic of a densely populated and bustling Baltimore, along with other cities and towns near the Chesapeake Bay, can make them a hotbed for high levels of ground ozone, especially during the summer.

If NOx-rich, hot air rises, the air will circulate back over land as a bay breeze now thick with ozone-laden air.

If NOx-rich, hot air rises, the air will circulate back over land as a bay breeze now thick with ozone-laden air.

Edgewood, located northeast of Baltimore and along the Chesapeake Bay, has tipped 90 ppb as a design value in recent years due to its unique geography, squeezed between the city and the water.

Ground-based ozone also commonly tracks from southwest Washington, D.C., along the I-95 corridor, to northeast Baltimore, said Xinrong Ren, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Air Resources Laboratory and RAMMPP lead researcher.

This setup combined with “Baltimore emitting [pollutants] itself,” said Ren, created the perfect storm for Baltimore to have an ozone concentration of 120 parts per billion per second during a June aircraft observation.

Though this is different than the EPA standard, which is averaged over eight hours, it is still not a great reading.

There are other factors, according to University of Maryland graduate student Sarah Benish. “Generally air pollution is worse over water than land because it’s hotter, reaction rates are faster, [there is] less cloud coverage, [and] more direct solar radiation.”

“We’re trying to fly under certain conditions and there’s not a lot of legroom,” Benish said.

The Maryland Department of the Environment’s air quality forecasters will often pinpoint the high pressure, sunny days to the team. The stagnant, warm air that can form from during these types of weather conditions have in the past been a good indicator of bad air quality days.

Why the Maryland Department of the Environment keeps pushing for “more and more” in terms of NOx reductions is that “about 70% of Maryland’s [ground-level] ozone originates from [states that are upwind and their emissions],” said Aburn.

Despite this, for a while air quality was starting to improve in Maryland, as more NOx scrubbers were installed and run in Maryland’s own power plants.

Now, “it looks like air quality [could be] getting worse and we might not be in attainment of the old standard soon [75 ppb],” said Canty.

The reasons are unclear: “This is an area of ongoing research trying to figure out why that might be,” he said.

The researchers are trying to pinpoint whether this is a temporary anomaly.

In November 2016, Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh filed a petition under the Clean Air Act — known as the Good Neighbor Act — requesting the EPA to require certain power plants in Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia to run their NOx controls, which would effectively lower their NOx emissions.

In September 2017, Frosh sued the EPA for not responding to the petition by the required extended date of July 15, 2017.

The EPA denied the petition in October 2018, and Frosh is challenging the petition again in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, scheduled for January.

On Oct. 1, the D.C. Circuit Court struck down an EPA ruling that required upwind states to employ only partial reductions on factory emissions. It’s a bit of a Catch-22: The concern is that the federal rule may not lower pollution levels of downwind states enough for them to meet federal guidelines.

The EPA had until Oct. 29 to challenge this decision and would not tell Capital News Service whether they challenged it or not. Nothing had been filed on Westlaw as of Dec.4.

There are 36 power plants upwind in other states that could cut emissions of NOx with “scrubbers” and improve Maryland’s air quality, Canty said, but they are costly to run.

If a private power plant is meeting its NOx emission standards set forth for it by the state, it does not have to run its controls all the time.

If a state is contributing more than 1% of ozone to downwind states, they have to help make improvements on downwind air quality.

“We did a lot of modeling to show that if these power plants ran their scrubbers, it would allow Maryland to attain the [ozone] standard,” Canty said.

Researchers in Delaware found that “because of these power plants not running their scrubbers, it’s causing [Maryland, Northern Virginia, D.C. and Delaware] three quarters of a billion dollars in health costs,” Canty said.

Perhaps most troubling is that, “they can turn off the scrubbers when it’s hot outside,” said Russ Dickerson, another lead researcher for RAMMPP and professor for Maryland, in order to offset increased demand for electricity.

But this is when ozone production has the potential to be at its worst.

For power plants, there are monitors in the stack, said Dickerson, and those are “pretty accurate, but we can test those by flying the aircraft through the plume,” of upwind and downwind states.

“We fly a lot of Maryland, we’ve also flown in West Virginia, Virginia, New York — kinda the whole eastern side of things,” Benish said.

Taking flight:

When the researchers take flight, they take measurements called “whole air samples.”

“Think of an aluminum balloon that’s maybe this big,” said Benish, holding her hands as though around a large loaf of bread, holding about 3.2 liters, “and we fill them up for two minutes … and then send them to the Maryland Department of the Environment to be measured for hydrocarbons.”

“So I had to do those every two minutes for 20 minutes and I was getting super airsick,” she said.

Sarah Benish gets ready for a flight. It is her job to seal up the whole-air samplers, which are later sent to the Maryland Department of the Environment. Photo courtesy of Sarah Benish

Benish said it was hard to look down on all the boating, camping and hiking taking place at these sites, with the knowledge that bad air quality was affecting people’s health.

What to limit:

Air quality research can be tricky. Scientists must also determine whether decreasing certain chemicals — NOx or volatile organic compounds — will accelerate ground-level ozone production.

Volatile organic compounds are any mixture of carbon, such as carbon monoxide, and can be emitted from smokestacks and tailpipes of cars, too.

Twenty years ago, the general consensus in the air quality community was that volatile organic carbons were the main driver behind ozone production. RAMMPP’s research was crucial in determining that decreasing NOx was generally better for decreasing ground-level ozone.

“We all assumed organic driven,” said John Quinn, director of state affairs for Baltimore Gas and Electric. “We learned we had to reduce NOx a lot” [from Dickerson’s research].

“However, as emissions and air quality has improved, it’s getting harder to predict ozone exceedance days,” Canty said. “It used to just be warm temperatures … now you can have not as warm temperatures with an air quality exceedance event [or vice versa].”

Canty’s graduate student Allison Ring also found that volatile organic carbons might be getting overlooked as everything else gets cleaner.

Sometimes, in localized areas when the NOx is high and volatile organize compounds are at low levels, NOx scrubbers can exacerbate ground-level ozone, another problem for scientists the study, Canty said.

Cars are an even harder problem, Dickerson said.

Dickerson’s graduate student Dolly Hall has helped implement a monitoring site at Savage to detect emissions from motor vehicles.

“Transportation is hard to model and harder to legislate,” Canty said.

Canty said that different factors such as the rules on the efficiency of after-market catalytic converters and gasoline formulations are all parameters that are hard to specify in a transportation emissions model, especially with changing legislation.

Methane measurements:

While air quality is generally a problem the researchers focus on in the summer, carbon dioxide and methane emissions — contributors to climate change — are measured in the winter.

While there is crossover between the groups, this research goes under an initiative the scientists call FLAGG-MD, which stands for Fluxes of Atmospheric Greenhouse Gases in Maryland.

It is funded by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, with support from the Maryland Department of the Environment.

The team flies around the East Coast for this research as well, employing what they call “a box method,” to get an accurate measure of the amount of methane in a given area at a given time.

The Marcellus Shale — a geological feature that is the source of much of the region’s natural gas — and Baltimore — with the state’s largest methane-producing landfill, are two big methane concern areas, Dickerson said.

Maryland Department of the Environment and the EPA keep inventories, or records, of greenhouse gas emissions.

Baltimore’s inventory definitely needs to be improved and there are lots of uncertainties surrounding the Marcellus Shale leak rates.

A leak rate is a percentage of the amount of methane lost to the atmosphere when it is pumped out of the ground at natural gas and oil wells. Older pipes will leak gas when transporting it as well.

Aburn said the Maryland Department of the Environment is working with the research team to adjust their inventory numbers for methane so that their estimates for landfill emissions are more aligned with University of Maryland’s estimates.

Methane levels at Brown Station Landfill in Baltimore were measured at 10 times higher than the EPA standards and five times higher than state standards.

“There is a gross difference in [our records] of Brown Station Landfill,” said Ross Salawitch, “which is the largest source of methane in Maryland.”

However, Salawitch acknowledged that the Maryland Department of the Environment and RAMMPP employ very different modeling approaches as Maryland’s is more observationally driven.

Salawitch said the EPA and the Maryland Department of the Environment are underestimating leaks of all landfills by a factor of around two.

Furthermore, “it doesn’t take much walking around Baltimore and Washington to know there is aged infrastructure,” and with aged natural gas pipes, which distribute into homes and businesses, come leaks, Salawitch said.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas and has a great global warming potential on a 100-year time scale, but an even greater impact on a 20-year time scale. The impact is greater over a 20-year timescale because it is more concentrated.

Salawitch is hopeful that the state will soon implement a 20-year global warming potential in its evaluations but that doesn’t seem to be happening anytime soon.

An aerial picture of Baltimore from June 2018, taken during a RAMMPP research flight. Photo courtesy of Sarah Benish

Mike Tidwell, director of Chesapeake Climate Action Network, said at an October Maryland Commission on Climate Change meeting that the state’s draft Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Act, increases “the attractiveness of natural gas,” by utilizing the 20-year timescale.

Salawitch is optimistic about Pennsylvania joining the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a market-based cap coalition on greenhouse gases.

“Having Pennsylvania be a part of RGGI … means that one day we could do our best to limit leaks from the point of extraction (when drilling for natural gas) to the point of combustion,” Salawitch said.

“I’m proud of what we did for the state of Maryland, but there is still a lot of work to be done,” Dickerson said. “We are still emitting too much carbon dioxide.”

“I think methane may play a larger role than is indicated in there [the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act],” Dickerson continued. “But at least we are looking at it.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution