Every now and again, Gov. Larry Hogan exhibits the need to buff up his Republican bonafides as he often governs like a Democrat.

One of the ways he flashes the voters is to offer a regular harangue about the evils of partisan redistricting when his own GOP is guilty more so than Democrats. Hogan wants to depoliticize politics.

Right on cue, as the warm-up for the 2020 General Assembly gets underway, Hogan offered this year’s regurgitated meme to sponsor a remedy, Bill No. 1, he says, to replace legislative draftsmanship with a non-partisan panel of mapmakers. The plan, as he and everyone else knows, is headed for the shredder before it’s even drafted, as it has been consigned in its previous iterations.

The significance of its reintroduction this season is that it intersects with his call of a special election, as required by law, to fill the enormous shoes left by Rep. Elijah Cummings, who, as recently reported, died of thymic carcinoma a month ago.

Into the breach have stepped several ALL CAPs names and the usual gaggle of lower case adventurers who seem to appear at every opportunity. But that’s democracy in action.

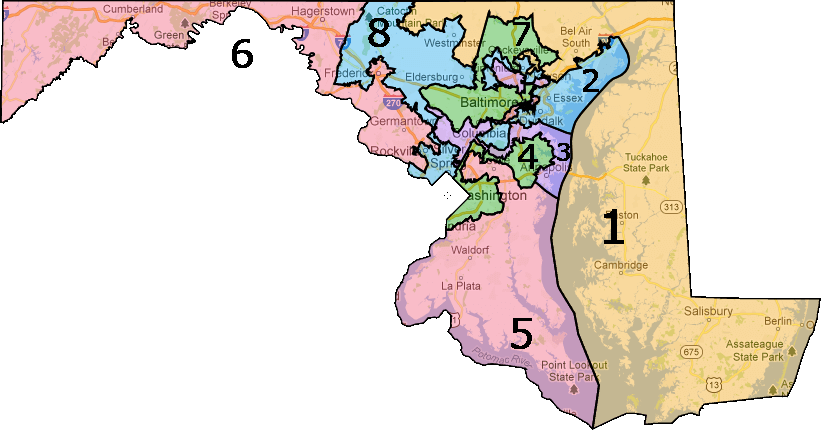

First, a refresher. Maryland is a misshapen mess, as for drawing maps. But to the point of Hogan’s screed, that doesn’t prevent slicing and dicing the state into eight, though perhaps awkward, packages of approximately 750,000 people each except for the pesky intrusion of politics and the silly notion that some folks believe redistricting should be fair.

When it gets down to Maryland’s 7th District, the Cummings legacy district, a whole different issue comes into play. The one area in which the courts have intruded into the sticky wicket of redistricting is that of minority representation.

Simply put, minority representation cannot be diluted or messed with. Any tampering with the Seventh’s minority advantage likely would wind up in court, and eventually the trash. The days of bleaching some districts to blacken others is under the watchful eyes of the courts, for whatever that’s worth. So the Seventh pretty much comes with a lifetime warranty attached.

The courts have, for the most part, removed themselves from the process they regard as purely political. Yes, they’ve rejected maps and ordered them redrawn, but the process remains, for the most part, out of the courts’ hands – undefined and left to the states.

The Constitution does not set the size of the House. The number of representatives grew and was hotly debated as the nation evolved. The size of the House was frozen at 435 under the Congressional Reapportionment Act of 1929. Thus, there are no established guidelines for redistricting except population balance. Each of the 435 districts should have approximately the same population. That’s about as fair as redistricting gets.

(It has been argued that the Supreme Court’s five conservative justices, most recently in the case of Maryland’s Sixth District, declined to act to protect other states where conservatives — Republicans — control redistricting.)

So, in a sense, the Seventh is sacrosanct. The shape of the district has been described frequently as resembling a prehistoric beast of various nomenclatures that defy spelling. Essentially, it looks like a runaway ink blot or one of those contrived spills in a paper towel mop-up commercial.

The Seventh Congressional district was created following the 1950 census, and it has been a majority black district since 1973. Originally it was a self-contained bubble within Baltimore City. Historically, the district was established in 1793 but abolished following the census of 1840. It was reinstated following the 1950 census. At the time, Baltimore was the nation’s sixth largest city, with a population of nearly a million. A state’s representation increases or decreases as population expands or contracts.

The Seventh had been considered essentially a Jewish District at a time when Baltimore had three intact congressional districts within its borders. It had been home base for several of the city’s prominent political organizations. But as the younger Jewish population began to decamp for the suburbs, blacks soon took up residence in the abandoned precincts and the spread to a minority district followed.

Frank A. DeFilippo

The first congressman to represent the newly reinstated district was Samuel Friedel, who served from 1953 to 1971. Friedel was defeated by 37 votes in 1970 by Parren J. Mitchell, in a three-way Democratic primary race that included state Sen. Carl Friedler. Mitchell represented the district until 1987. Kweisi Mfume succeeded Mitchell and was the Seventh’s congressman until he resigned in 1996 to take over the NAACP. Cummings was elected to the vacancy and served until his recent death.

Today, the land-mass of the Seventh covers about half of Baltimore City, which is 69 percent black, most of the black sections of Baltimore County and a majority of Howard County, which is 20 percent black. It’s important to remember, too, that in the Baltimore chunk of the district, black women are a powerful voting force.

So given Maryland’s bizarre Etch-a-sketch borders, along with mandatory minority representation, trying to please everyone in the redistricting puzzle, including Hogan, is no cinch.

Which is not to say that the district could not be reconfigured to accomplish the same outcome, but that, again, could throw the entire map out of kilter.

There are at least a dozen-and-a-half prospects, by rough count, who could join the joyous jumble that will make up the ballot for the Feb. 4, 2020, special election to succeed Cummings and who must meet the Nov. 20 filing deadline. The primary winners will run again in the previously scheduled April 28 statewide primary, which will act as the general election to serve the remainder of Cummings’ term. Daredevils who are optimistic about winning the primary can also file to run in the November general election for a full two-year term.

Foremost among them is Mfume, who held the seat for a decade and who compiled a solid record as a civil rights champion with access to the White House under President Clinton as well as chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus.

And by virtue of the name alone is Maya Rockeymoore Cummings, who resigned as chair of the Maryland Democratic Party to pursue the campaign theme that her husband wanted her to succeed him in Congress. She is a Ph.D and a former congressional staffer.

Del. Talmadge Branch brings wide recognition and a list of credentials that includes 25 years in the House of Delegates, now its majority whip, and former chairman of the Legislative Black Caucus.

Sen. Jill Carter is expected to declare her candidacy on Tuesday. If she runs, her calling card is the name and legacy of her father, civil rights leader Walter Carter.

As for the rest of the pack (no offense): Harry Spikes, a congressional aide to Cummings, is running for his old boss’s seat as a tribute to the lessons of leadership he learned working for Cummings; Kim Klacik, a Republican who trash-talked her way to recognition and President Trump’s Tweetstream about Baltimore being a dump that she’d now like to represent; William Newton (R); Reba Hawkins (R); Liz Matory (R); Dan Baker; Anthony Carter Sr. Darryl Gonzalez; Mark Gosnell; Michael Higginbotham; Charles Smith; and Charles Stokes.

“The race belongs not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong. But that’s the way to bet.” Anon, but the suspicion is H. L. Mencken.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution