A Change Agent in a Place Where Change Comes Slowly

Last in a five-part series on new leaders in the state’s five largest counties.

There’s a joke that Baltimore County Executive John A. “Johnny O” Olszewski Jr. (D) and his top staffers like to tell, with variations. The punchline is always the same: 1851.

That’s the year Baltimore County incorporated. And, the joke goes, county government has been doing things the same way ever since.

Changing county government – its priorities, the way it delivers services, and its internal culture – has been job No. 1 for Olszewski since he became county executive in December. In the halls of government in Towson, and to the people who follow local politics closely, the changes have been readily apparent, even dramatic.

“He’s not about business as usual,” said Sheila Ruth, a progressive and Democratic activist from Catonsville.

But whether those changes are radiating out yet into the community – where government has been run one way, and relatively competently, for as long as anyone can remember – is hard to say.

“Bringing about serious change in Baltimore County is like turning around a battleship – you don’t do it overnight,” said Don Mohler, who spent half a year as interim county executive following the sudden death of Kevin Kamenetz (D) in May of 2018 and worked for county government or the county schools for decades before that.

Yet Mohler said Olszewski’s desire to shake up the county is plainly evident and infectious.

“Johnny has energized 800,000 people to a sense that his slogan – ‘a better Baltimore County’ – can be a real thing.”

Olszewski, who turns 37 on Tuesday, is the youngest executive in the county’s history, and he’s certainly been ubiquitous since taking office. He rarely sits still.

During budget season, he held town halls in all seven County Council districts that attracted overflow crowds. He also held public meetings all over the county to get input as he looked to hire a new police chief. At the annual National Night Out last month, he hit events in Owings Mills, Randallstown, Halethorpe, Dundalk and Nottingham.

“He does get out to the community,” observed state House Speaker Adrienne A. Jones (D-Baltimore County), a retired county government employee. “He’s not just stuck in Towson.”

That’s no mean feat in Baltimore County, the second largest Maryland jurisdiction by geographical area – and arguably the most diverse, with industrial sections, horse farms, waterfront, traditional suburbs, urban areas and historically African-American enclaves. Moving around the county can be a physical challenge, and, occasionally, a political minefield – with countless constituencies to be mindful of.

“We will always show up,” Olszewski told the crowd at the Liberty Road Volunteer Fire Company in Randallstown during National Night Out. “We will always be here. We’re always a partner.”

Not exactly a landslide

Olszewski spent 8 1/2 years in the House of Delegates before being upset in a state Senate race in 2014 – a year that was a disaster for Maryland Democrats.

Last year, he won the four-way Democratic primary for county executive by just 17 votes; his general election victory, over state Insurance Commissioner Alfred W. Redmer Jr. (R), though competitive, was by a considerably more comfortable 15 points – and aided by a nationwide Democratic wave. This coincided with Republican Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. winning Baltimore County by 23 points.

The primary dynamic was unusual, and Olszewski was hard to peg as a candidate.

He’s a former public school teacher who has a Ph.D in public policy from University of Maryland Baltimore County. He’s a wonky progressive who comes from a conservative and largely blue-collar area of the county. His father, Johnny O Sr., was an old-school, back-slapping pol who served for 16 years on the County Council. While the younger Olszewski is long and lean, his father is barrel-chested and considerably shorter.

In the primary, then-County Councilwoman Vicki Almond, though she would have made history as the county’s first female executive, largely represented the status quo. She was the tightest with Baltimore-area developers, who have largely held sway in the county for the past several decades. And she was clearly part of the Towson political machine – with a political base not unlike Kamenetz’s.

Then-state Sen. James Brochin – a conservative Democrat who was often abrasively at odds with the party establishment during his tenure in Annapolis – preached an anti-development message and vowed to bring reform to county government.

Olszewski was something of a hybrid. He had far and away the most comprehensive and forward-looking policy prescriptions, and he worked hard to attract voters from outside his political base.

Significantly, he was the only major candidate who publicly embraced legislation to forbid housing discrimination in Baltimore County based on a renter’s source of income – an enduring cause of segregation in the county.

“I think voters were ready for something different,” Olszewski reflected in an interview.

The formula was just enough to prevail in the primary, and suggested to some political veterans – though not all – that the county might be changing, or at least receptive to change.

“The county is still very segmented,” Ruth said. “I’m not sure the county is changing so much as Johnny is good at navigating conflicts.”

On the campaign trail, admirers said, Olszewski seemed almost guileless.

“You can’t be around Johnny for a few minutes before you say, ‘this guy is really genuine,’” Mohler observed.

Kelly R. Carter, co-owner of the Grind and Wine Café in Randallstown and executive director of the Liberty Road Business Association, put it another way:

“The man who runs Baltimore County is no different than the man I’ve known personally for the last decade,” she said.

Shaking up the bureaucracy

County executives come and go. For years in Baltimore County, the government was dominated by one man: Fred Homan. He worked for county government for 40 years. He became budget chief in 1989, and in 2006, he became the county’s chief administrative officer, a job he held under three executives.

But just a week after his election, Olszewski made it clear that he wanted someone else in the job, and Homan retired. The result has been a significant culture change in county government.

Olszewski – benefiting from the fact that the state has been without a Democratic governor for two terms – surrounded himself with a team of smart, young operatives who might otherwise be working in the State House.

For chief administrative officer, Olszewski selected Stacy L. Rodgers, a veteran government administrator. For police chief, he hired Melissa Hyatt, a former Baltimore City police official who most recently worked as the head of security at Johns Hopkins. Olszewski has a record number of women and people of color in top positions, including a female fire chief.

“They’ve been good to work with,” County Councilman David Marks (R) said of Olszewski’s team. “Nobody’s in over their heads.”

More significant, in Olszewski’s view, is his attempt to empower county employees, who, in his words, had learned to “keep their heads down” under previous administrations.

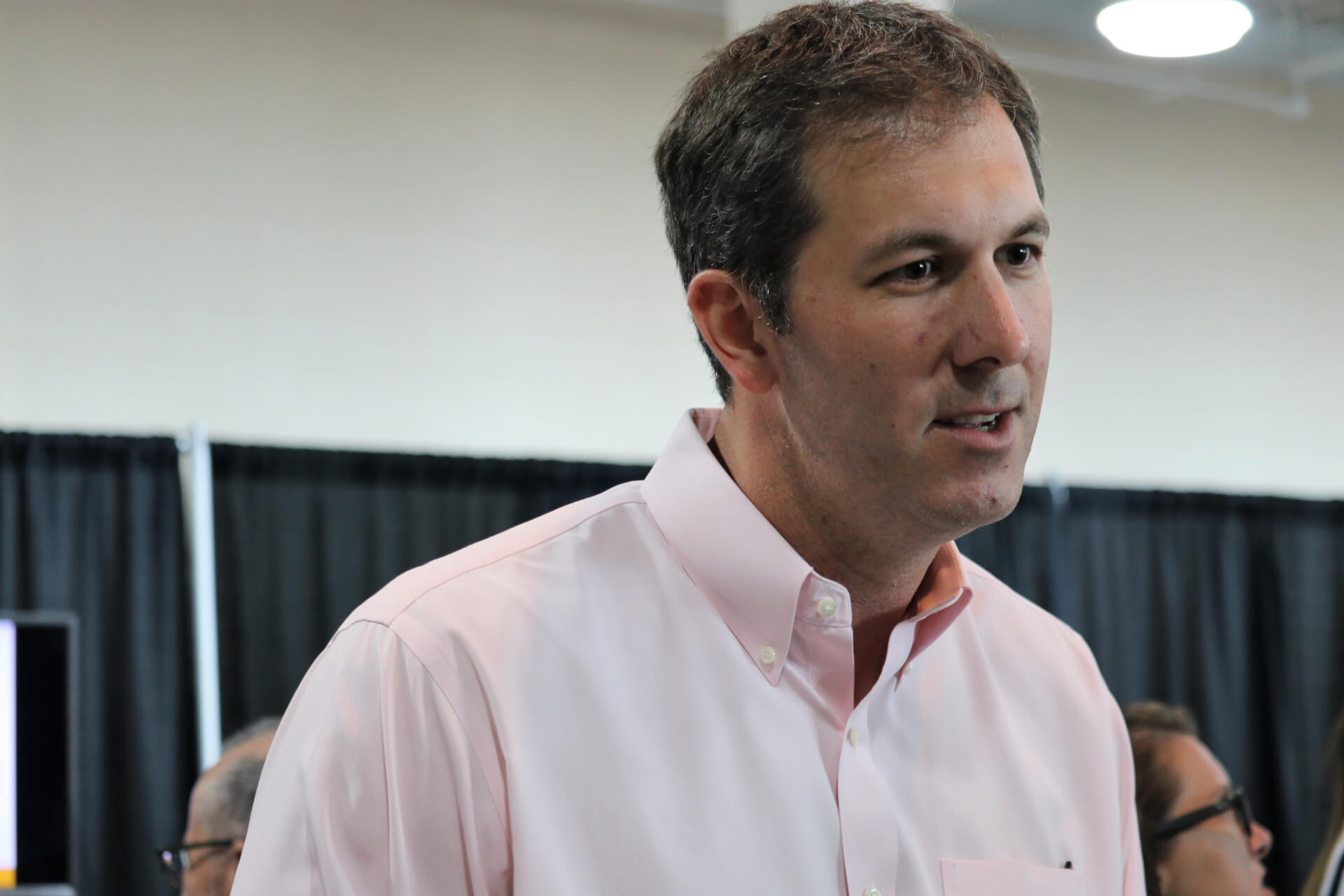

Baltimore County Executive John A. Olszewski Jr. (center) at a “Night Out” event in Randallstown last month. Photo by Josh Kurtz

For too long, he said, morale among county workers was low. County leaders have accepted the status quo in government – and as a result, so have Baltimore County residents.

Several veteran county officials, Marks said, “feel liberated.”

As a young policy wonk, Olszewski is also trying to make county government – and the way people evaluate it – as data-driven as possible.

“I wanted to make things more customer-centric, not so government-centric – from technology to mindset,” Olszewski said. “When you stay on autopilot, you’re not updating your technology, you’re not updating your processes, you’re not making changes. I didn’t think that was sustainable in the long haul.”

An early tax hike — and battles ahead

Olszewski has already encountered several tough policy challenges. First among them: a projected budget deficit of $81 million. So as Olszewski traveled around the county holding budget listening sessions and began meeting with key stakeholders, he quickly realized that he was going to have to try to raise taxes.

That hadn’t been done in Baltimore County in 30 years.

“The prevailing wisdom was, you couldn’t do something like this,” he said.

Asked during an interview in a sitting area of his office, near a portrait of War of 1812 hero Nathan Towson, when he came to the conclusion that he would have to raise taxes, Olszewski jumped up from the wing chair he was sitting in, rushed to his inner office, and emerged with a fat budget book from last year. He opened it to page 94 and pointed to a footnote at the bottom.

The previous year’s budget warned that there could be “a dramatic reduction of services” if county revenues didn’t keep up with county spending. Olszewski said he took this as a challenge, to make the case to the community why a tax increase would be necessary.

“The teacher in me got to present the facts and the consequences – here’s what I found,” he recalled. “We were at a crossroads. We were transparent about where we were. And people were great about it.”

Not surprisingly, no one was clamoring for service cuts. In fact, “everyone I talked to had a wish list, and everyone spoke to the county’s historical lack of investment,” Olszewski said.

Eventually, the administration and County Council settled on an increase in the county piggyback income tax and a hike in the county cell phone tax.

Olszewski’s budget passed by a 6-1 vote on the County Council, with two of the Council’s three Republicans joining with all four Democrats to vote for it.

“It was smart for him to push for tax increases in his first year,” Marks said. “It will give him time to point to things that he’s achieved” with the extra funding.

Olszewski has made school construction a top priority. Just last week he announced new planning and design money for new Dulaney Valley and Towson high schools – projects that members of the community have been seeking for years. Olszewski said there is a 10-year plan in his budget that forward-funds several school building projects.

Olszewski’s desire for more school construction funding aligns with Jones’ No. 1 priority – and the county expects to benefit from the speaker’s newfound power in Annapolis.

Marks suggested that in the long run, failure to show progress on the school construction front would be a bigger political peril for Olszewski than his push to raise taxes.

But more policy challenges await: Under a Department of Justice order, the county must attempt to pass anti-housing discrimination legislation this fall – something Olszewski’s two most recent predecessors were unable to do.

“That’s going to be a difficult lift,” said Ruth, the progressive activist.

Olszewski also has a long list of other goals for the months ahead:

He hopes to make development in the county – and the operations of county government – more sustainable. He’s focused on what he calls “the hard work of infill development” and of maintaining the county’s infrastructure. He wants to create a public transit system. He frets about the obligations of the county’s retirement and pension system. He has hired a former colleague from the legislature, Eric Bromwell, to head the county government’s efforts to battle the opioid crisis. And like all Baltimore County executives, he’s keeping a wary eye on crime in the county – and in Baltimore City.

Olszewski said he’d rather confront these problems than ignore them, which he believes officials had a tendency to do in the past because county government in general was running smoothly.

Several political professionals wonder whether Olszewski would consider running for governor in 2022, when Hogan will be term-limited. He’s got a politically savvy team around him, and a high-profile platform as county executive that garners regular media attention in the Baltimore area.

But while several county executives have sought higher office in recent Maryland history, most have preferred to wait until they are at least into their second terms; a first-term statewide run could be awkward, and Olszewski and his team have tried to brush off any suggestions of greater political ambition at this early stage.

Yet Olszewski is scheduled to be the keynote speaker at a Wicomico County Democratic Central Committee dinner on Sept. 26, which suggests he’s not going to turn down an opportunity to up his political profile.

But for now, Olszewski’s advisers say, it’s all about bringing change to Baltimore County.

Watching Olszewski move through the diverse crowd outside the firehouse in Randallstown last month, Carter, the local business leader, nodded approvingly.

“Not only does he talk about change, you can see we’re in the midst of change,” she said. “You can gauge that we’re not the same Baltimore County that we were even a year ago.”

For our look at Prince George’s County, click here.

For our look at Anne Arundel County, click here.

For our look at Montgomery County, click here.

For our look at Howard County, click here.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution