In the grammar of politics, the election of two-term Gov. Harry R. Hughes was a predicate. It evolved on conditions and “ifs.”

If Blair Lee III had accepted Hughes as a running-mate in 1978, as Lee wanted and Hughes pleaded, the course of history might have been changed.

If Marvin Mandel had not appointed Hughes as Transportation secretary, as Hughes requested and Mandel later regretted, there might not have been the subway controversy that forced Hughes’ resignation as head of Maryland DOT and the scandal it provoked.

If Hughes had remained in the Senate, where he was majority leader and Finance Committee chairman, he would have lacked the issue and platform that launched his campaign for governor.

If The Baltimore Sun had not published a controversial poll a few days before the primary election, Lee probably would have squeezed out a victory, according to his own polling at the time.

And if Lee had not insisted on holding a news conference 10 days before the election at which he refused to divulge the source of a sizeable chunk of campaign cash, he might have carried the election with a higher turnout and a better vote in his home county of Montgomery.

But Hughes won. That’s the joyous jumble that is politics.

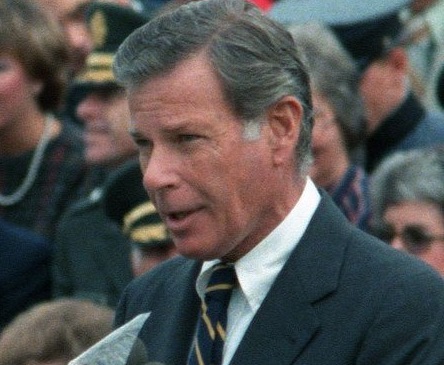

Hughes was the unlikeliest of candidates but the right governor at the right time. Bright, easygoing and laconic, he was a calm and calming presence in a state that had been racked by scandal – Agnew, Mandel, Alton, Anderson – until late in the game when he was whacked by his own grief, Maryland’s second savings and loan collapse.

The Hughes alchemy? Under-exposure is often preferable to over-exposure.

As a majority leader of the Senate, and chairman of its Finance Committee, Hughes, by the standards of the era, was a liberal, an anomaly for an Eastern Shore legislator from Caroline County. And his name was attached to many of the significant reforms of the time, none more notable than the revolutionary Cooper-Hughes-Lee (yes, that Lee) tax package that figured a way to equalize money: It transformed Maryland from a flat tax rate to a progressive income tax system.

The epic change had been shelved in 1966 while J. Millard Tawes was still governor but enacted in 1967 during Spiro T. Agnew’s first year in office. (Tawes insisted on being remembered for two achievements as governor – no tax increase and a budget that he kept under $1 billion. As a reference point, the budget working its way through the General Assembly is $46.7 billion – an increase of nearly a billion a year since Tawes’ days.)

And when it came time for Agnew to leave for Washington and the vice presidency, Hughes was among the seven candidates vying to succeed him as governor, along with House Speaker Mandel, who, as every political hobbyist knows, won the right to succession by a wide margin.

Hughes had dropped his candidacy the night before the election. (Interestingly, 60 years later, the faded “blacksheet” (carbon copy) of my advance story on the General Assembly election was recently re-discovered, completely by accident, neatly folded in the carrying-case jacket of my portable Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, journalism’s workhorse in the 1960s and now a collectable artifact.)

In the early 1970s, as Mandel, now governor, undertook the reorganization of the executive branch into a modern cabinet system, Hughes came to Mandel’s office one afternoon on what was expected to be a routine visit by a legislative leader.

Frank A. DeFilippo

Instead, Mandel got a surprise and an offer he couldn’t refuse but would later regret. Hughes said his law practice has suffered because he spent so much time on legislative and political business. Hughes doubled as chairman of the Maryland Democratic Party.

Hughes said he’d be willing to resign from the Senate in exchange for a cabinet secretariat. Such a move, Hughes reasoned, would give Mandel a two-fer – appointment of a successor as party chairman and maneuver a close ally into the position of Senate majority leader.

Mandel seized the opportunity. He asked Hughes which cabinet department he’d like. Without missing a beat, Hughes said transportation. Hughes was put on the executive payroll long before the transportation department was even approved by the General Assembly, with orders to come up with an organization plan for the diverse modes and assorted pieces.

To help design the new department, Hughes convinced Mandel to hire Lowell K. Bridwell as a consultant. Bridwell, a former reporter, had been federal highway administrator in the administration of President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Eventually, they came up with a department that was unique in the nation. It was organized around a unified transportation fund and a statewide network that eventually would include a Baltimore Area Metro System.

A half dozen years later, the Baltimore subway scandal hit with a resounding splash. Hughes resigned as transportation secretary, claiming there had been “tampering” with the multimillion-dollar contract. It wasn’t long, a mere seven weeks, before Hughes announced that he was running for governor. Several recollections creep out from the cobwebs:

The Baltimore Metro System might have had the appearance of a gift to the city and its mayor, William Donald Schaefer, but it had little to do with getting from here to there. The massive construction project, involving an estimated 2 million man-hours of work, was a payoff to the building trades unions and its president, Ed Courtney, for their political and financial support of entrepreneur Irv Kovens’ clubhouse of candidates, which included Mandel and Schaefer. (Agnew earlier had pushed for a subway system with rubber tires instead of steel wheels, which was built by only one company – Westinghouse – and headed by a close friend and supporter.)

Dale Hess, a Mandel factotum and financier – Mandel’s fixer, in current parlance – had arranged a fundraiser in Los Angeles for Mandel with an engineering company that was competing for all or part of the contract.

And the canny Sen. Harry “Soft Shoes” McGuirk, who had memorably described Hughes’ candidacy for governor as “a lost ball in tall grass,” was maneuvering behind the scenes on behalf of Victor Frenkil, a Baltimore contractor who was well-known for cost overruns on his construction projects.

And Mandel, who had no patience or fondness for Frenkil, was suddenly chummy and socializing with the very man he disliked. (McGuirk was christened “Soft Shoes” by Sen. Joseph Bertorelli, of Baltimore, who observed of McGurik: “He kind of sneaks up on you like he’s wearing soft shoes.”)

From its start, Hughes’ candidacy was heading straight toward the dumpster. By that time, Mandel had surrendered the governorship to Lee, as required by Maryland law, while he awaited sentencing for conviction on unrelated crimes. Lee was now acting governor and the leading candidate for the open seat in 1978.

Hughes had appealed to Lee, his Senate comrade, on several occasions to choose him as a running mate for lieutenant governor. Lee was eager to agree to the arrangement, which would produce a solidified a ticket and taken Hughes out of contention for the governorship. Only Ted Venetoulis, executive of Baltimore County, and Walter Orlinsky, Baltimore City Council president, would remain as competitors. (Orlinsky joined the race to draw votes away from Venetoulis.)

A meeting was set at the State House between Lee’s advisers, many of them Mandel retainers, and Prince George’s County political boss Peter O’Malley and his wingmen, who had been promoting Rep. Steny H. Hoyer (then president of the Maryland Senate) as a running-mate on a Lee ticket.

It was at that meeting that a deal was brokered. Word was sent to Lee that if he chose Hughes as a running-mate, the entire Mandel organization would bolt from his campaign and leave him without the manpower to continue his run for governor. Lee reluctantly submitted to the blunt threat and agreed pair up with Hoyer.

In the final weeks before the September primary election, Bradford Jacobs, editorial page editor of The Evening Sun, spent time meeting with Hughes and working to convince his publishers and fellow editors that Hughes was a viable candidate.

The newspapers repeated front-page editorials endorsing Hughes. They then ran a poll in the final days which was suspect because its findings were surprisingly out of line with other polling. It showed Hughes with a chance of winning. Lee’s polls, conducted by Joseph Napolitan, one of the nation’s premier political pollsters, had Lee out front by a modest margin. The Lee camp was confident.

But it was The Sun’s poll, more so than its editorials, that shifted the tide in Hughes’ favor. It reinforced the sense that Hughes’ could be elected by those who were seeking a sanitizing alternative to the string of scandals and embarrassment of the previous decade.

On election day, Hughes’ voters dominated at the polls while Lee’s nominal supporters either stayed home or skipped over his name, especially those in his home county. Lee carried Montgomery County, but far short of the anticipated margin where for years his father had been the supreme political boss.

Hughes’ governorship was an accident destined to happen. RIP Harry R. Hughes.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution