Peta N. Richkus: State Should Reinstate the Retirees’ Prescription Benefits They Were Promised

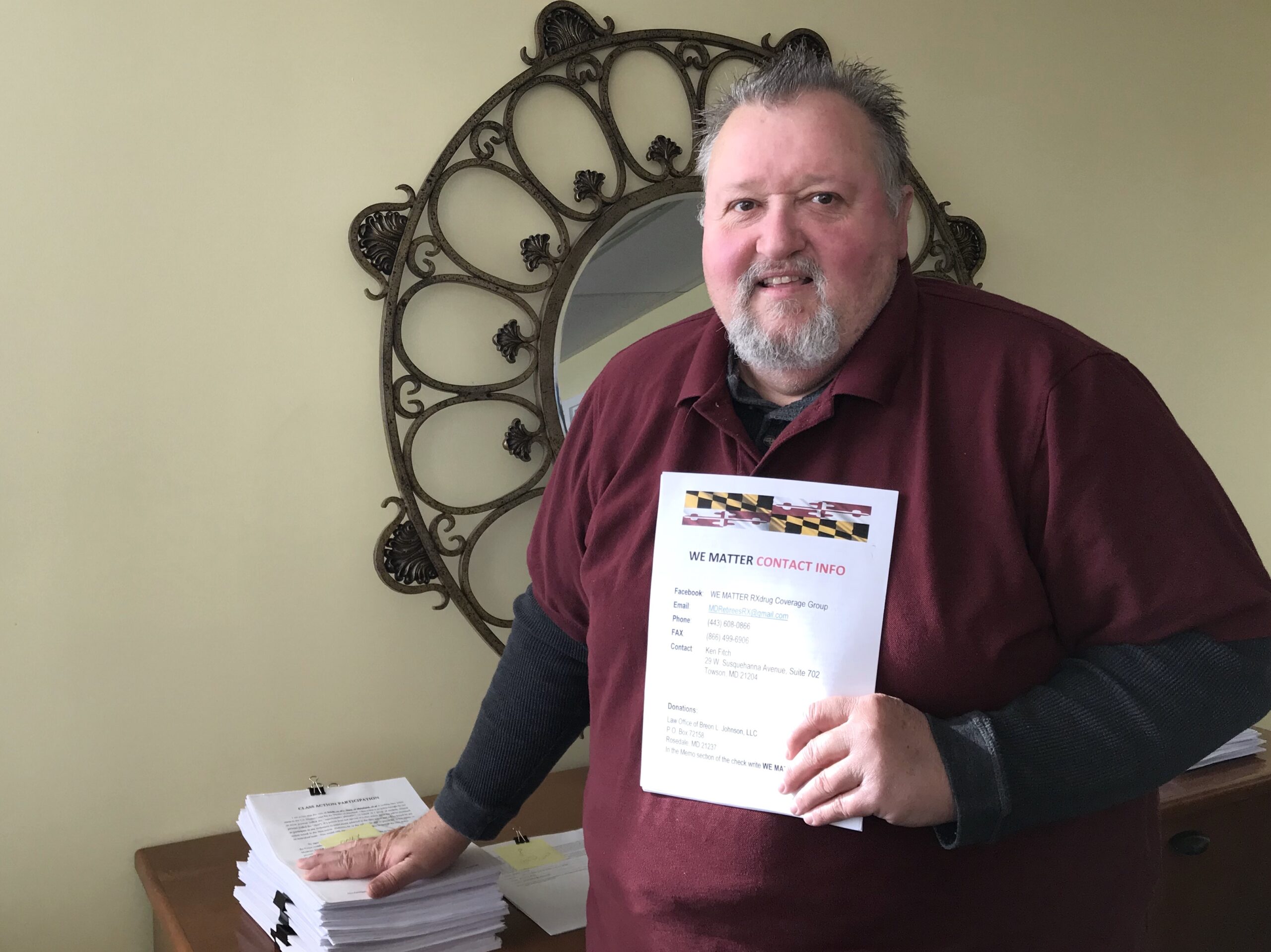

UPDATED: Retired state employees owe Ken Fitch and attorneys Deborah A. Holloway Hill and Breon Johnson a huge debt of gratitude. [“Leading the Fight to Restore Retirees’ Drug Benefits” by Danielle E. Gaines, Feb. 27, 2019]. Thanks to their diligence, and encouraged by thousands of state retirees, on Oct. 10, 2018, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland granted a preliminary injunction in favor of the retirees.

As a result, state retirees did not have to sign up for Medicare Part D by Jan. 1, 2019, and the state shall continue retirees’ prescription drug coverage until the case concludes. As Gaines’ article makes clear, Mr. Fitch, Ms. Hill and outraged retirees are continuing to fight for what was promised to them in the terms of their employment with the state of Maryland and at the conclusion of their state service.

Some history

The state’s efforts to strip its Medicare-eligible retired employees of their prescription drug coverage over the past eight years is a long story, over several administrations, and involving the concurrence of several sessions of the General Assembly.

Governors and their secretaries of the Department of Budget and Management welcomed an opportunity to eliminate an expensive – but earned, promised and codified – benefit because doing so freed up budget resources to invest in other programs without a need to raise additional revenues.

The legislature, too, was glad to have more budget resources to apply to other state programs without the pain of increasing fees or taxes. Thus, in 2011, members of the Maryland House and Senate passed an amendment (Chapter 397) to the Maryland Code (COMAR17.04.13 – State Employees’ Health Benefits) to increase the out-of-pocket limits for participating employees.

That brought an immediate savings to the state. The amendment realized even more OPEB — Other Post-Employment Benefits: the benefits, other than pensions, that a state or local government employee receives as part of his or her package of retirement benefits — savings by moving Medicare-eligible retirees completely out of the state’s plan in 2020.

In 2017, in another “money-saving” action, the “move out” date for Medicare-eligible retirees was accelerated by the administration and the General Assembly to January 2019. Having convinced themselves that their actions were doable, justifiable and prudent, they eliminated, for them, a troublesome financial obligation by dumping it squarely on the backs of state retirees.

But the state’s action was not right, as recognized last October by a federal judge. And the state’s case to strip retirees of their prescription drug coverage, as presented in the Department of Legislative Services’ Fiscal and Policy Notes on this session’s crop of related bills, is not right either.

The analysis is skewed to support the state’s position over the last eight years and to defend its stance in the still-pending federal court case.

Fairness and justice

Yes, there is a growing cost to all aspects of the state’s compensation plans. Just as there is an increasing cost to the 16 percent raise voted by and for members of the General Assembly and as recommended in 2013 by the General Assembly Compensation Commission. Well-deserved, no doubt, after four years without any salary adjustment.

But it should also be remembered that there were many years — over 20-, 30- and 40-year careers — that now-retired state employees saw no pay increase and were also subjected to various sleight-of-hand maneuvers by the state to reduce their take-home pay and benefits.

Benefits, including health care coverage, are understood to be a part of any organization’s employment/compensation agreement, a contract between the parties. Both the scope of the job and the compensation package (salary and “fringe benefits”) are mutually agreed upon.

In this case, the state health insurance benefit plan, established by state statute, was part of the agreement. By its actions, the state has reneged on the agreed-upon terms set in state law with disastrous consequences. Especially for those state employees who retired before the enactment of the infamous Chapter 397 in 2011.

Oh, by the way, state employees who retired during this period do not remember any information about this change to their promised benefits being given to them by DBM’s Office of Personnel Services and Benefits nor explained in their pre-retirement seminars as they transitioned to retired status.

This year’s bills and fiscal and policy analyses

Thankfully, retirees have organized around this issue, have educated themselves on the details and have contacted their elected officials. As a result, many members of the House and Senate are working to address the problem.

House Bill 98/Senate Bill 193 is the proposed legislation supported by a majority of retirees because the bill restores prescription drug coverage for retirees of the state under the State Employee and Retiree Health and Welfare Benefits Program. HB 98 has 57 sponsors; the corresponding SB 193 has 47 sponsors.

Several other bills are under currently under consideration but found wanting by retirees: HB 490 (13 sponsors); HB 979 (12); HB 1004 (14); HB 1033 has a single sponsor; and HB 1120 has 18 House sponsors, and two on the cross-filed SB 946. No doubt these unsatisfactory versions are being pitched as “part of the solution” to the dilemma of the retirees’ prescription drug plan mess. They are not.

Retirees were very disappointed that the already-once-rescheduled hearing on HB 98 was canceled, reportedly because of “the price tag” cited in the fiscal and policy note. The note for HB 98 appears tailor-made to support the administration’s agenda during the legislative session as well as in the federal court case now pending, rather than present an objective consideration of the state’s obligation to its retirees.

From the beginning, the Department of Budget and Management has raised a couple of red flags, including possible damage to Maryland’s enviable bond rating.

However, when retired University of Baltimore professor Edward R. Kemery contacted them, neither Moody Analytics (one of the primary bond rating agencies) nor Odyssey Advisors (actuarial consultants for both the public and private sectors) were able to cite any examples of a state’s bond rating being downgraded due to OPEB liabilities even though, yes, the liabilities are among the factors considered in the bond rating process. The more important rating factor is whether or not the state adequately funds its pension and OPEB liabilities.

The Department of Budget and Management, over various administrations, has manipulated the state’s level of contributions: it’s a very handy tool to make the rest of the governor’s budget meet the balanced budget requirement. Gov. Larry Hogan said in his February 2017 State of the Union speech that he worries about the state’s pension system’s $20 billion unfunded liability.

How worried can he be since his recent actions on the matter include withholding a mandated $50 million supplement to the state retirement and pension system in his fiscal 2018 budget?

Governmental Accounting Standards Board rules are another “red flag” raised. GASB is the source of generally accepted accounting principles used by state and local governments and also cited in the fiscal and policy notes. However, Dr. Kemery’s research did not find any evidence that the GASB reporting changes referred to in the notes have any real impact on bond ratings.

On the contrary, some public finance attorneys have opined that the “new” (2014) change in GASB reporting standards has had virtually no impact on credit ratings:

“It is our view that much of the hand-wringing over the issue is overblown, and that the new GASB reporting scheme will not materially affect the credit ratings of most public plan sponsors. This is because the rating agencies themselves have signaled their understanding that the new GASB reporting rules might be mere window dressing that, ultimately, does not change the already apparent realities of the marketplace.”

Additionally, the analyst’s notes neglect to point out that GASB unambiguously states its position on funding OPEB liabilities:

“… the GASB believes that a government has an obligation to pay OPEB based on the level of retirement benefits promised to an employee in exchange for his or her services.”

In considering all of the related bills, our legislators should not rely on the accompanying fiscal and policy notes, based on information provided by DBM, without separate and independent analyses.

Peta N. Richkus

What is a contract?

While in the workforce, if and when the terms of one’s compensation package are changed, an employee has the option to accept them or to seek other employment to meet their needs and those of their family.

Retirees, especially “Medicare-eligible” retirees, have no such option. For these older retirees, the time to budget, plan and save is long gone. This “stealth” change to state retirees’ prescription drug plan is a financial and health care disaster for state retirees.

It is equivalent to a significant reduction in income for the majority of those retirees affected – 60 percent of them, even by the Department of Legislative Services’ analysis. In a close reading, the notes are found to contain questionable assumptions, misleading statements, and over- or understated numbers. For example, the notes state that there is no fiscal effect in fiscal 2019 related to any of the proposed bills. How can that be even though the state continues to cover the retirees’ prescription drug plan as ordered by the court?

Other changes in state employee benefits will be necessary going forward. But the state should live up to its prior commitments. Current retirees should not be subjected to retroactive cuts to their benefits. To do so is to “claw back” compensation as if state retirees had not lived up to their side of their employment agreement.

This is patently not true. They lived up to their part of the contract. So must the state.

Members of the General Assembly face a challenging situation. Especially knowing that, sooner or later, they will join state retirees who all have a right to count on the benefits they were promised.

The only fair and just response is to reinstate the state retirees’ prescription benefit plan.

— Peta N. Richkus

Peta N. Richkus of Towson was secretary of the Maryland Department of General Services (1999-2003) and port commissioner of the Maryland Port Administration (2008-2014).

This story was updated at 1:30 p.m. March 5. The original version contained incorrect information regarding the state budget. Funding is in Gov. Larry Hogan’s budget to continue with retiree pharmacy benefits in the same way they were funded last year.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution