In Debate on Campaign Finance Reform, It’s Reformer vs. Reformer

They sat side-by-side during a series of short Senate hearings Thursday, testifying in favor of election reform bills dealing with absentee ballots, campaign finance reporting periods, and early voting.

But when it came to the question of whether there ought to be a national constitutional convention to address the scourge of money in politics, the same representatives of reform and good government groups couldn’t be farther apart. And what started as a difference of opinion has, over the years, turned very acrimonious.

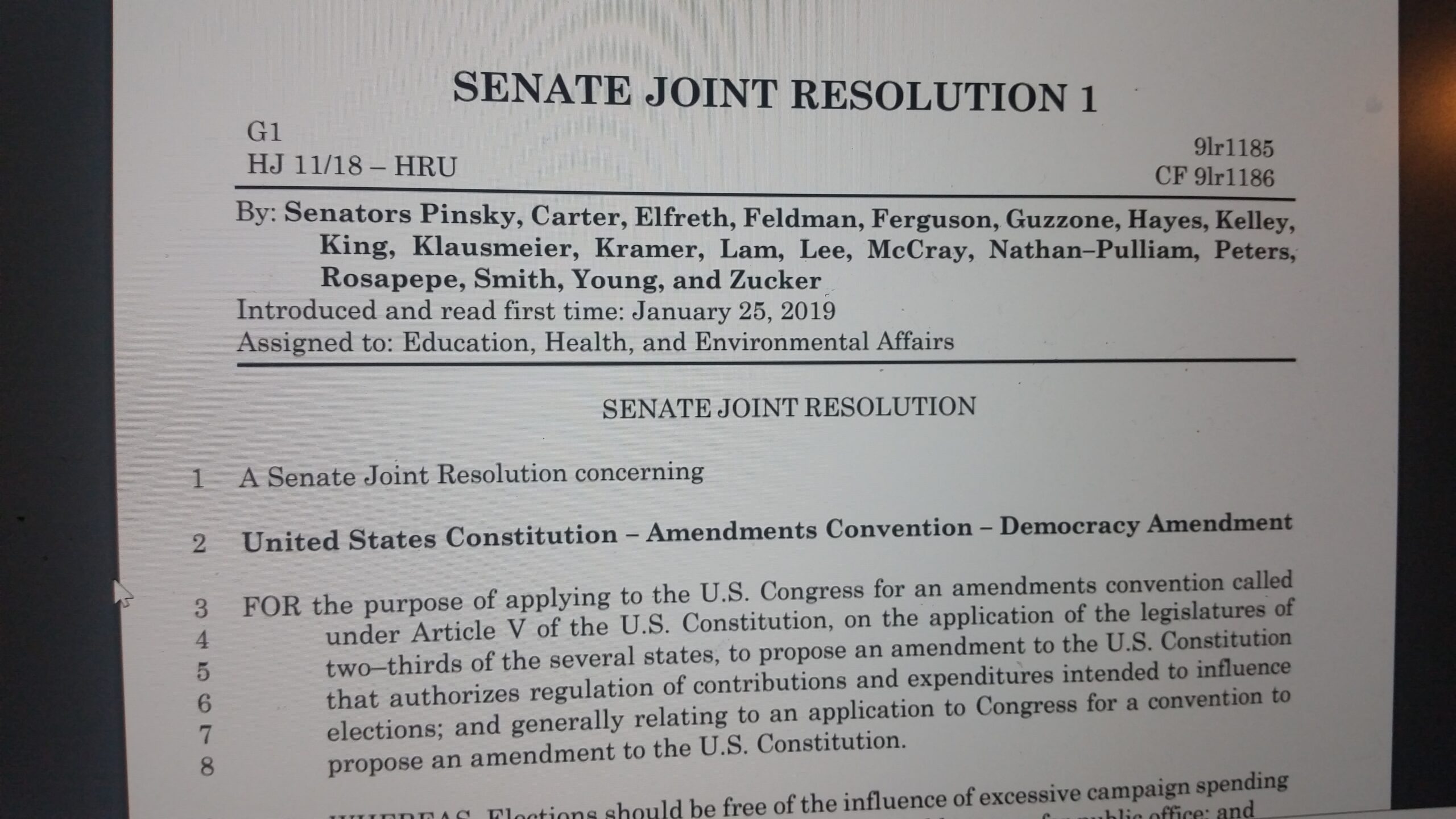

At issue is a resolution sponsored by Sen. Paul G Pinsky (D-Prince George’s) that would enable Maryland to call on Congress to establish a constitutional convention to set campaign contribution limits in the country. Five other states have already called for a constitutional convention on campaign finance laws; two-thirds are needed for Congress to act.

Political reformers who support a constitutional convention and those who oppose it agree that the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision unleashing unlimited corporate contributions into the electoral system has had disastrous impacts on the political process must be overturned.

“When we see elections of millions and billions of dollars primarily coming from the corporate sector, the concerns of the average voters are not being heard – they’re being drowned out,” Pinsky, the chairman of the Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee told his colleagues at the hearing on his measure.

Pinsky said he introduced the resolution because there simply isn’t a better way to begin chipping away at Citizens United. A constitutional convention would “initiate the public conversation about money in politics.”

“We don’t foresee Congress, at least for the next two years, taking any action,” he said.

For several years in Maryland, a grass-roots group called Get Money Out has been pushing to get state officials to call for a constitutional convention. The resolution passed the state Senate in 2015, but never went further. It passed in the House last year, but did not get through the Senate.

Pinsky has spent years working to limit the influence of money in Maryland politics. He has proposed public financing for legislative elections, greater to disclosure of donors, and has won fierce allies in the reform movement – some of whom support the call for a constitutional convention, others who support it.

“What we have now is the era of the billionaire,” said Charlie Cooper, president of Get Money Out.

Mike Tidwell, director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, said the impacts of money in politics are plainly visible in Annapolis.

“You can be at Harry Browne’s and elsewhere and you can see the scores of lobbyists for utilities and the American Petroleum Institute” dining with lawmakers, he said.

Opponents of the idea of using a constitutional convention to confront the issue of money in politics believe going to a convention is simply too risky, because they fear other issues could also come to the fore during these public discussions – with unintended and potentially harmful consequences.

“A constitutional convention is a dangerous and irresponsible path,” said Damon Effingham, executive director of the watchdog group Common Cause Maryland.

There has never been a constitutional convention in the 231 years of the republic. So there are legal theories and arguments on both sides about what a constitutional convention might look like and how limited the scope of issues would be. But nobody knows for sure what might happen.

Conservative groups have agitated through the years for a constitutional convention to discuss a balanced budget amendment and ways to restrict abortion rights, among other initiatives.

Effingham suggested that there are better ways to fight the influence of money in politics than a constitutional convention – and that Marylanders are already taking steps to do so. He cited the public financing system for campaigns that Montgomery County used in the 2018 election cycle, and noted that Baltimore City, and Prince George’s and Howard counties plan to implement public financing as well.

“As an advocate, I can barely keep up with the explosion of interest” in public financing and greater disclosure, Effingham said.

He also spoke enthusiastically about HR 1, a wide-reaching package of political reforms in the U.S. House of Representatives sponsored by Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.), calling it “an alternative organizing strategy.”

Other opponents of Pinsky’s measure include the League of Women Voters, AFSCME, and the left-leaning Maryland Center on Economic Policy. They noted that the General Assembly in 2017 rescinded a long-standing open call in Maryland for a constitutional convention.

But Pinsky and other advocates of a constitutional convention believe the process of attacking big money in politics, particularly at the federal level, will be painstakingly slow. And they argue that a convention can be limited to a single topic.

Beyond the tactical and political arguments, some of the reform groups on opposite sides of this issue are starting to hate on each other.

At one point during the hearing on Pinsky’s resolution, Sen. Clarence Lam (D-Howard and Baltimore County) noted that Wolf-PAC, a national political action committee seeking a constitutional convention on political spending, has spent money in Maryland political races and in one case targeted a former state Sen. Barbara A. Robinson (D-Baltimore City) in the 2018 Democratic primary. Lam asked how a group dedicated to reducing the influence of money in politics could justify spending money on political races.

“We’re going to use all tools in the current system that are available to us,” said Michael Monetta, Wolf-Pac’s national director. Robinson had abstained during a committee vote on the constitutional convention call in a previous legislative session.

But some of the reform groups opposing the constitutional convention have begun attacking Wolf-Pac’s fundraising and political activity.

Meanwhile, an attorney for Wolf-Pac noted that it is nearly impossible to determine who Common Cause’s top donors are. Common Cause is a national nonprofit group and does not endorse candidates in political races. Like all nonprofit groups, Common Cause must make certain financial information public, but does not list every contributor.

Effingham, in an interview, said examining the structure of the two organizations is an apples-to-oranges comparison.

During the hearing, Effingham apologized to Pinsky for opposing his measure.

“You, Chair, have been a fantastic leader on this issue, and on this one item, we just disagree,” he said.

Pinsky seemed embarrassed.

“Not necessary,” he said.

Pinsky’s resolution has 19 co-sponsors, all Democrats. A companion measure in the House is sponsored by Del. Tawanna Gaines (D-Prince George’s) and has 74 Democratic co-sponsors. Her resolution is up for a hearing in the House Rules Committee on March 4.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution