Cyberbullying Bill Sails Through Senate, Faces Questions in House Committee

The Maryland Senate gave unanimous approval Thursday to a cyberbullying bill named to honor a Woodbine teenager who took her own life in 2012 after online abuse.

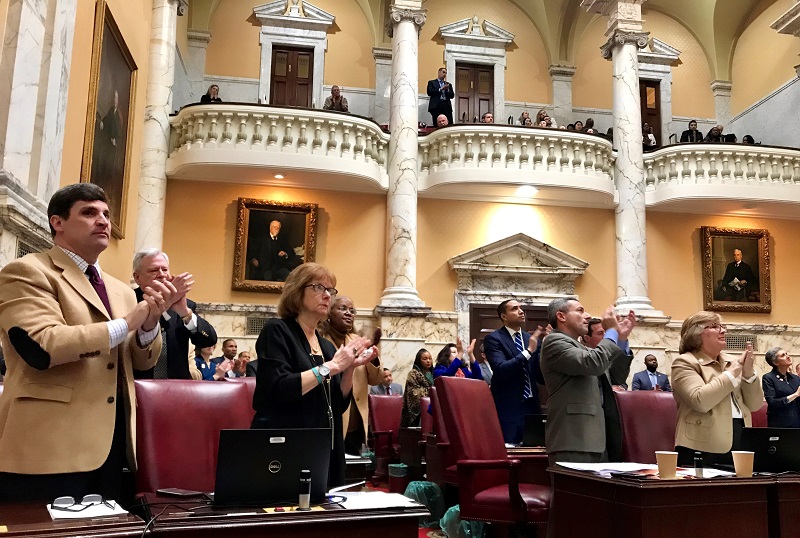

The entire Senate stood to give an ovation to Christine McComas, who has advocated for years alongside her husband, Dave, for greater laws to protect children like her daughter, Grace.

“Thank you, Mrs. McComas for your dogged advocacy,” Baltimore County Sen. Robert A. Zirkin (D) said, as his colleagues rose around him.

Zirkin is chief sponsor of Grace’s Law 2.0, which substantially expands a law that criminalized cyber harassment in 2013.

The 2013 law had a maximum penalty of a year in jail and a $500 fine. The new bill increases the punishment to up to three years in prison and a $10,000 fine, and also expands the ability of prosecutors to pursue cases for online abuse.

At a Senate hearing last month, Zirkin read some of the messages that had been directed at Grace on Twitter. Even though she wasn’t a member of the social media platform, the messages posted there were amplified and relayed back to her by classmates. Del. Jon S. Cardin, sponsor of the cross-filed House Bill 181, read them again to the House Judiciary Committee on Thursday afternoon:

“Snitches need to have their fingers cut off one by one while they watch their families burn.”

“I hate, hate, hate, hate, hate, hate, hate you. Next time my name rolls off your tongue, choke on it … and DIE.”

Christine McComas said her family sought help through the authorities but at the time of Grace’s experience, there were no laws to help. And today, with the advancement of technology such that it is, Maryland’s once groundbreaking law is in serious need of an update, the bill sponsors said.

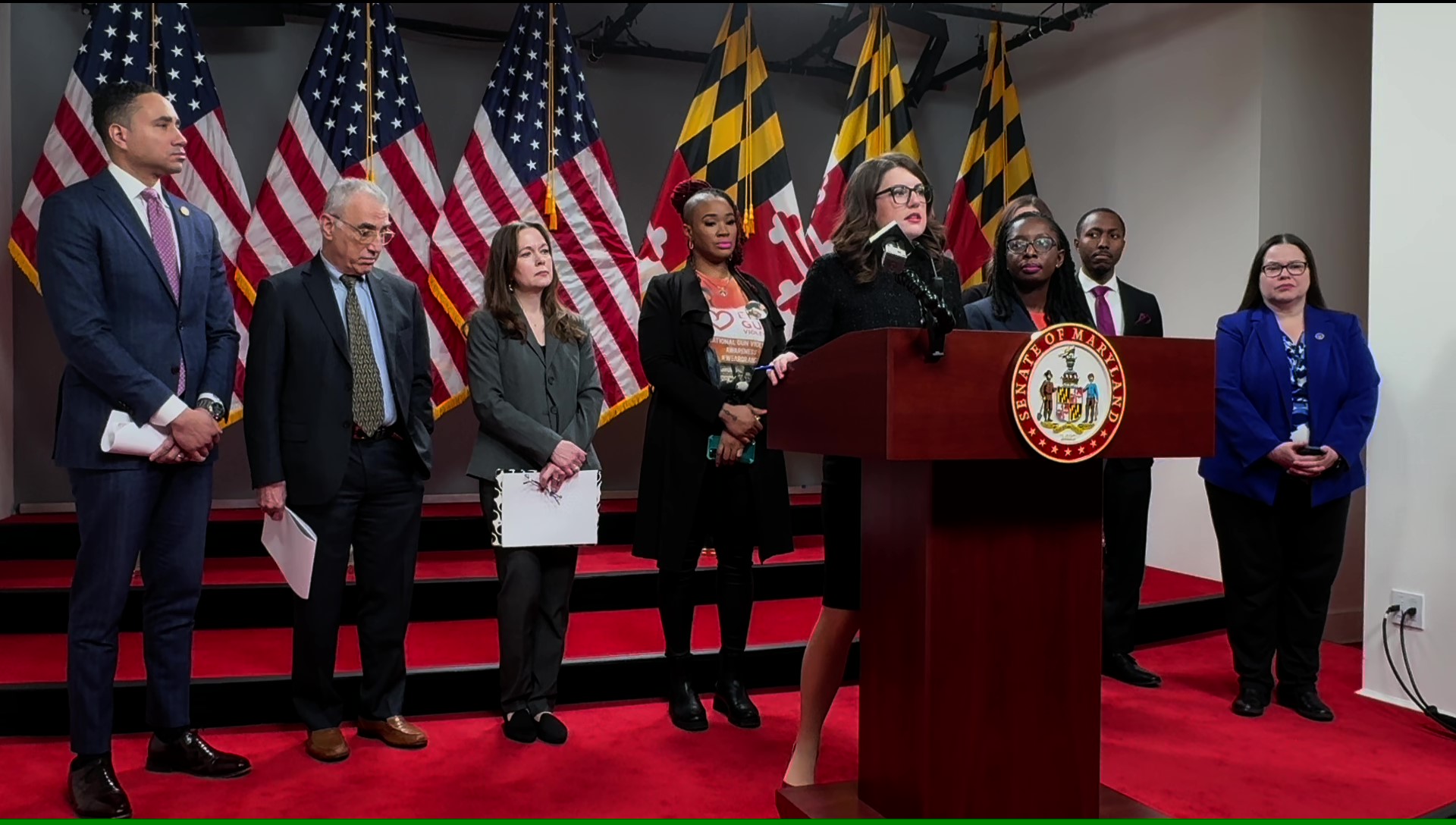

The measure passed the Senate 45-0 on Thursday morning. By the afternoon, the Senate’s amended version of the bill was being debated at the House Judiciary Committee, where some members were clearly moved emotionally by the stories of the McComas family and of Linda Diaz, whose daughter Lauryn Santiago took her own life in 2013 at the age of 17 after intense online harassment about her sexuality.

Last session, the bill also passed the Senate unanimously but stalled in the House Judiciary Committee after an intense lobbying campaign by the American Civil Liberties Union, which has argued that provisions of the legislation violate the First Amendment. The same concerns were reiterated this year, but the Judicial Proceedings Committee made changes to the bill to address some of the concerns.

The amended bill takes out requirements in current law that a harassing message must be sent directly to a victim and language that required a continuing course of conduct. The new law would allow prosecution for a single, significant act that has the effect of intimidating, tormenting or harassing a minor and which causes physical injury or serious emotional distress to a minor to be prosecuted if the actions were malicious and had the intended effect.

“It’s not a deterrent on their speech. It’s a deterrent on their conduct,” said Zirkin, who argued that the bill is now drafted “as tight as it gets.”

But Toni Holness, public policy director for the ACLU of Maryland, said the organization still has concerns. She said the new definition of electronic conduct ― a 100-word multi-part provision that includes building a fake social media profile and instant-messaging services ― is too wide-ranging and could include actions that don’t constitute a “true threat” under existing law.

Holness also was concerned about other words in the bill that had not been defined: encourage, provoke, sexual information, intimidating, tormenting.

“There’s way too much prosecutorial discretion in these terms that are not defined,” Holness said.

Zirkin said the amended version of the bill includes language from other state’s laws, such as Texas, and also avoids language from North Carolina’s cyberbullying law, which was struck down by that state’s Supreme Court in 2016.

Del. Jazz M. Lewis (D-Prince George’s) asked if the 2019 measure also avoids all concerns about constitutionality raised in an advice letter from the Office of the Attorney General last year.

Zirkin said the bill addresses as many concerns as he and other sponsors agreed with.

“This is not going to satisfy everyone’s constitutional concerns,” Zirkin said. “… If we’ve overstepped our bounds in any part of this, then we’ll find out when the Court of Appeals says so.”

Until then, lawmakers could save lives by passing the bill this year, the bill’s sponsors said.

“This is about children getting hurt,” Cardin said. “… And we can stop it if we can just move our laws with technology.”

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution