Frank DeFilippo: The Late Jack Eldridge Wrote the Laws Maryland Lives By

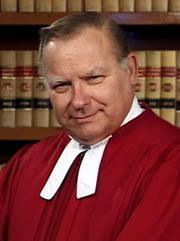

Death is breaking up that old gang of ours. When John C. Eldridge died a couple of weeks ago, the obit writers focused more on his long-term judgeship on the Maryland Court of Appeals than on the mountain of legislation he drafted as Gov. Marvin Mandel’s chief legislative officer. They survive today as the laws and the government we live by.

The times demanded change. The year was 1969 and the intersection of the anti-Vietnam War upheaval and the civil rights movement set the calamitous tone of the era. The cautionary two terms of Gov. Millard J. Tawes (D) (1959-67) and the abbreviated do-little service of Gov. Spiro T. Agnew (R) (1967-69) had left Maryland a blank slate with opportunity begging to be filled in.

One by one, and two by two, they came, the erudite and the lettered, from the Brookings Institution and the Johns Hopkins University, and other venerable centers of the universe, and even the renowned New Deal economist, Robert Nathan, from Montgomery County, to offer their years and their wisdom on how to advance enlightened public policy in Maryland.

Those conversations produced three Ph.D.-economists from Brookings and Hopkins who became the nation’s first state-level Council of Economic Advisers. One, Louis Stetler, eventually became the state’s budget director and, later, an economic adviser to foreign governments.

Eldridge was among those who saw in Mandel’s improvised ascendency to the governorship an opportunity to join in taking a backwater state by the scruff of the neck and yanking it, kicking and screaming, into what was then the 20th Century. Eldridge helped to write the legislative history of the era as well as the state’s laws. He also calculated it as an escalator to a berobed seat on the state’s highest court.

On loan to Mandel, at first, from a law firm he’d just joined, Eldridge decided to make writing laws a full-time job, with his sights set eventually on the Court of Appeals. To fill in the space between the existential now and the futuristic then, Eldridge headed Mandel’s legal team that not only drafted legislation but guided it through the General Assembly, keeping an annual scorecard with very few losses. Eldridge could be haughty and difficult, but his ability was never in doubt.

Eldridge was once told that Mandel remarked often that he had an uncanny skill for drafting legislation that was a rare talent. And Eldridge responded in kind: “I always put a ‘hook’ in each bill and Marvin always found it.”

Scrambling to assemble a government

Eldridge was part of Mandel’s scramble to assemble a government, one that would eventually fit into the flow-chart boxes of the consolidated government and cabinet system Mandel envisioned. The staff was assembled piecemeal over a couple of months and was as diverse as the state itself and probably among the most accomplished and effective ever to inhabit the State House.

Simply put, the staff got the job done and took pride in doing it. Together, Mandel’s staff was described in a Baltimore Sun story and accompanying group photo as “canny operatives.”

The staff and the initial cabinet appointments reflected Mandel’s pragmatic approach to government and politics – a Machiavellian blend of the lion and the fox, part political, part academic, part patronage and part pre-emption. It was an era, too, before the words “liberal” and “conservative” carried the sharp ideological lineation that they etch today.

On that first day of his governorship, Jan. 6, 1969, Mandel made his initial appointments as he hastily began to piece together a staff that began with four: Grace Donald, his long-time secretary and gatekeeper as House speaker would continue in that role; Maurice Wyatt, a young attorney and scion of a Baltimore political dynasty, as appointments (patronage) secretary; Frank Harris, a railroad engineer and loyalist from the House of Delegates, as legislative liaison; and Frank DeFilippo, a long-time Baltimore political and State House reporter for The News American, with a stint at the White House, as press secretary and speechwriter.

Joining the next day was Joseph Anastasi, a real estate developer and activist with the statewide Jaycees from Montgomery County, as administrative officer. And soon after came Ronald Schrieber, a Baltimore attorney who’d worked in the legislative reference department. Wyatt and Anastasi had worked with Mandel in the Humphrey campaign. Soon, Michael Silver, another lawyer, signed on as Wyatt’s deputy in the patronage shop.

From Capitol Hill came Edmond C. Rovner, a jolly genius and a lawyer with years of labor and legislative experience. And from Harvard and the Justice Department came Eldridge, as chief legislative officer, whom Mandel later appointed to the Maryland Court of Appeals. As Eldridge’s deputy, Mandel named Alan M. Wilner, attorney and later an appellate judge on two state high courts after he succeeded Eldridge in the top legislative job. Joining the staff as Rovner’s deputy was Ernie Honig-Kent, an expert on the state Constitution, the structure of government and redistricting for which she became known as “zee map lady.” Rovner and Honing would oversee Mandel’s sweeping reorganization of government, and Eldridge drafted the legislation to accomplish it.

There were others: Hans Mayer, MBA and banker who later became secretary of economic development and, after that, head of MEDCO; Paul Weinstein, Ph.D., an economist and expert on labor relations from the University of Maryland; Gerard Devlin, Ph.D., LL.D. Stanley Fine, another lawyer, joined Eldridge’s staff and later was appointed director of the Maryland Lottery.

They were followed into Eldridge’s suite of offices by other lawyers, Thomas Peddicord, now secretary to the Baltimore County Council, and Joseph Touhy, from the Anne Arundel County state’s attorney’s office. Gail Moran signed up for the Washington office and Fred Spigler came aboard to handle education issues.

As time passed, the staff grew. Thomas L. Burden, also of The News American’s State House bureau was plucked from the State House press room to be deputy press secretary, and later succeeded to the top job as press secretary. Initially, the disparate staff did not like each other very much, but had one thing in common – they all liked Marvin Mandel. (Apologies to those former colleagues whose names are lost in the fog and cobwebs of long ago.)

A shrewd political match

In a stroke that showed Mandel at peak form, the pipe-puffing Jewish governor from the ghetto wards of Baltimore persuaded an authentic WASP, state Sen. Blair Lee III – whose bloodlines include the Lees of Virginia and the Blairs of Blair House – to become his secretary of State, a largely ceremonial post, with the promise to adopt Lee as lieutenant governor when and if the post was created by the voters on referendum, which Mandel intended to propose in the 1970 election, virtually assuring Lee a prime position to be his successor. The constitutional amendment creating the post was written by Eldridge.

The appointment of Lee built a political bridge to an area of the state – the populous, wealthy and educated suburbs around Washington – where Mandel was virtually unknown and whose clubhouse politics might be unacceptable to the high-salaried professionals and government workers who prided themselves on demanding “good government” from its elected officials.

The choice of Lee gave Mandel campaign roots in a continuum of America history. While Robert E. Lee was leading the confederate army, Montgomery Blair was Lincoln’s postmaster general. The Lee family also contributed Maryland’s first popularly elected senator, nine members of Congress, a World War I hero, a U.S. ambassador and three presidents of the Montgomery County Council.

Lee’s father, Col. E. Brooke Lee, had been a state comptroller, and Lee himself had been a Maryland delegate and senator, the position from which Mandel plucked him. Add to the family bio a couple of signers of the Declaration of Independence, Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Richard Henry Lee. Blair Lee, at the urging of his father, Col. E. Brooke Lee, the supreme boss of Montgomery County politics, said yes. And in one of those toothsome twists that politics often takes, Lee had run against his own father’s machine to win his Senate seat. Wow! What a catch.

Lee and his staff, though separated by a hallway, supplemented Mandel’s. Lee did much of the preliminary work on the budget and on education issues. Thomas Downs, Lee’s staff lawyer, was responsible for environmental issues, and Shep Abell, attorney and progeny of the family that owned a big chunk of The Baltimore Sun, worked on intergovernmental issues.

Mandel was a transition governor who reorganized and modernized the three branches of Maryland government – the General Assembly, as speaker of the House of Delegates, and the executive and judicial branches as governor, the last two with Eldridge as the laws’ draftsman and his legal team as their vote-counters and elbow-grabbers.

Mandel was neither as liberal as his record belies, nor as conservative as he appeared to be in old age. He was the consummate pragmatist who sensed what the times demanded and what politically should be done for applause and electoral survival, and he did it, whether he believed in it or not. And Eldridge was at his side, ready to write the legislation that accomplished it all. RIP Jack Eldridge.

“Bless the days that saw us young and years that made us wise.” – Julia Ward Howe.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution