Frank DeFilippo: Religion and Politics Are a Toxic Mix

God is dead. Well, almost.

We know that God is on life support because recent polls say so. He, She or it has been around a long time, always, theologians say. But the number of people who believe that is rapidly diminishing. The departure from theological orthodoxy is occurring at the intersection of religion, science and politics, say those who’ve fled the flock. That, in a word, is why subscribing to God and religion is called faith.

Frank A. DeFilippo

But wait! God is about to get a wake-up call. It’ll come in the U.S. Senate, not exactly a reliquary of sainthood, when Judge Brett Kavanaugh appears for confirmation hearings to the Supreme Court. Kavanaugh’s Roman Catholicism, and the weight of the Catholic Church on the Supreme Court, along with his views – past, present and future – on the Rorschach-test of Roe vs. Wade, will be enough to give God heartburn. So packed with Catholics is the Supreme Court that soon it’ll be telling the Vatican what to do.

But the war of words over Roe vs. Wade may be largely symbolic, but nonetheless in defense of a strongly held principle. The introduction of new pharmaceuticals such as the morning-after pill has made chemically induced abortions as available as the nearest drug store.

This election cycle has witnessed lots of attention to God and religion. First, we have that exemplar, President Trump, accused of sexual misbehavior by a dozen women and thrice married, and his casual reference to “crackers” and wine at Methodist services. Trump and five others – James Polk, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, William McKinley and George W. Bush – have been Methodists.

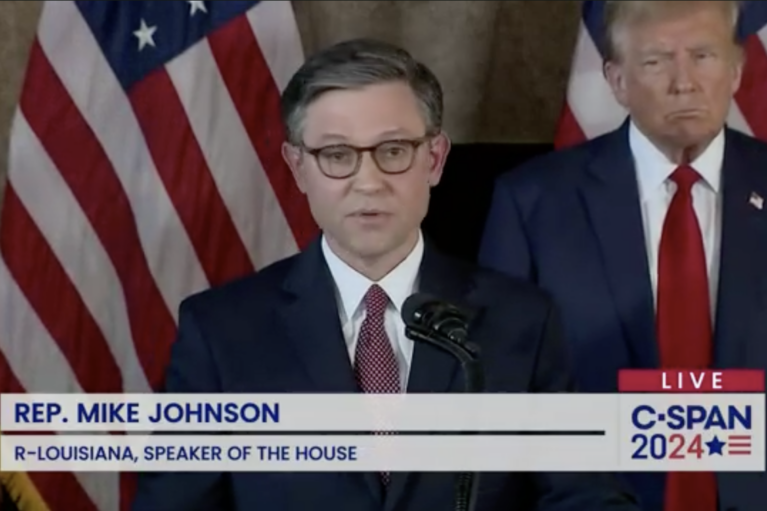

But foremost among the religionists is Trump’s bobblehead and avenging archangel, Vice President Mike Pence, a collapsed Catholic and the administration’s ambassador to the evangelical wing of the Republican Party, who calls himself a “Christian” before anything else. It is Pence’s assignment to keep the fundamentalist Republican base in line while he sharpens the dagger at Trump’s back.

Pence is the man who would be president if anything legal, or otherwise human, befalls Trump. And he’s beginning to let his ambition show by not first getting permission slips to go it alone and by failing to conceal his open-faced glee over the shimmering prospect of becoming president.

There have been previous occasions when religion was front-and-center as an ink-blot test of acceptability for political office and an exaggeration of stereotypical bugaboos. Mitt Romney’s Mormonism was viewed by many as outside mainstream Protestantism primarily because of its perceived views on matrimony and secret rituals. And President Obama was considered a Kenyan socialist who consorted with a proponent of the radical Black Liberation Theology, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright. John F. Kennedy had to convince Protestant ministers that he wouldn’t take orders from the Vatican if he was elected president.

And on another point of departure, God and religion have, or has, had little mention or played no measurable role on the Democratic side of the eternal divide as compared to its significance in the Republican Party’s shotgun marriage to the right flank of American politics. Yes, the rules of engagement for the two parties differ in kind and degree. And yes, again, there is an extreme branch of Catholicism that aligns with evangelicals. (Amy Coney Barrett, a Catholic who was short-listed for the Supreme Court, is a member of “People of Praise,” an obscure, charismatic faith group.)

One recent accounting found nonbelievers to be more liberal than conservative. The General Social Survey, conducted in tandem by two universities, revealed that 40 percent of those who’ve abandoned religion identified themselves as liberal while only 9 percent called themselves conservative.

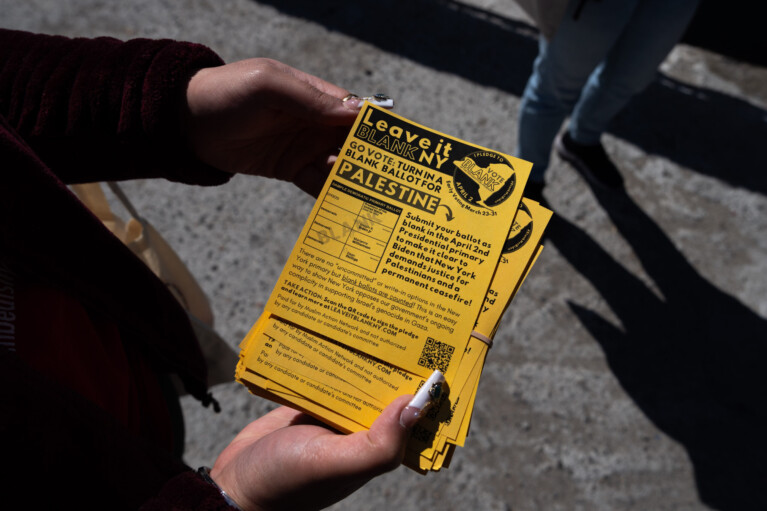

But the so-called evangelical vote, considered so significant in GOP primary elections, had all but evanesced, and it manifests itself as vaguely a whisper except at occasional prayer breakfasts, until muster is called for the Kavanaugh crusade in the Senate. They are salivating like Pavlov’s puppy over the chance to rid America of abortion, abetted by Trump who chose Kavanaugh for pretty much that reason. (In Maryland, women’s reproductive rights are protected by state law no matter who’s on the Supreme Court or what the court does.)

God and religion have reentered politics in other ways, too, with Kavanaugh as Trump’s standard bearer to: (1) Establish religious freedom by fiat (essentially repeal the First Amendment), and (2) repeal the Johnson Amendment, which prohibits churches from engaging in partisan political activity or lose their tax-exempt status. Surely God jests.

For the most part, Americans brush aside such narrow and quixotic arguments. All but the most zealous subscribe directly to the teaching of Christ on the issue of separation of church and state: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” (Mark 12:17). In other words, the two are a toxic mix and, in most cases, should butt out of each other’s business.

Americans, and many other democracies, have made peace with the notion of church-state separation. It’s called pluralism. Government and religion operate on parallel tracks and rarely meet – one with a higher paycheck, the other with a higher authority (no, not President Trump). But there are those, of course, who believe that America is God’s masterwork because the name is inscribed on our currency and included in the Pledge of Allegiance – two afterthoughts that were championed by President Eisenhower in the 1950s.

A while back, Pew Research Center survey numbers advanced the idea of a church-state firewall in a forceful and dramatic way. They said that America is going to hell in a handcart, if such a thing as a theological hell exists. A quarter of the nation’s 310 million people now have no affiliation with any religion, and half the Americans who have left their churches for whatever reason, say they no longer believe in God.

To some extent, those spiritual drop-outs can be attributed, at least in part, to the modern presentation and perception of religion itself and what the three major religions have allowed themselves to become: Christianity as a magic show, Judaism as a food festival and Islam, at the risk of precipitating another Charlie Hebdo event, an eternal erotic experience.

The earlier Pew research revealed that about a quarter of those surveyed said they no longer subscribe to organized religion and nearly half said they just “don’t believe.” Plumbing deeper for reasons of those who gave up on God and religion, Pew found “science,” lack of “belief in miracles,” “common sense,” and “lack of evidence” as intellectual hat-racks. Others said, simply, that they “do not believe in God.”

Yet religion as an institution persists in convincing numbers. Another Pew flow-chart reveals religion embedded in percentages of the U.S. population. First, Christian: Evangelical Protestant, 25.4 percent; Mainline Protestant, 14.7 percent; historically black Protestant, 6.5 percent; Catholic, 20.8 percent; and Mormon, 1.6 percent. Non-Christian: Jewish, 1.9 percent; Muslim, 0.9 percent; Buddhist, 0.7 percent. Other: Atheist, 3.1 percent; Agnostic, 4.0 percent, and nothing in particular, 15.8 percent.

The five largest denominations, according to the National Council of Churches, are: Catholic, 68.2 million members; Southern Baptist Convention, 16.1 million; United Methodist Church, 7.6 million; Church of the Latter Day Saints (Mormon), 6.1 million; and Church of God in Christ, 5.4 million.

Millennials find religious institutions especially unappealing. They appear motivated more by the social gospels, or good works, as taught by Christ, than in doctrinaire teachings as proclaimed by churches. The God of their parents as a bearded and vengeful old crank who commands constant worship and adulation does not exist in their pantheon of expression but only as a trope in the Old Testament.

And as many religionists, especially fundamentalists, often dismiss the foibles of man as the will of God, young people are more inclined to place the blame squarely where it belongs – to those here on earth, in a kind of scornful pantheism. Yet despite their good intentions, whatever the motivation, millennials remain blissed out on politics. One survey showed young people in Nevada preferred voting for legalization of weed, vs. choosing a president.

Religious distinctions appear to be a major relevance in this election cycle, especially through the timing of Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings and as a prop to the wholly Trump coalition that he painstakingly works to reinforce but not expand.

As for the role of the Almighty in this or any other election, God pays no attention to petitions but in justice and mercy favors the candidates with the best get-out-the-vote operations.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution