Frank DeFilippo: Redistricting Reform Could Make a Bad System Worse

Redistricting is legalized body-snatching. Everybody knows it. Everyone does it. Former Gov. Martin O’Malley (D) admitted the ruse in a deposition. Implicit in Republican Gov. Larry Hogan’s caterwauling about a non-partisan commission to oversee redistricting is the likelihood that his party would gain congressional seats. Maryland’s congressional map resembles a run-away ink blot. So do the maps of 26 states where Republicans control the governorships and legislatures. Even the Supreme Court seems inclined, at least momentarily, to wink at the deception as it has in the past.

Redistricting has always been an inconvenience, if not a bafflement. Back in 1962, Maryland was awarded an eighth member of Congress as directed by population growth. The Democratic ministers of influence were so flummoxed by the prospect of having to jigger the map and shuffle bodies that they whiffed by creating the extraordinary office of congressman at-large.

Heretofore unheard of, at least in these parts, the congressman at-large ran statewide and had the same broad constituency as a U.S. senator, but without the portfolio or perks of the office. The congressman at-large represented everyone but no one. That year, Carlton R. Sickles, a state delegate from Prince George’s County, won the job. He served four years (two terms) before the office was regularized and absorbed into the congressional map as the 8th District, and, after many mutations, Western Maryland became the 6th District, the barren westerly territory that is now in dispute.

In the mid-1960s, the General Assembly was forced to design an eighth congressional district. But such a Rube Goldberg construction did not come with how-to instructions. Then, as now, the suburbs around Baltimore and the District of Columbia were rapidly gaining population while Baltimore city and the Eastern Shore were losing in the body count. But the city insisted on retaining the three congressman it had always had in addition to its full representation in the General Assembly, which involved legislative reapportionment.

At a point in the debate, punches were almost thrown. The bibulous Sen. Frederick Malkus (D) of Cambridge on the Eastern Shore accused House Speaker Marvin Mandel (D) of Baltimore of acting out of purely narrow, selfish interests. All Mandel’s doing “is trying to protect the Jews in Baltimore,” Malkus intoned. Informed of Malkus’ incendiary remark, Mandel, a college flyweight boxer though no match in height or weight to Malkus, marched off the speaker’s rostrum and over to the Senate where he threatened to pummel the offending Eastern Shoreman. A few angry words and awkward moments, but no fight, occurred as tempers cooled.

More recently, following the 2000 census, Gov. Parris Glendening (D) used the legislative reapportionment maps to punish errant legislators and political enemies. Under the law, if redrawn maps stray too far off kilter, the Maryland Court of Appeals will step in and edit them to its satisfaction. Which is what happened when Glendening tried to reapportion several recalcitrant lawmakers from the east side of Baltimore County, and a few others, out of office. (The Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently redrew congressional maps that were skewed heavily in favor of Republicans.)

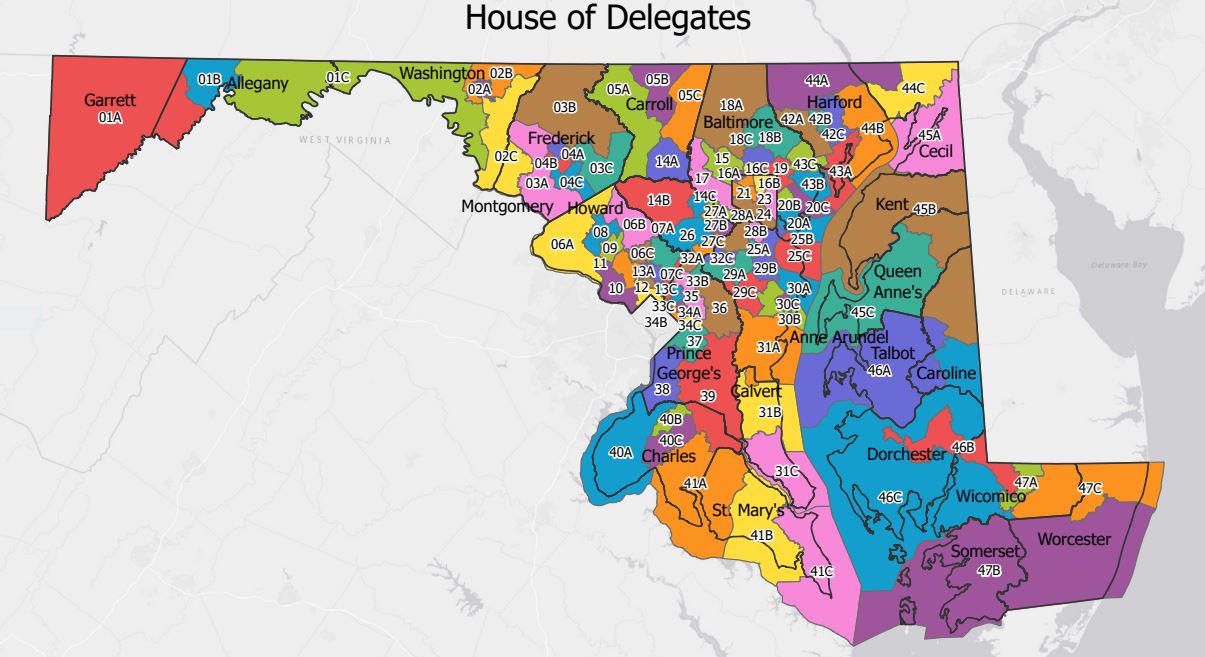

Many states come in neat, compact geometrical packages of squares and rectangles. But Maryland is a weirdly misshapen jigsaw of odd angles and jagged edges with a large flush of water separating its eastern shore and western mainland. Most of the state’s population is clustered in five jurisdictions along I-95, the burgeoning backbone of the 2-1 majority Democratic party.

The rest is geography. Because people choose where to live doesn’t mean they’re misplaced. To subdivide the state fairly and evenly is nearly impossible because of its Picasso-esque shape; for the Supreme Court to try it might be considered an invasive act, which is why the court has always been reluctant to take politics out of politics.

Here’s the problem, as well as a tutorial for those new to the arcane subject of redistricting.

The size of the House of Representatives is fixed by law at 435 members. Representation is based on population. At the conclusion of each decennial census, state representation is shifted and awarded according to population loss or gain. But the membership number never changes. The real problem is developing in the U.S. Senate, whose membership is based on geography, with each state having two members. The coastal states are bulging as the nation’s new population centers while the so-called flyover states remain static or have decreasing populations.

For example, California has 39 million people, Wyoming has 585,000. Both have two senators and equal say on all voting matters in the Senate.

Redistricting is about bodies in motion. Drawing legislative boundaries to accommodate Maryland’s six million people of all colors, socio-economic classes, geographic distribution and competing political parties is no easy assignment, even in the age of algorithms. Redistricting and its local twin, reapportionment, is like re-shaping a balloon – squeeze one place and it bulges in another. It’s a tetchy and vengeful business. A few squiggles on the map here, or the shift of a couple of precincts there, can make or break a political career. At its most cynical, redistricting can pit incumbent against incumbent with the surety that one must go.

Congressional redistricting has only two guidelines – population balance and protection of minority representation. Legislative reapportionment, however, also considers contiguity, commonality of interests as well as population balance. Following the 2020 census, there are expected be about 750,000 people in each of Maryland’s eight congressional districts, based on the state’s current population of a tad over six million.

The issue that was argued before the Supreme Court in the Maryland case turned on a fulcrum of First Amendment rights. The 6th District was so bastardized, admittedly so by O’Malley, that Republicans in the district were denied the right to express a choice for Congress. Hundreds of thousands of voters were shifted deliberately to enhance Democrats’ chances of picking up an additional seat by making it impossible for the incumbent Republican, Roscoe Bartlett, to win. The Maryland case was linked to gerrymander cases from Wisconsin and North Carolina.

Whoever is elected governor of Maryland in November – Hogan or one of seven Democrats – will inherit the assignment of redrawing the state’s maps following the 2020 census. The Supreme Court left unclear whether, or when, it will rule, so the next governor can thank or blame the court. There’s no easy prescription.

Hogan has repeatedly called for legislation that would create a non-partisan commission to draw district maps. But Democrats have maintained that they would support the idea only if every other state adopts the same approach which, practically, is the only way it would work. Republicans have the most to lose overall if the Supreme Court decides to end gerrymandering, which has dictated the rules of political engagement for nearly 200 years, since 1812, when Gov. Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts employed the sleight-of-hand to empower his Democratic-Republican Party.

Today’s methods of grabbing and maintaining power are just as blatant but more sophisticated, carried out with surgical precision with computers and encouraged by how the two major political parties have evolved, mainly along racial lines.

The two words often associated with redistricting are “cracking” and “packing” – in one case breaking up and scattering concentrations of votes, and in the other, lumping together similar voters. The most obvious application is the bleaching of districts to create predominately white and black warrens. This has been achieved, in many cases, with the winking connivance of black leaders to assure safe black seats (at the same time they guarantee unchallenged white seats.)

Be wary of any hope for redistricting reform. It could make a bad system even worse because there is no easy formulaic solution. And be especially wary of this Supreme Court, which is more political than most, and more sensitive to the elected officials who nominate and approve federal judicial appointments along ideological lines.

Creative Commons Attribution

Creative Commons Attribution